Có những người không nói ra phù hợp với những gì họ nghĩ và không làm theo như những gì họ nói. Vì thế, họ khiến cho người khác phải nói những lời không nên nói và phải làm những điều không nên làm với họ. (There are people who don't say according to what they thought and don't do according to what they say. Beccause of that, they make others have to say what should not be said and do what should not be done to them.)Rộng Mở Tâm Hồn

Để có thể hành động tích cực, chúng ta cần phát triển một quan điểm tích cực. (In order to carry a positive action we must develop here a positive vision.)Đức Đạt-lai Lạt-ma XIV

Phán đoán chính xác có được từ kinh nghiệm, nhưng kinh nghiệm thường có được từ phán đoán sai lầm. (Good judgment comes from experience, and often experience comes from bad judgment. )Rita Mae Brown

Nay vui, đời sau vui, làm phước, hai đời vui.Kinh Pháp Cú (Kệ số 16)

Ngủ dậy muộn là hoang phí một ngày;tuổi trẻ không nỗ lực học tập là hoang phí một đời.Sưu tầm

Nhẫn nhục có nhiều sức mạnh vì chẳng mang lòng hung dữ, lại thêm được an lành, khỏe mạnh.Kinh Bốn mươi hai chương

Lấy sự nghe biết nhiều, luyến mến nơi đạo, ắt khó mà hiểu đạo. Bền chí phụng sự theo đạo thì mới hiểu thấu đạo rất sâu rộng.Kinh Bốn mươi hai chương

Nghệ thuật sống chân chính là ý thức được giá trị quý báu của đời sống trong từng khoảnh khắc tươi đẹp của cuộc đời.Tủ sách Rộng Mở Tâm Hồn

Hành động thiếu tri thức là nguy hiểm, tri thức mà không hành động là vô ích. (Action without knowledge is dangerous, knowledge without action is useless. )Walter Evert Myer

Chúng ta thay đổi cuộc đời này từ việc thay đổi trái tim mình. (You change your life by changing your heart.)Max Lucado

Hầu hết mọi người đều cho rằng sự thông minh tạo nên một nhà khoa học lớn. Nhưng họ đã lầm, chính nhân cách mới làm nên điều đó. (Most people say that it is the intellect which makes a great scientist. They are wrong: it is character.)Albert Einstein

Trang chủ »» Danh mục »» TỦ SÁCH RỘNG MỞ TÂM HỒN »» none »» The Birth of an American Form of Buddhism: The Japanese-American Buddhist Experience in World War II »»

none

»» The Birth of an American Form of Buddhism: The Japanese-American Buddhist Experience in World War II

Xem Mục lục

Xem Mục lục  Vietnamese || Đối chiếu song ngữ

Vietnamese || Đối chiếu song ngữ

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- The Path of Peace: A Journey of Healing Across America

- none

- none

- none

- none

- He Walks Like Christ, He Walks with the Buddha

- none

- The Rules Don't Shiver

- Will you be my dad until I die?

- none

- none

- The Old Man at the Thrift Store

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- More Than Half a Century of the World Buddhist Sangha Council

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- Equity in Existence and Mortality (Life and Death)

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- The Buddhist Just Society

- The Buddhist Just Society

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- The Broken Gong

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- How to Do Metta

- none

- none

- none

- Six Ways to Boost Blood Flow

- none

- none

- none

- Thich Nhat Hanh’s Love Letter to the Earth

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- Introduction: The Central Place of the Ideas of Karma and Rebirth in Buddhist Thought

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- Chapter 25: Human Rights

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- Dear beloved Thay

- Dear beloved Thay

- none

- Bāhiya's Teaching: In the Seen is just the Seen

- Bāhiya's Teaching: In the Seen is just the Seen

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- Buddha on Politics, Economics, and Statecraft

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- Tonglen on the Spot

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- War, Violence, Hatred, Non-violence, and Compassion.

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- Vasubandhu

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- Volodymyr Zelensky’s inaugural address

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- The Cat Who Went To Heaven

- none

- none

- none

- Speech by Dr. Carola Roloff

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- Practical Vipassana Meditation Excercises by Mahasi Sayadaw

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- The Art of Living

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- BIOGRAPHY OF THE MOST VENERABLE BHIKSUNI THÍCH NỮ DIỆU TÂM

- none

- PIANO SONATA 14

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- The Hermit Who Owned His Mountain

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- A story about Nagarjuna

- none

- none

- none

- none

- Dhamma Talk of Master Thich Nhu Dien

- none

- none

- Magical Emanations: The Unexpected Lives of Western Tulkus

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- Introduction to the selections from Vajrayāna Buddhism

- Introduction to the selections from Mahāyāna Buddhism

- Introduction to the selections from Theravāda Buddhism

- Introduction to the Sangha, or community of disciples

- Introduction on the life of the historical Buddha

- INTRODUCTION

- none

- none

- Dharma Talk at Beel Low See Temple, Singapore

- none

- none

- Buddhist Perspectives on Contemporary Issues

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- How Lankan Buddhists won the battle against proselytization

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- Managing Emotions Effectively in Uncertain Times

- What Happens After Coronavirus?

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- The Thirty-Seven Practices of All the Bodhisattvas

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- Invitation to Presencing for Each Other 6

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- The Desert Willow

- none

- Antonio and His Treasure

- none

- Tim and Grandpa Joe

- none

- none

- none

- Amrita and the Elephants

- Egbert and the Fisherman

- The Spirit of the Tree

- Danan and the Serpent

- none

- none

- The Beautiful White Horse

- none

- none

- none

- The Monkey Thieves

- Angelica and King Frederick

- Aloka and the Band of Robbers

- none

- The Shiny Red Train

- The Sheep Stealers

- none

- Ester and Lucky

- The new girl

- none

- The Enlightenment of Chiyono

- The Magic Moonlight Tree

- none

- none

- none

- Bella and the Magic Soup

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- The Man-made Obstacle Distinguishing between problems of human birth and problems of human making

- none

- none

- How to Practice Chanting

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- Marx and Walking Zen

- none

- none

- The Math Koan

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- Phổ Môn Kệ Tụng

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- How Buddhists Can Benefit from Western Philosophy

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- »» The Birth of an American Form of Buddhism: The Japanese-American Buddhist Experience in World War II

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- The Flood of Tears

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- Can our brains see the fourth dimension?

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- Our dedication

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- Peace in each breath is peace in life Practice breathing for good sleep and peace in life.

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- The Price of a Miracle

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- Reminiscing Elder Brother Cao Chanh Huu

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- Everything is Changeable

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- 太上感應篇(第一集)新加坡淨宗學會

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- A Devoted Son

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- The Art of Living: Vipassana Meditation

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- “Returning Home” a Dharma retreat for the Youth in America

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- TET, a Vietnamese Tradition

- Wake Up - The Awakening from Within

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- How a Hollywood Mogul Found True Happiness

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- Lonely Journey of Thousand Miles

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- Discourse on Loving Kindness (Metta Sutra)

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- Ambrosia Rain – The Merit of Life-Release

- Place Holder of Thousands of Stars

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- Your Light May Go Out

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- The Ultimate Happiness

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- Dalai Lama: 5 things to keep in mind for the next four years

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- Buddhism scripture teachers struggling to keep up with demand from state schools

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- LETTER TO THỪA THIÊN - HUẾ'S BUDDHIST STUDENTS

- Why Larung Gar, the Buddhist institute in eastern Tibet, is important

- none

- none

- Buddhism and the Youth

- Five Precepts

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

- none

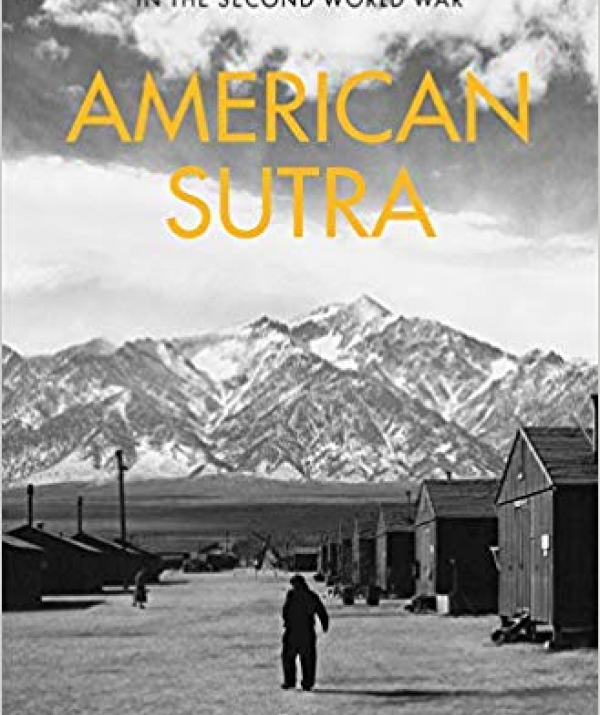

For many, the story of Buddhism in America begins with the Beat poets of the 1950s or the hippies of the 1960s and 1970s. In fact, Buddhism first landed on American soil at least a century earlier with the arrival of Asian immigrants from across the Pacific. In 1893, the first Jodo Shinshu priests arrived in San Francisco, establishing what would become the Buddhist Churches of America. And, according to scholar and author Duncan Ryuken Williams, it was in the experiences of Jodo Shinshu and other Japanese Buddhists in the Second World War that a uniquely American Buddhism was formed.

This began in the wake of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on 7 December 1941, when the American identity of Japanese Americans, particularly those of a Buddhist background, was called into question.

Just over two months later on 19 February 1942, in the American rush to war, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, which authorized the incarceration of as many as 120,000 Americans of Japanese descent.

In his new book American Sutra: A Story of Faith and Freedom in the Second World War (Harvard University Press 2019), Duncan Ryuken Williams, professor of Religion and East Asian Languages & Cultures and director of the USC Shinso Ito Center for Japanese Religions and Culture, retells the stories of Japanese Americans during World War II, with a particular focus on the role Buddhism played. He examines what it meant to be American and Buddhist for Japanese Americans in an era of war, and renewed racism and xenophobia.

As Janis Hirohama writes:

The entire Japanese American community suffered during the war, but as American Sutra shows, Buddhists were particularly targeted. U.S. government and military authorities viewed Buddhism as un-American and its followers as more likely to be disloyal. Most Buddhist priests were swiftly arrested and detained after Pearl Harbor, and severe restrictions were placed on the practice of Buddhism in both Hawaii and the mainland. (The North American Post)

The concern about the Japanese practice of Buddhism fit into an ongoing fear of non-Christian religions in American history, “from widespread suspicion of the so-called ‘heathen Chinee’ [a phrase popularized by American writer Bret Harte in an unsuccessful effort to satirize anti-Chinese sentiment of the time] in the late 19th century, to dire warnings of a ‘Hindoo peril’ early in the 20th century, to rampant Islamophobia in the present century. Even before war with Japan was declared, Buddhists encountered similar mistrust.” (Smithsonian.com)

Williams writes of the experience of Japanese American Buddhists in Hawaii:

The early roundup of the Buddhist leadership, whether citizen or not, was a harbinger of a broader persecution of non-Christian religions on the Hawaiian Islands. Under martial law, the misguided presumption that Japanese American Christians were necessarily more loyal to the United States became increasingly apparent, and the historical animus against Buddhism and Shinto intensified.

Thus, during the first several years of the war, Buddhists and Shintoists were restricted from practicing their religion, and had to petition the Army’s G-2 intelligence division for permission, most often denied, to meet at their temples and shrines. Several Shinto shrines, such as the Izumo Taisha shrine in Honolulu, were simply confiscated and declared “gifts” to the city and county of Honolulu. On the island of Kauai, the Military Governor’s Office coordinated the closure of the island’s Japanese-language schools with the dissolution of Buddhist temples. Ultimately, 13 of the island’s 19 Buddhist temples were eliminated. (American Sutra: A Story of Faith and Freedom in the Second World War)

Life in the camps was difficult. Many of those interned were given just hours to leave their homes with only the possessions they could carry on their backs. Nonetheless, Japanese-American Buddhists worked to preserve their religious identities and practices.

“Prisoners at the Fort Lincoln, North Dakota, internment camp celebrated Hanamatsuri [the Japanese celebration of the Buddha’s birthday] by pouring sweetened coffee over a baby Buddha statue carved from a carrot. Young American-born Buddhists became leaders in the camps, with YBAs organizing social activities and religious gatherings that helped revitalize their sanghas.” (The North American Post)

“The Buddha taught that identity is neither permanent nor disconnected from the realities of other identities,” Williams writes in American Sutra. “From this vantage point, America is a nation that is always dynamically evolving—a nation of becoming, its composition and character constantly transformed by migrations from many corners of the world, its promise made manifest not by an assertion of a singular or supremacist racial and religious identity, but by the recognition of the interconnected realities of a complex of peoples, cultures, and religions that enrich everyone.”

And thus in the shadow of war and racism in a “Christian nation,” Williams suggests that Japanese-American Buddhists created American Buddhism. It was in one of the camps, Utah’s Topaz War Relocation Center, that the Buddhist Missions of North America was renamed Buddhist Churches of America. Other innovations from the time included the singing of gathas (Buddhist poems or songs), standardized English-language service books, and the adoption of Sunday schools.

These and other changes during and after the war, Williams suggests, gave birth to a Buddhism with a uniquely American identity. He shows how the adversity of their experiences strengthened their Buddhist faith and the Japanese-American Buddhists “to assert their right to define themselves as equally Buddhist and American, and created a truly American form of Buddhism.” (North American Post)

Williams recounts in the book the stories of numerous lives rocked by a time of extreme change, and in those stories are found a blend of Buddhist wisdom and American experience: “The long-ignored stories of Japanese Buddhists attempting to build a free America—not a Christian nation, but one of religious freedom—do not contain final answers, but they do teach us something about the dynamics of becoming: what it means to become American—and Buddhist—as part of an interconnected and dynamically shifting world.”

The book, released on 19 February, has been met with widespread acclaim as Williams has embarked on a national speaking tour. The release date is significant as it is the Day of Remembrance, which commemorates the incarceration of Japanese Americans in World War II.

MUA THỈNH KINH SÁCH PHẬT HỌC

DO NXB LIÊN PHẬT HỘI PHÁT HÀNH

Mua sách qua Amazon sẽ được gửi đến tận nhà - trên toàn nước Mỹ, Canada, Âu châu và Úc châu.

Quý vị đang truy cập từ IP 216.73.216.157 và chưa ghi danh hoặc đăng nhập trên máy tính này. Nếu là thành viên, quý vị chỉ cần đăng nhập một lần duy nhất trên thiết bị truy cập, bằng email và mật khẩu đã chọn.

Chúng tôi khuyến khích việc ghi danh thành viên ,để thuận tiện trong việc chia sẻ thông tin, chia sẻ kinh nghiệm sống giữa các thành viên, đồng thời quý vị cũng sẽ nhận được sự hỗ trợ kỹ thuật từ Ban Quản Trị trong quá trình sử dụng website này.

Việc ghi danh là hoàn toàn miễn phí và tự nguyện.

Ghi danh hoặc đăng nhập

... ...

Trang chủ

Trang chủ