Người ngu nghĩ mình ngu, nhờ vậy thành có trí. Người ngu tưởng có trí, thật xứng gọi chí ngu.Kinh Pháp cú (Kệ số 63)

Hành động thiếu tri thức là nguy hiểm, tri thức mà không hành động là vô ích. (Action without knowledge is dangerous, knowledge without action is useless. )Walter Evert Myer

Người cầu đạo ví như kẻ mặc áo bằng cỏ khô, khi lửa đến gần phải lo tránh. Người học đạo thấy sự tham dục phải lo tránh xa.Kinh Bốn mươi hai chương

Người biết xấu hổ thì mới làm được điều lành. Kẻ không biết xấu hổ chẳng khác chi loài cầm thú.Kinh Lời dạy cuối cùng

Cơ học lượng tử cho biết rằng không một đối tượng quan sát nào không chịu ảnh hưởng bởi người quan sát. Từ góc độ khoa học, điều này hàm chứa một tri kiến lớn lao và có tác động mạnh mẽ. Nó có nghĩa là mỗi người luôn nhận thức một chân lý khác biệt, bởi mỗi người tự tạo ra những gì họ nhận thức. (Quantum physics tells us that nothing that is observed is unaffected by the observer. That statement, from science, holds an enormous and powerful insight. It means that everyone sees a different truth, because everyone is creating what they see.)Neale Donald Walsch

Nếu không yêu thương chính mình, bạn không thể yêu thương người khác. Nếu bạn không có từ bi đối với mình, bạn không thể phát triển lòng từ bi đối với người khác.Đức Đạt-lai Lạt-ma XIV

Khi bạn dấn thân hoàn thiện các nhu cầu của tha nhân, các nhu cầu của bạn cũng được hoàn thiện như một hệ quả.Đức Đạt-lai Lạt-ma XIV

Rời bỏ uế trược, khéo nghiêm trì giới luật, sống khắc kỷ và chân thật, người như thế mới xứng đáng mặc áo cà-sa.Kinh Pháp cú (Kệ số 10)

Ai sống một trăm năm, lười nhác không tinh tấn, tốt hơn sống một ngày, tinh tấn tận sức mình.Kinh Pháp cú (Kệ số 112)

Sự giúp đỡ tốt nhất bạn có thể mang đến cho người khác là nâng đỡ tinh thần của họ. (The best kind of help you can give another person is to uplift their spirit.)Rubyanne

Bất lương không phải là tin hay không tin, mà bất lương là khi một người xác nhận rằng họ tin vào một điều mà thực sự họ không hề tin. (Infidelity does not consist in believing, or in disbelieving, it consists in professing to believe what he does not believe.)Thomas Paine

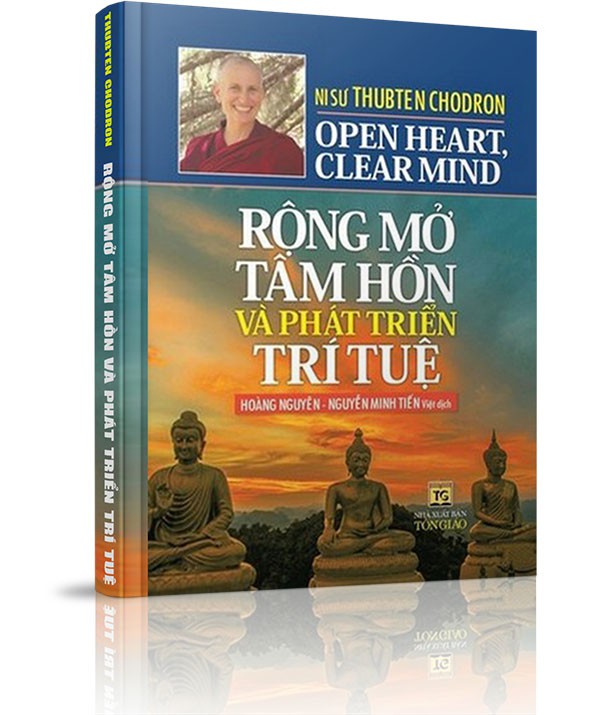

Trang chủ »» Danh mục »» TỦ SÁCH RỘNG MỞ TÂM HỒN »» Open Heart, Clear Mind »» 3. Love vs attachment »»

Open Heart, Clear Mind

»» 3. Love vs attachment

Xem Mục lục

Xem Mục lục  Vietnamese || Đối chiếu song ngữ

Vietnamese || Đối chiếu song ngữ

- Forward (H. H. Dalai Lama)

- Introduction and overview

- Part I: The Buddhist approach

- Part II: Working effectively with emotions. 1. Where is happiness

- 2. Taking the ache out of attachment

- »» 3. Love vs attachment

- 4. Managing anger

- 5. Closed-mindedness

- 6. Accurately viewing ourselves

- 7. From jealousy to joy

- 8. Catching the thief

- 9. The culprit: selfishness

- Part III: Our current situation - 1. Rebirth

- none

- 3. Cyclic existence

- Part IV: Our potential for growth - 1. Buddha nature

- 2. Our precious human life

- Part V: The path to enlightenment - 1. The Four Noble Truths

- 2. The determination to be free

- 3. Ethics

- 4. Nurturing altruism

- 5. Wisdom realizing reality

- 6. Meditation

- 7. Taking refuge

- Part VI: History and traditions - 1. The Buddha’s life and the growth of Buddhism

- 2. A survey of Buddhist traditions today

- Part VII: Compassion in action

- none

All of us would like to have positive feelings for others. We know that love is the root of world peace. What is love and how do we develop it? What is the difference between loving people and being attached to them?

Love is the wish for others to be happy and to have the causes of happiness. Having realistically recognized others’ kindness as well as their faults, love is focused on others’ welfare. We have no ulterior motives to fulfill our self-interest; we love others simply because they exist.

Attachment, on the other hand, exaggerates others’ good qualities and makes us crave to be with them. When we’re with them, we’re happy; when we’re separated, we’re miserable. Attachment is linked with expectations of what others should be or do.

Is love as it is usually understood in our society really love? Before we know people they are strangers, and we feel indifferent towards them. After we meet them they may become dear ones for whom we have strong emotions. Let’s look closer at how people become our friends.

Generally we’re attracted to people either because they have qualities we value or because they help us. If we observe our own thought processes, we’ll notice that we look for specific qualities in others. Some of these are qualities we find attractive, others are those our parents or society value. We examine someone’s looks, education, financial situation and social status. If we value artistic or musical ability, we look for that. If athletic ability is important to us, we check for that. Thus, each of us has different qualities we look for and different standards for evaluating them. If people have the qualities on our “internal checklist” we value them. We think they’re good people who are worthwhile. It appears to us as if they are great people in and of themselves, unrelated to our evaluation of them. But in fact, because we have certain preconceptions about which qualities are desirable and which aren’t, we’re the ones who create the worthwhile people.

In addition, we judge people as worthwhile according to how they relate to us. If they help us, praise us, make us feel secure, listen to what we say and care for us when we’re sick or depressed, we consider them good people. This is very biased, for we judge them only in terms of how they relate to us, as if we were the most important person in the world.

Generally we think that if people help us, they’re good people; while if they harm us, they’re bad people. If people encourage us, they’re wonderful; if they encourage our competitor, they’re obnoxious. It isn’t their quality of encouragement that we value, but the fact that it’s aimed at us. Similarly, if people criticize us, they’re mistaken or inconsiderate. If they criticize someone we don’t like, they’re wise. We don’t object to their trait of criticizing, only its being aimed at us.

The process by which we discriminate people isn’t based on objective criteria. It’s determined by our own preconceptions of what is valuable and how that person relates to us. Underlying this are the assumptions that we’re very important and that if people help us and meet our preconceived ideas of goodness then they’re wonderful in and of themselves.

After we’ve judged certain people to be good, whenever we see them it appears to us as if goodness is coming from them. However, were we more aware, we’d recognize that we have projected this goodness onto them.

If certain people were objectively worthwhile and good, then everyone would see them that way. But someone we like is disliked by another person. This occurs because each of us evaluates others based on our own preconceptions and biases. People aren’t wonderful in and of themselves, independent of our judgment of them.

Having projected goodness onto some people, we form fixed conceptions of who they are and then become attached to them. Some people appear near-perfect to us and we yearn to be with them. Desiring to be with the people who make us feel good, we become emotional yo-yos: when we’re with those people, we’re up; when we’re not, we’re down.

In addition, we form fixed concepts of what our relationships with those people will be and thus have expectations of them. When they don’t live up to our expectations we’re disappointed or angry. We want them to change so that they will match what we think they are. But our projections and expectations come from our own minds, not from the other people. Our problems arise not because others aren’t who we thought they were, but because we mistakenly thought they were something they aren’t.

For example, after Jim and Sue were married for a few years, Jim said, “Sue isn’t the same woman I married. When we got married she was so supportive and interested in me. She’s so different now.” What happened?

First, Sue’s personality isn’t fixed. She’s constantly changing in response to the external environment and her internal thoughts and feelings. It’s unrealistic to expect her to be the same all the time. All of us grow and change, going through highs and lows.

Second, can we ever assume we know who someone else is? When Jim and Sue were getting to know each other before they were married, each one built up a conception of who the other one was. But that conception was only a conception. It wasn’t the other person. Jim’s concept of Sue wasn’t Sue. However, because Jim wasn’t aware of this, he was surprised when different aspects of Sue’s personality came out. The stronger his concept of her was, the more he was unhappy when she didn’t act according to it.

How strange to think we completely understand another person! We don’t even understand ourselves and the changes we go through. We don’t understand everything about a speck of dust, let alone about another person. The false conception that believes someone is who we think he or she is makes our lives complicated. On the other hand if we are aware that our concept is only an opinion, then we’ll be much more flexible.

For example, parents may form a fixed conception of their teenager’s personality and how she should behave. When their child misbehaves, the parents are shocked and a family quarrel ensues. However, if the parents understand that their child is a constantly changing person like themselves, then they won’t have such a strong emotional reaction to her behavior. With a calm mind free of expectations the parents can be more effective in helping their maturing child.

When others act in ways which don’t correspond with our concepts of them we become disappointed or angry. We may try to cajole them into becoming what we expected. We may nag them, boss them around or try to make them feel guilty. When we do this our relationship deteriorates further, and we’re miserable.

The sources of the pain and confusion are our own biased projections and the selfish expectations we’ve placed on others. These are the foundation of attachment. Attachment overestimates our friends and relatives and clings to them. It opens the door for us to be upset and angry later. When we’re separated from our dear ones we’re lonely; when they’re in a bad mood we resent it. If they fail and don’t achieve what we’d counted on we feel betrayed.

To avoid the difficulties caused by attachment we must be aware of how attachment operates. Then we can prevent it by correcting our false preconceptions of others and not projecting new ones. We’ll remember that people are constantly changing and they don’t have fixed personalities. Recalling that it’s impossible for us always to be with our dear ones, we won’t be so upset when we’re separated. Rather than feeling dejected because we aren’t together, we’ll rejoice for the time we had together.

I love you if ...

“Checklist love” isn’t love, for it has strings attached. We think, “I love you if. .. ,” and we fill in our requirements. It’s difficult for us to sincerely care about others when they must fulfill certain requirements which center around the benefit they must give to us. In addition, we’re often fickle in what qualities and behavior we want from others. One day we want our dear one to take the initiative; the next day we want him or her to be dependent.

What we call love is often attachment, a disturbing attitude that overestimates the qualities of the other person. We then cling to him or her thinking our happiness depends on that person. Love, on the other hand, is an open and relaxed attitude. We want someone to be happy simply because he or she exists.

While attachment is uncontrolled and sentimental, love is direct and powerful. Attachment obscures our judgment and we become partial, helping our dear ones and harming those we don’t like. Love clarifies our minds, and we assess a situation by thinking of the greatest good for everyone. Attachment is based on selfishness, while love is founded upon cherishing others.

Attachment values others’ superficial qualities: their looks, intelligence, talents, social status and so on. Love looks beyond these superficial appearances and dwells on the fact that they are just like us: they want happiness and want to avoid suffering. If we see unattractive, dirty, ignorant people, we feel repulsed because our selfish minds want to know attractive, clean and talented people. Love, on the other hand, doesn’t evaluate others by these superficial standards and looks deeper. Love recognizes that regardless of others’ appearances, their experience is similar to ours: they seek to be happy and to avoid problems.

This is a profound point which determines whether we feel alienated or related to those around us. In public places, we look at those around us and often comment on them to ourselves, “He’s too fat, she walks funny, he certainly has a sour expression, she’s arrogant.” Of course we don’t feel close to others when we allow our negative thoughts to pick out their faults.

When we catch ourselves thinking like this, we can pause and then regard the same people through different eyes: “Each one of these people has their own internal experience. Each one only wants to be happy. I know what that’s like, because I’m the same way. They all want encouragement, kindness, or even a smile from others. None of them enjoys criticism or disrespect. They’re exactly like me!” When we think like this, love arises and instead of feeling distant from others, we feel connected to them.

Attachment makes us possessive of the people we’re close to. Someone is MY wife, husband, child, parent. Sometimes we act as if people were our possessions and we were justified in telling them how to live their lives. However, we don’t own our dear ones. We don’t possess people like we do objects.

Recognizing that we never possess others causes attachment to subside. It opens the door for love, which genuinely treasures every living being. We may still advise others and tell them how their actions influence us, but we respect their integrity as individuals.

Fulfilling our needs

When we’re attached we’re not emotionally free. We overly depend on and cling to another person to fulfill our emotional needs. We fear losing him or her, feeling we’d be incomplete without our dear one. Our self-concept is based on having a particular relationship: “I am so-and-so’s husband, wife, parent, child, etc.” Being so dependent, we don’t allow ourselves to develop our own qualities. In addition, by being too dependent we set ourselves up for depression, because no relationship can continue forever. We separate when life ends, if not sooner.

The lack of emotional freedom linked to attachment may also make us feel obliged to care for the other rather than risk rosing him or her. Our affection then lacks sincerity, for it’s based on fear. Or we may be over-eager to help our dear one in order to ensure his or her affection. We may be overprotective, fearful something unexpected will happen to the other person, or we may be jealous when he or she has affection for others.

Love is more selfless. Instead of wondering “How can this relationship fulfill my needs?” we’ll think, “What can I give to the other?” We’ll accept that it’s impossible for others to remove our feelings of emotional poverty and insecurity. The problem isn’t that others don’t satisfy our emotional needs, it’s that we overemphasize our needs and expect too much.

For example, we may feel that we can’t live without someone we’re particularly close to. This is an exaggeration. We have our own dignity as human beings; we needn’t cling to others as if they were the source of all happiness. It’s helpful to remember we’ve lived most of our lives without being with our dear one. Furthermore, other people live very well without him or her.

This doesn’t mean, however, that we should suppress our emotional needs or become aloof and independent, for that doesn’t solve the problem. We must recognize our unrealistic needs and slowly seek to eliminate them. Some emotional needs may be so strong that they can’t be dissolved immediately. If we try to suppress them or pretend they don’t exist, we might become unduly anxious or insecure. In this case, we can try to fulfill these needs while simultaneously working gradually to subdue them.

The core problem is we seek to be loved rather than to love. We yearn to be understood by others rather than to understand them. Our sense of emotional insecurity comes from the ignorance and selfishness obscuring our minds. We can develop self-confidence by recognizing our inner potential to become a complete, satisfied and loving person. When we get in touch with our own potential to become an enlightened being with many magnificent qualities, we’ll develop a true and accurate feeling of self-confidence. We’ll then seek to increase our love, compassion, generosity, patience, concentration and wisdom and to share these qualities with others.

Emotional insecurity makes us continuously seek something from others. Our kindness to them is contaminated by the ulterior motive of wanting to receive something in return. However, when we recognize how much we’ve already received from others, we’ll want to repay their kindness and our hearts will be filled with love. Love emphasizes giving rather than receiving. Not being bound by our cravings and expectations from others, we’ll be open, kind and sharing, yet we’ll maintain our own sense of integrity and autonomy.

Attachment wants others to be happy so much that we pressure their into doing what we think. will make them happy. We give others no choice for we feel we know what’s best for them. We don’t allow them to do what makes them happy, nor do we accept that sometimes they’ll be unhappy. Such difficulties often arise in family relationships.

Love intensely wishes others to be happy. However, it’s tempered with wisdom, recognizing that whether or not others are happy also depends on them. We can guide them, but our egos won’t be involved when we do. Respecting them, we’ll give them the choice of whether or not to accept our advice and our help. Interestingly, when we don’t pressure others to follow our advice they’re more open to listening to it.

Under the influence of attachment we’re bound by our emotional reactions to others. When they’re nice to us we’re happy. When they ignore us or speak sharply to us, we take it personally and are unhappy. But pacifying attachment doesn’t mean we become hard-hearted. Rather, without attachment there will be space in our hearts for genuine affection and impartial love for others. We’ll be actively involved with them.

If we subdue our attachment we can still have friends. These friendships will be richer because of the freedom and respect they’ll be based on. We’ll care about the happiness and misery of all beings equally, simply because everyone is the same in wanting happiness and not wanting suffering. However, our lifestyles and interests may be more compatible with those of some people. Due to close connections we’ve had with some people in previous lives, it will be easy to communicate with them in this lifetime. In any case, our friendships will be based on mutual interests and the wish to help each other become enlightened.

When relationships end

Attachment is accompanied by the preconception that relationships last forever. Although intellectually we may know this isn’t true, deep inside we long to always be with our dear ones. This clinging makes separation even more difficult, for when a dear one dies or moves away we feel as if part of ourselves were lost.

This is not to say that grief is bad. However, it’s helpful to recognize that often attachment is the source of grief and depression. When our own identity is too mixed in with that of another person, we’ll become depressed when we separate. When we refuse to accept deep in our hearts that life is transient, then we set ourselves up to experience pain when our dear ones die.

At the time of the Buddha, a woman was distraught when her infant died. Hysterical, she brought the dead body of her beloved child to the Buddha and asked him to revive it. The Buddha told her fIrst to bring some mustard seeds from a home in which no one had died.

Mustard seeds were found in every home in India; however, she couldn’t find a household in which no one had died. After a while she accepted in her heart that everyone dies, and the grief for her child subsided.

Bringing our understanding of impermanence from our heads to our hearts enables us also to appreciate the time we have with others. Rather than grasping for more, when more isn’t available we’ll rejoice at what we share with others in the present. By thus avoiding attachment, our relationships will be enriched.

TỪ ĐIỂN HỮU ÍCH CHO NGƯỜI HỌC TIẾNG ANH

DO NXB LIÊN PHẬT HỘI PHÁT HÀNH

Mua sách qua Amazon sẽ được gửi đến tận nhà - trên toàn nước Mỹ, Canada, Âu châu và Úc châu.

Quý vị đang truy cập từ IP 216.73.216.23, 147.243.245.176 và chưa ghi danh hoặc đăng nhập trên máy tính này. Nếu là thành viên, quý vị chỉ cần đăng nhập một lần duy nhất trên thiết bị truy cập, bằng email và mật khẩu đã chọn.

Chúng tôi khuyến khích việc ghi danh thành viên ,để thuận tiện trong việc chia sẻ thông tin, chia sẻ kinh nghiệm sống giữa các thành viên, đồng thời quý vị cũng sẽ nhận được sự hỗ trợ kỹ thuật từ Ban Quản Trị trong quá trình sử dụng website này.

Việc ghi danh là hoàn toàn miễn phí và tự nguyện.

Ghi danh hoặc đăng nhập

... ...

Trang chủ

Trang chủ