Điều bất hạnh nhất đối với một con người không phải là khi không có trong tay tiền bạc, của cải, mà chính là khi cảm thấy mình không có ai để yêu thương.Tủ sách Rộng Mở Tâm Hồn

Càng giúp người khác thì mình càng có nhiều hơn; càng cho người khác thì mình càng được nhiều hơn.Lão tử (Đạo đức kinh)

Dầu giữa bãi chiến trường, thắng ngàn ngàn quân địch, không bằng tự thắng mình, thật chiến thắng tối thượng.Kinh Pháp cú (Kệ số 103)

Cho dù người ta có tin vào tôn giáo hay không, có tin vào sự tái sinh hay không, thì ai ai cũng đều phải trân trọng lòng tốt và tâm từ bi. (Whether one believes in a religion or not, and whether one believes in rebirth or not, there isn't anyone who doesn't appreciate kindness and compassion.)Đức Đạt-lai Lạt-ma XIV

Niềm vui cao cả nhất là niềm vui của sự học hỏi. (The noblest pleasure is the joy of understanding.)Leonardo da Vinci

Trời sinh voi sinh cỏ, nhưng cỏ không mọc trước miệng voi. (God gives every bird a worm, but he does not throw it into the nest. )Ngạn ngữ Thụy Điển

Đừng chọn sống an nhàn khi bạn vẫn còn đủ sức vượt qua khó nhọc.Sưu tầm

"Nó mắng tôi, đánh tôi, Nó thắng tôi, cướp tôi." Ai ôm hiềm hận ấy, hận thù không thể nguôi.Kinh Pháp cú (Kệ số 3)

Người trí dù khoảnh khắc kề cận bậc hiền minh, cũng hiểu ngay lý pháp, như lưỡi nếm vị canh.Kinh Pháp Cú - Kệ số 65

Thành công có nghĩa là đóng góp nhiều hơn cho cuộc đời so với những gì cuộc đời mang đến cho bạn. (To do more for the world than the world does for you, that is success. )Henry Ford

Người ngu nghĩ mình ngu, nhờ vậy thành có trí. Người ngu tưởng có trí, thật xứng gọi chí ngu.Kinh Pháp cú (Kệ số 63)

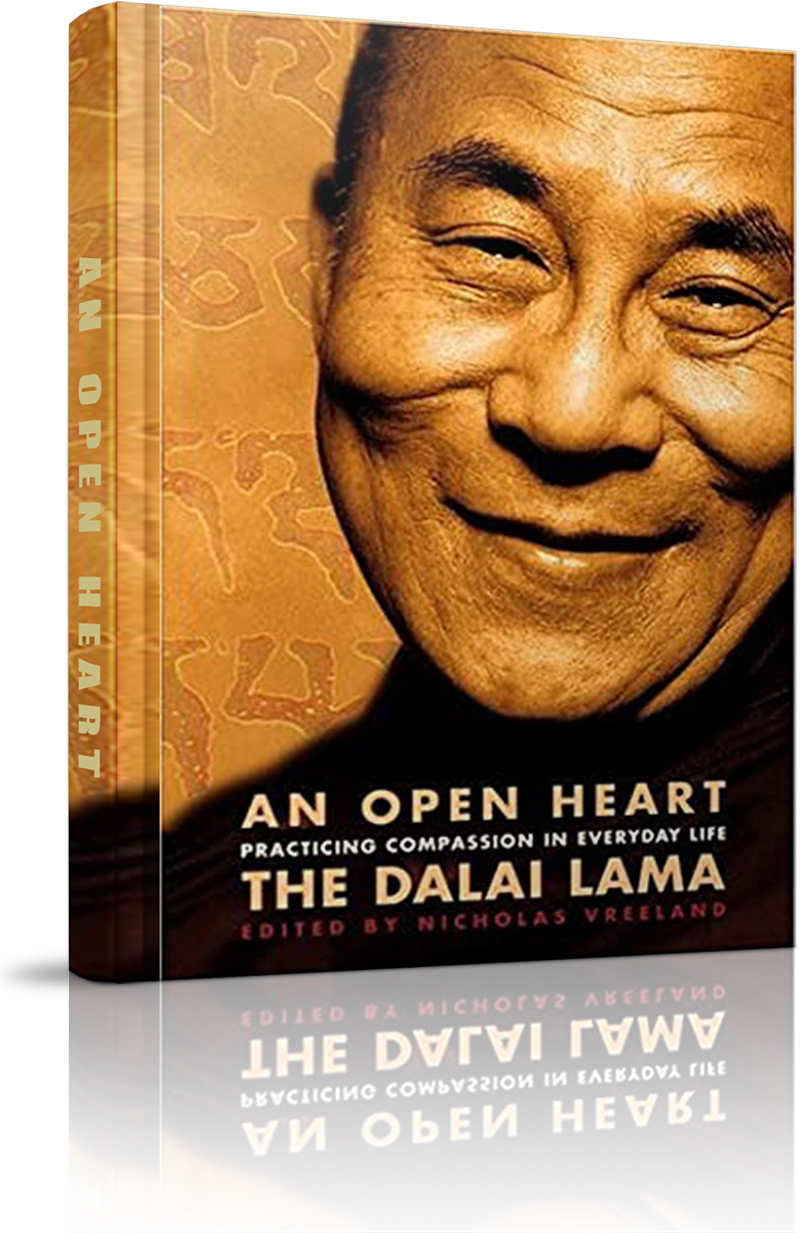

Trang chủ »» Danh mục »» SÁCH ANH NGỮ HOẶC SONG NGỮ ANH-VIỆT »» An Open Heart »» Chapter 11: Calm abiding »»

An Open Heart

»» Chapter 11: Calm abiding

Xem Mục lục

Xem Mục lục  Vietnamese || Đối chiếu song ngữ

Vietnamese || Đối chiếu song ngữ

- none

- Introduction

- Chapter One: The desire for happiness

- Chapter Two: Meditation - A beginning

- Chapter 3: The material and immaterial world

- Chapter 4: Karma

- Chapter 5: The afflictions

- Chapter 6: The vast and the profound: Two aspects of the Path

- Chapter 7: Compassion

- Chapter 8: Meditating on compassion

- Chapter 9: Cultivating equanimity

- Chapter 10: Bodhicitta

- »» Chapter 11: Calm abiding

- Chapter 12: The nine stages of calm abiding meditation

- Chapter 13: Wisdom

- Chapter 14: Buddhahood

- Chapter 15: Generating Bodhicitta

- Afterword (Khyongla Rato and Richard Gere)

- none

In this meditation practice, as with all the others, motivation is once again all-important. The skill involved in concentrating on a single object can be used to various ends. It is a purely technical expertise, and its outcome is determined by your motivation. Naturally, as spiritual practitioners, we are interested in a virtuous motivation and a virtuous end. Let us now analyze the technical aspects of this practice.

Calm abiding is practiced by members of many faiths. A meditator begins the process of training his or her mind by choosing an object of meditation. A Christian practitioner may take the holy cross or the Virgin Mary as the single point of his or her meditation. It might be harder for a Muslim practitioner because of the lack of imagery in Islam, though one could take one’s faith in Allah, for the object of meditation need not be a physical or even a visual object. Therefore, one can maintain one’s focus on a deep faith in God. One might also concentrate on the holy city of Mecca. Buddhist texts often use the image of Shakyamuni Buddha as an example of an object of concentration. One of the benefits of this is that it allows one’s awareness of the great qualities of a Buddha to grow, along with one’s appreciation of his kindness. The result is a greater sense of closeness to the Buddha.

The image of the Buddha that you focus on in this meditation should not be a painting or statue. Though you may use a material image to familiarize yourself with the shape and proportions of the Buddha, it is the mental image of the Buddha that you must concentrate upon. Your visualization of the Buddha should be conjured in your mind. Once it has been, the process of calm abiding can begin.

The Buddha you visualize should be neither too far away from you nor too close. About four feet directly in front of you, at the level of your eyebrows, is correct. The size of the image you visualize should be three or four inches high or smaller. It is helpful to visualize a small image, though quite bright, as if made of light. Visualizing a radiant image helps undermine the natural tendency toward mental torpor or sleepiness. On the other hand, you should also try to imagine this image as being fairly heavy. If the image of the Buddha is perceived to have some kind of weight to it, then the inclination toward mental restlessness can be averted.

Whatever object of meditation you choose, your single-pointed concentration must possess the qualities of stability and clarity. Stability is undermined by excitement, the scattered, distracted quality of mind that is one aspect of attachment. The mind is easily distracted by thoughts of desirable objects. Such thoughts keep us from developing the stable, settled quality necessary for us to abide truly and calmly on the object we have chosen. Clarity, on the other hand, is hindered more by mental laxity, what is sometimes called a sinking quality of mind.

Developing calm abiding demands that you devote yourself to the process utterly until you master it. A calm, quiet environment is said to be essential, as is having supportive friends. You should put aside worldly preoccupations - family, business, or social involvements - and dedicate yourself exclusively to developing concentration. In the beginning, it is best to engage in many short meditation sessions throughout the course of the day. As many as ten to twenty sessions of between fifteen and twenty minutes each might be appropriate. As your concentration develops, you can extend the length of your sessions and diminish their frequency. You should sit in a formal meditative position, with your back straight. If you pursue your practice diligently, it is possible to attain calm abiding in as little as six months.

A meditator must learn to apply antidotes to hindrances as they occur. When the mind seems to be getting excited and begins to drift off toward some pleasant memory or pressing obligation, it must be caught and brought back to focus on its chosen object. Mindfulness, once again, is the tool for doing so. When you first begin to develop calm abiding, it is difficult to keep the mind placed on its object for more than a moment. By means of mindfulness you redirect the mind, returning it again and again to the object. Once the mind is focused on its object, it is with mindfulness that it then remains placed there, without drifting off.

Introspection ensures that our focus remains stable and clear. By means of introspection we are able to catch the mind as it becomes excited or scattered. People who are very energetic and alert are sometimes not able to look you in the eye as they speak to you. They are constantly looking here and there. The scattered mind is a bit like that, unable to remain focused because of its excited condition. Introspection enables us to withdraw the mind a bit by focusing inward, thereby diminishing our mental excitement. This reestablishes the mind’s stability.

Introspection also catches the mind as it becomes lax and lethargic, quickly bringing it back to the object at hand. This is generally a problem for those who are withdrawn by nature. Your meditation becomes too relaxed, lacking in vitality. Vigilant introspection enables you to lift up your mind with thoughts of a joyful nature, thereby increasing your mental clarity and acuity.

As you begin to cultivate calm abiding, it soon becomes apparent that maintaining your focus on the chosen object for even a short period of time is a great challenge. Don’t be discouraged. We see this as a positive sign because you are at last becoming aware of the extreme activity of your mind. By persevering in your practice and skillfully applying mindfulness and introspection, you become able to prolong the duration of your single-pointed concentration, the focus on the chosen object, while also maintaining alertness, the vitality and vibrancy of thought.

There are many sorts of objects, material and notional, that can be used to develop single-pointed concentration. You can cultivate calm abiding by taking consciousness itself as the focus of your meditation. However, it is not easy to have a clear concept of what consciousness is, as this understanding cannot come about from a merely verbal description. A true understanding of the nature of the mind must come from experience.

How should this understanding be cultivated? First, you must look carefully at your experience of thoughts and emotions, the way consciousness arises in you, the way your mind works. Most of the time we experience the mind or consciousness through our interactions with the external world - our memories and our future projections. Are you irritable in the morning? Dazed in the evening? Are you haunted by a failed relationship? Worried about a child’s health? Put all this aside. The true nature of the mind, a clear experience of our knowing, is obscured in our normal experience. When meditating on the mind, you must try to remain focused on the present moment. You must prevent recollections of past experiences from interfering with your reflections. The mind should not be directed back into the past, nor influenced by hopes or fears about the future.

Once you prevent such thoughts from interfering with your focus, what is left is the interval between the recollections of past experiences and your anticipations and projections of the future. This interval is a vacuum. You must work at maintaining your focus on just this vacuum.

Initially, your experience of this interval space is only fleeting. However, as you continue to practice, you become able to prolong it. In doing so, you clear away the thoughts that obstruct the expression of the real nature of the mind. Gradually, pure knowing can shine through. With practice, that interval can get larger and larger, until it becomes possible for you to know what consciousness is. It is important to understand that the experience of this mental interval - consciousness emptied of all thought processes - is not some kind of blank mind. It is not what one experiences when in deep, dreamless sleep or when one has fainted.

At the beginning of your meditation you should say to yourself, “I will not allow my mind to be distracted by thoughts of the future, anticipations, hopes, or fears, nor will I let my mind stray toward memories of the past. I will remain focused on this present moment.” Once you have cultivated such a will, you take that space between past and future as the object of meditation and simply maintain your awareness of it, free of any conceptual thought processes.

THE TWO LEVELS OF MIND

Mind has two levels by nature. The first level is the clear experience of knowing just described. The second and ultimate nature of the mind is experienced with the realization of the absence of this mind’s inherent existence. In order to develop single-pointed concentration on the ultimate nature of the mind, you initially take the first level of the mind - the clear experience of knowing - as the focus of meditation. Once that focus is achieved, you then contemplate the mind’s lack of inherent existence. What then appears to the mind is actually the emptiness or lack of any intrinsic existence of the mind.

That is the first step. Then you take this emptiness as your object of concentration. This is a very difficult and challenging form of meditation. It is said that a practitioner of the highest caliber must first cultivate an understanding of emptiness and then, on the basis of this understanding, use emptiness itself as the object of meditation. However, it is helpful to have some quality of calm abiding to use as a tool in coming to understand emptiness on a deeper level.

MUA THỈNH KINH SÁCH PHẬT HỌC

DO NXB LIÊN PHẬT HỘI PHÁT HÀNH

Mua sách qua Amazon sẽ được gửi đến tận nhà - trên toàn nước Mỹ, Canada, Âu châu và Úc châu.

Quý vị đang truy cập từ IP 216.73.216.157 và chưa ghi danh hoặc đăng nhập trên máy tính này. Nếu là thành viên, quý vị chỉ cần đăng nhập một lần duy nhất trên thiết bị truy cập, bằng email và mật khẩu đã chọn.

Chúng tôi khuyến khích việc ghi danh thành viên ,để thuận tiện trong việc chia sẻ thông tin, chia sẻ kinh nghiệm sống giữa các thành viên, đồng thời quý vị cũng sẽ nhận được sự hỗ trợ kỹ thuật từ Ban Quản Trị trong quá trình sử dụng website này.

Việc ghi danh là hoàn toàn miễn phí và tự nguyện.

Ghi danh hoặc đăng nhập

... ...

Trang chủ

Trang chủ