Người cầu đạo ví như kẻ mặc áo bằng cỏ khô, khi lửa đến gần phải lo tránh. Người học đạo thấy sự tham dục phải lo tránh xa.Kinh Bốn mươi hai chương

Tôn giáo không có nghĩa là giới điều, đền miếu, tu viện hay các dấu hiệu bên ngoài, vì đó chỉ là các yếu tố hỗ trợ trong việc điều phục tâm. Khi tâm được điều phục, mỗi người mới thực sự là một hành giả tôn giáo.Đức Đạt-lai Lạt-ma XIV

Sự ngu ngốc có nghĩa là luôn lặp lại những việc làm như cũ nhưng lại chờ đợi những kết quả khác hơn. (Insanity: doing the same thing over and over again and expecting different results.)Albert Einstein

Nếu chúng ta luôn giúp đỡ lẫn nhau, sẽ không ai còn cần đến vận may. (If we always helped one another, no one would need luck.)Sophocles

Tôi không hóa giải các bất ổn mà hóa giải cách suy nghĩ của mình. Sau đó, các bất ổn sẽ tự chúng được hóa giải. (I do not fix problems. I fix my thinking. Then problems fix themselves.)Louise Hay

Khi bạn dấn thân hoàn thiện các nhu cầu của tha nhân, các nhu cầu của bạn cũng được hoàn thiện như một hệ quả.Đức Đạt-lai Lạt-ma XIV

Điều quan trọng nhất bạn cần biết trong cuộc đời này là bất cứ điều gì cũng có thể học hỏi được.Rộng Mở Tâm Hồn

Bạn nhận biết được tình yêu khi tất cả những gì bạn muốn là mang đến niềm vui cho người mình yêu, ngay cả khi bạn không hiện diện trong niềm vui ấy. (You know it's love when all you want is that person to be happy, even if you're not part of their happiness.)Julia Roberts

Chúng ta không có khả năng giúp đỡ tất cả mọi người, nhưng mỗi người trong chúng ta đều có thể giúp đỡ một ai đó. (We can't help everyone, but everyone can help someone.)Ronald Reagan

Mỗi cơn giận luôn có một nguyên nhân, nhưng rất hiếm khi đó là nguyên nhân chính đáng. (Anger is never without a reason, but seldom with a good one.)Benjamin Franklin

Cơ hội thành công thực sự nằm ở con người chứ không ở công việc. (The real opportunity for success lies within the person and not in the job. )Zig Ziglar

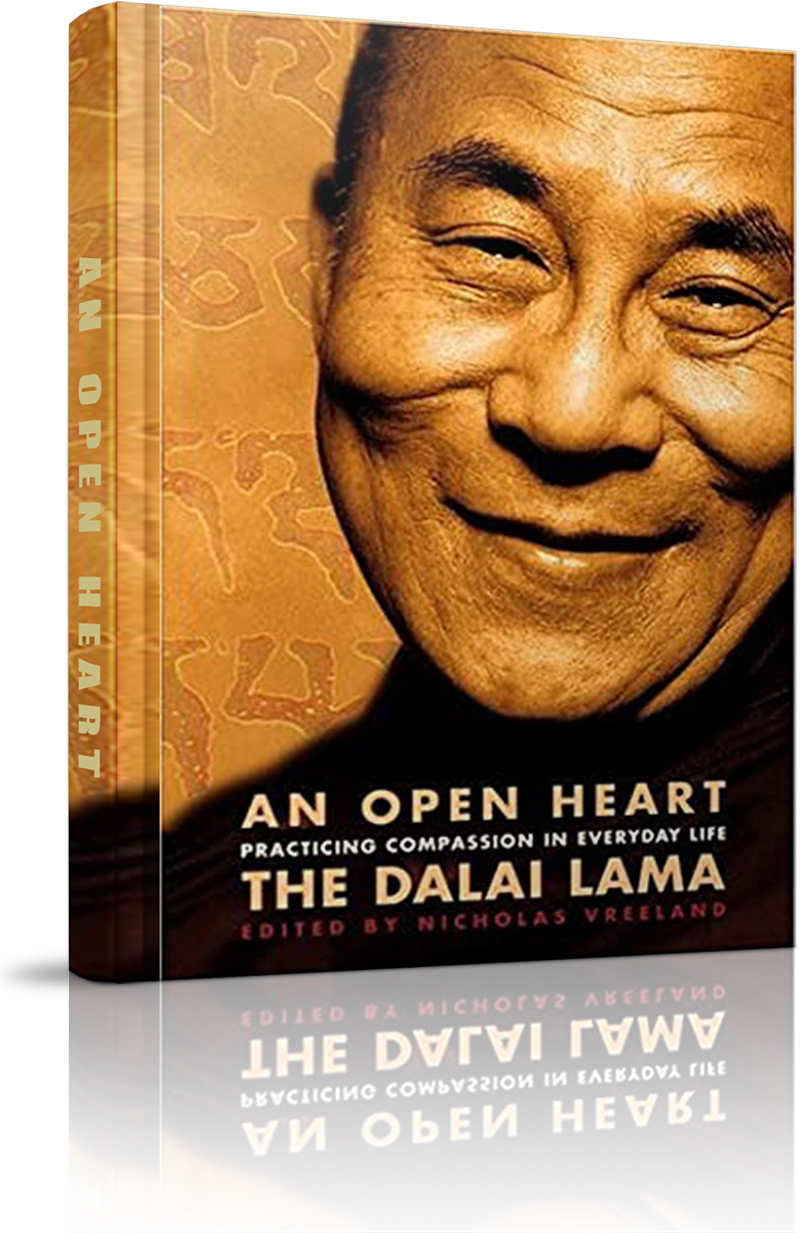

Trang chủ »» Danh mục »» SÁCH ANH NGỮ HOẶC SONG NGỮ ANH-VIỆT »» An Open Heart »» Chapter 6: The vast and the profound: Two aspects of the Path »»

Xem Mục lục

Xem Mục lục  Vietnamese || Đối chiếu song ngữ

Vietnamese || Đối chiếu song ngữ

DO NXB LIÊN PHẬT HỘI PHÁT HÀNH

Mua sách qua Amazon sẽ được gửi đến tận nhà - trên toàn nước Mỹ, Canada, Âu châu và Úc châu.

Quý vị đang truy cập từ IP 216.73.216.61 và chưa ghi danh hoặc đăng nhập trên máy tính này. Nếu là thành viên, quý vị chỉ cần đăng nhập một lần duy nhất trên thiết bị truy cập, bằng email và mật khẩu đã chọn.

Chúng tôi khuyến khích việc ghi danh thành viên ,để thuận tiện trong việc chia sẻ thông tin, chia sẻ kinh nghiệm sống giữa các thành viên, đồng thời quý vị cũng sẽ nhận được sự hỗ trợ kỹ thuật từ Ban Quản Trị trong quá trình sử dụng website này.

Việc ghi danh là hoàn toàn miễn phí và tự nguyện.

Ghi danh hoặc đăng nhập