Sự toàn thiện không thể đạt đến, nhưng nếu hướng theo sự toàn thiện, ta sẽ có được sự tuyệt vời. (Perfection is not attainable, but if we chase perfection we can catch excellence.)Vince Lombardi

Hãy cống hiến cho cuộc đời những gì tốt nhất bạn có và điều tốt nhất sẽ đến với bạn. (Give the world the best you have, and the best will come to you. )Madeline Bridge

Trong sự tu tập nhẫn nhục, kẻ oán thù là người thầy tốt nhất của ta. (In the practice of tolerance, one's enemy is the best teacher.)Đức Đạt-lai Lạt-ma XIV

Ý dẫn đầu các pháp, ý làm chủ, ý tạo; nếu với ý ô nhiễm, nói lên hay hành động, khổ não bước theo sau, như xe, chân vật kéo.Kinh Pháp Cú (Kệ số 1)

Đừng làm một tù nhân của quá khứ, hãy trở thành người kiến tạo tương lai. (Stop being a prisoner of your past. Become the architect of your future. )Robin Sharma

Bạn nhận biết được tình yêu khi tất cả những gì bạn muốn là mang đến niềm vui cho người mình yêu, ngay cả khi bạn không hiện diện trong niềm vui ấy. (You know it's love when all you want is that person to be happy, even if you're not part of their happiness.)Julia Roberts

Đừng cố trở nên một người thành đạt, tốt hơn nên cố gắng trở thành một người có phẩm giá. (Try not to become a man of success, but rather try to become a man of value.)Albert Einstein

Dầu giữa bãi chiến trường, thắng ngàn ngàn quân địch, không bằng tự thắng mình, thật chiến thắng tối thượng.Kinh Pháp cú (Kệ số 103)

Khó khăn thách thức làm cho cuộc sống trở nên thú vị và chính sự vượt qua thách thức mới làm cho cuộc sống có ý nghĩa. (Challenges are what make life interesting and overcoming them is what makes life meaningful. )Joshua J. Marine

Người thành công là người có thể xây dựng một nền tảng vững chắc bằng chính những viên gạch người khác đã ném vào anh ta. (A successful man is one who can lay a firm foundation with the bricks others have thrown at him.)David Brinkley

Điều quan trọng nhất bạn cần biết trong cuộc đời này là bất cứ điều gì cũng có thể học hỏi được.Rộng Mở Tâm Hồn

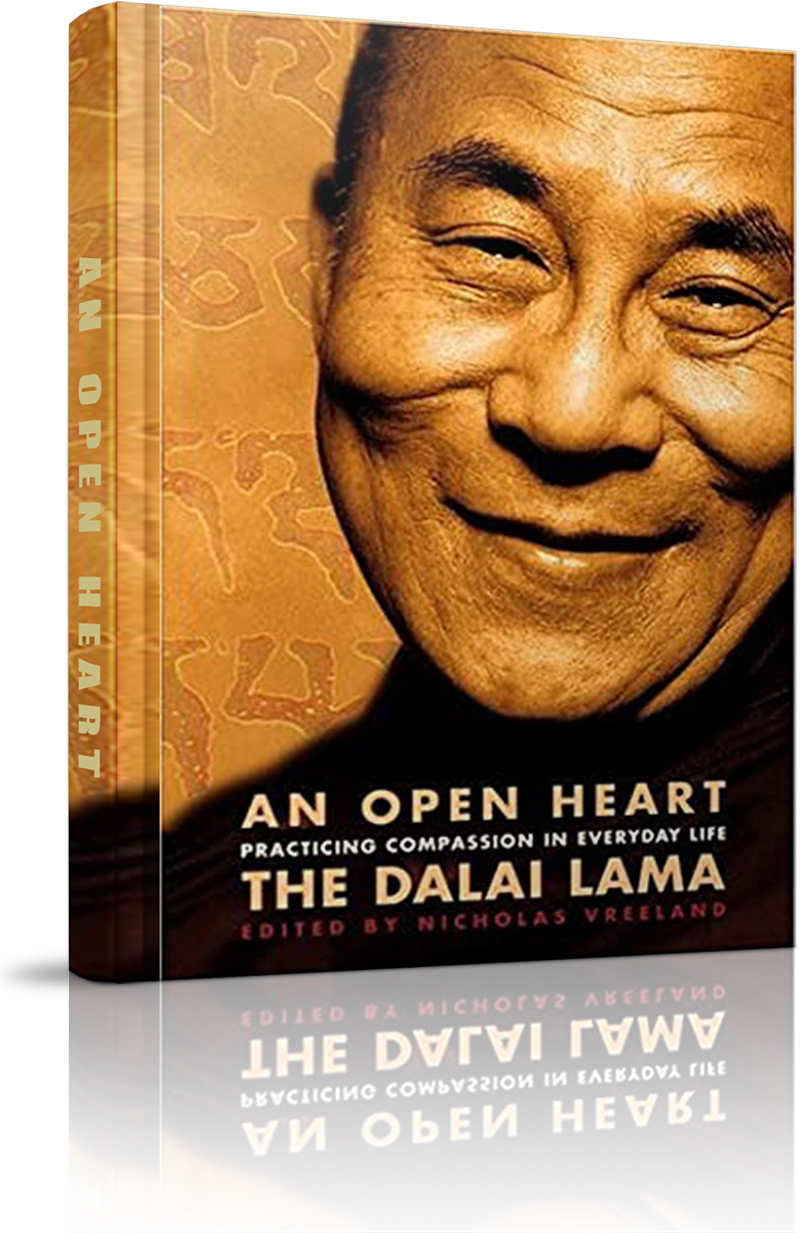

Trang chủ »» Danh mục »» SÁCH ANH NGỮ HOẶC SONG NGỮ ANH-VIỆT »» An Open Heart »» Chapter 8: Meditating on compassion »»

An Open Heart

»» Chapter 8: Meditating on compassion

Xem Mục lục

Xem Mục lục  Vietnamese || Đối chiếu song ngữ

Vietnamese || Đối chiếu song ngữ

- none

- Introduction

- Chapter One: The desire for happiness

- Chapter Two: Meditation - A beginning

- Chapter 3: The material and immaterial world

- Chapter 4: Karma

- Chapter 5: The afflictions

- Chapter 6: The vast and the profound: Two aspects of the Path

- Chapter 7: Compassion

- »» Chapter 8: Meditating on compassion

- Chapter 9: Cultivating equanimity

- Chapter 10: Bodhicitta

- Chapter 11: Calm abiding

- Chapter 12: The nine stages of calm abiding meditation

- Chapter 13: Wisdom

- Chapter 14: Buddhahood

- Chapter 15: Generating Bodhicitta

- Afterword (Khyongla Rato and Richard Gere)

- none

The compassion that we must ultimately possess is derived from our insight into emptiness, the ultimate nature of reality. It is at this point that the vast meets the profound. This ultimate nature, as explained in Chapter 6, “The Vast and the Profound,” is the absence of inherent existence in all aspects of reality, the absence of intrinsic identity in all phenomena. We attribute this quality of inherent existence to our mind and body, and then perceive this objective status - the self, or “me.” This strong sense of self then grasps at some kind of inherent nature of phenomena, such as a quality of carness in a new car we fancy.

And as a result of such reification and our ensuing grasping, we may also experience emotions such as anger or unhappiness in the event that we are denied the object of our desire: the car, the new computer, or whatever it may be. Reification simply means that we give such objects a reality they don’t have.

When compassion is joined with this understanding of how all our suffering derives from our misconception about the nature of reality, we have reached the next step on our spiritual journey. As we recognize that the basis of misery is this mistaken perception, this mistaken grasping at a nonexistent self, we see that suffering can be eliminated. Once we remove the mistaken perception, we shall no longer be troubled by suffering.

Knowing that people’s suffering is avoidable, that it is surmountable, our sympathy for their inability to extricate themselves leads to a more powerful compassion. Otherwise, though our compassion may be strong, it is likely to have a quality of hopelessness, even despair.

HOW TO MEDITATE ON COMPASSION AND LOVING-KINDNESS?

If we truly intend to develop compassion, we have to devote more time to it than our formal meditation sessions grant us. It is a goal we must commit ourselves to with all our heart. If we do have a time each day when we like to sit and contemplate, that is very good. As I have suggested, early mornings are a good time for such contemplation, since our minds are particularly clear then. We must, however, devote more than just this period to cultivating compassion. During our more formal sessions, for example, we work at developing empathy and closeness to others. We reflect upon their miserable predicament.

And once we have generated a true feeling of compassion within ourselves, we should hold on to it, simply experience it, using the settled meditation I have described to remain focused, without applying thought or reason. This enables it to sink in. And when the feeling begins to weaken, we again apply reasons to restimulate our compassion. We go between these two methods of meditation, much as potters work their clay, moistening it and then forming it as they see the need.

It is generally best that we initially not spend too much time in formal meditation. We shall not generate compassion for all beings overnight. We won’t succeed in a month or a year. If we are able to diminish our selfish instincts and develop a little more concern for others before our death, we have made good use of this life. If, instead, we push ourselves to attain Buddhahood in a short time, we’ll soon grow tired of our practice. The mere sight of the seat where we engage in our formal morning meditation will stimulate resistance.

GREAT COMPASSION

It is said that the ultimate state of Buddhahood is attainable within a human lifetime. This is for extraordinary practitioners who have devoted many previous lives to preparing themselves for this opportunity. We can feel only admiration for such beings and use their example to develop perseverance instead of pushing ourselves to any extreme. It is best to pursue a middle path between lethargy and fanaticism.

We should ensure that whatever we do, we maintain some effect or influence from our meditation so that it directs our actions as we live our everyday lives. By our doing so, everything we do outside our formal sessions becomes part of our training in compassion. It is not difficult for us to develop sympathy for a child in the hospital or an acquaintance mourning the death of a spouse. We must start to consider how to keep our hearts open toward those we would normally envy, those who enjoy fine lifestyles and wealth. With an ever deeper recognition of what suffering is, gained from our meditation sessions, we become able to relate to such people with compassion.

Eventually we should be able to relate to all beings this way, seeing that their situation is always dependent upon the conditions of the vicious cycle of life. In this way all interactions with others become catalysts for deepening our compassion. This is how we keep our hearts open in our daily lives, outside of our formal meditation periods.

True compassion has the intensity and spontaneity of a loving mother caring for her suffering baby. Throughout the day, such a mother’s concern for her child affects all her thoughts and actions. This is the attitude we are working to cultivate toward each and every being. When we experience this, we have generated “great compassion.”

Once one has become profoundly moved by great compassion and loving-kindness, and had one’s heart stirred by altruistic thoughts, one must pledge to devote oneself to freeing all beings from the suffering they endure within cyclic existence, the vicious circle of birth, death, and rebirth we are all prisoners of. Our suffering is not limited to our present situation. According to the Buddhist view, our present situation as humans is relatively comfortable. However, we stand to experience much difficulty in the future if we misuse this present opportunity. Compassion enables us to refrain from thinking in a self-centered way. We experience great joy and never fall to the extreme of simply seeking our own personal happiness and salvation. We continually strive to develop and perfect our virtue and wisdom. With such compassion, we shall eventually possess all the necessary conditions for attaining enlightenment. We must therefore cultivate compassion from the very start of our spiritual practice.

So far, we have dealt with those practices that enable us to refrain from unwholesome behavior. We have discussed how the mind works and how we must work on it much as we would work on a physical object, by applying certain actions in order to bring about desired results. We recognize the process of opening our hearts to be no different. There is no secret method by which compassion and loving-kindness can come about. We must knead our minds skillfully, and with patience and perseverance we shall find that our concern for the well-being of others will grow.

TỪ ĐIỂN HỮU ÍCH CHO NGƯỜI HỌC TIẾNG ANH

DO NXB LIÊN PHẬT HỘI PHÁT HÀNH

Mua sách qua Amazon sẽ được gửi đến tận nhà - trên toàn nước Mỹ, Canada, Âu châu và Úc châu.

Quý vị đang truy cập từ IP 216.73.216.157 và chưa ghi danh hoặc đăng nhập trên máy tính này. Nếu là thành viên, quý vị chỉ cần đăng nhập một lần duy nhất trên thiết bị truy cập, bằng email và mật khẩu đã chọn.

Chúng tôi khuyến khích việc ghi danh thành viên ,để thuận tiện trong việc chia sẻ thông tin, chia sẻ kinh nghiệm sống giữa các thành viên, đồng thời quý vị cũng sẽ nhận được sự hỗ trợ kỹ thuật từ Ban Quản Trị trong quá trình sử dụng website này.

Việc ghi danh là hoàn toàn miễn phí và tự nguyện.

Ghi danh hoặc đăng nhập

... ...

Trang chủ

Trang chủ