This book began life as a relatively simple assignment of splicing together transcripts of Yongey Mingyur Rinpoche’s early public lectures at Buddhist centers around the world and editing the whole into a somewhat logically structured manuscript. (It should be noted that “Rinpoche” - which may be roughly translated from the Tibetan as “precious one” - is a title appended to the name of a great master, similar to the way the title “Ph.D.” is appended to the name of a person deemed expert in various branches of Western study. According to Tibetan tradition, a master granted the title of Rinpoche is often addressed or referred to by the title alone.)

As is often the case, however, simple tasks tend to assume lives of their own, growing beyond their initial scope into much larger projects. Since most of the transcripts I’d received had been drawn from Yongey Mingyur’s early years of teaching, they didn’t reflect the detailed understanding of modern science he had acquired through his later discussions with European and North American scientists, his participation in the Mind and Life Institute conferences, and his personal experience as a research subject at the Waisman Laboratory for Brain Imaging and Behavior at the University of Wisconsin, Madison.

Fortunately, an opportunity to work directly with Yongey Mingyur on the manuscript opened up when he took a break from his worldwide teaching schedule for an extended stay in Nepal during the closing months of 2004. I must admit that I was inspired more by dread than by excitement over the prospect of spending several months in a country beset by conflict between government and insurgent factions. But whatever inconveniences I experienced during my stay there were more than offset by the extraordinary chance to spend an hour or two every day in the company of one of the most charismatic, intelligent, and knowledgeable teachers I have ever had the privilege of knowing.

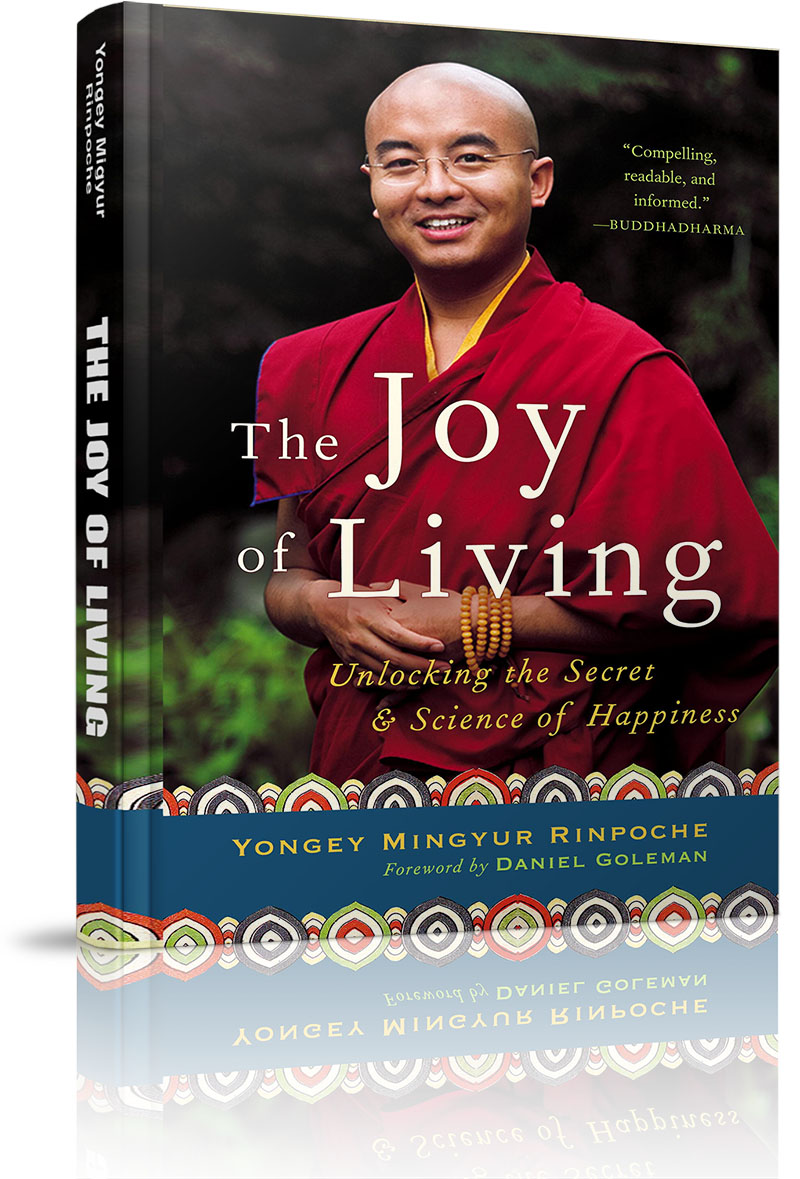

Born in 1975 in Nubri, Nepal, Yongey Mingyur Rinpoche is a rising star among the new generation of Tibetan Buddhist masters trained outside of Tibet. Deeply versed in the practical and philosophical disciplines of an ancient tradition, he is also amazingly conversant in the issues and details of modern culture, having taught for nearly a decade around the world, meeting and speaking with a diverse array of individuals ranging from internationally renowned scientists to suburbanites trying to resolve petty feuds with angry neighbors.

I suspect that the ease with which Rinpoche is able to navigate the complex and sometimes emotionally charged situations he encounters during his worldwide teaching tours stems in part from having been groomed from an early age for the rigors of public life. At the age of three, he was formally recognized by the Sixteenth Karmapa (one of the most highly esteemed Tibetan Buddhist masters of the twentieth century) as the seventh incarnation of Yongey Mingyur Rinpoche, a meditation adept and scholar of the seventeenth century who was noted in particular as a master of advanced methods of Buddhist practice.

At about the same time, Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche informed Rinpoche’s parents that their son was also the incarnation of Kyabje Kangyur Rinpoche, a meditation master of immense practical genius - who, as one of the first of the great Tibetan masters to voluntarily accept exile from his homeland in the wake of the political changes that began to shake Tibet in the 1950s, commanded until his death an enormous audience of both Eastern and Western students.

For those unfamiliar with the particulars of the Tibetan system of reincarnation, a note of explanation may be necessary here.

According to the Tibetan Buddhist tradition, great teachers who have achieved the highest states of enlightenment are said to be moved by enormous compassion to be reborn again and again in order to help all living creatures discover in themselves complete freedom from pain and suffering. The Tibetan term for these passionately committed men and women is tulku, a word that may be roughly translated into English as “physical emanation.” Undoubtedly the best-known tulku of the modern age is the Dalai Lama, whose current incarnation epitomizes the compassionate commitment to the welfare of others ascribed to a reincarnate master.

Whether you choose to believe that the present Yongey Mingyur Rinpoche has carried the same broad range of practical and intellectual skills through successive incarnations or has mastered them through a truly exceptional degree of personal diligence is up to you. What distinguishes the current Yongey Mingyur Rinpoche from previous holders of the title is the worldwide scale of his influence and renown. While previous incarnations of the Yongey Mingyur Rinpoche line of tulkus has been somewhat limited by the geographical and cultural isolation of Tibet, circumstances have conspired to allow the current holder of the title to communicate the depth and breadth of his mastery to an audience of thousands extending from Malaysia to Manhattan to Monterey.

Titles and pedigrees, however, offer little in the way of protection against personal difficulties, of which Yongey Mingyur Rinpoche certainly has had his share. As he relates with great candor, though raised by a loving family in an area of Nepal noted for its pristine beauty, he spent his early years plagued by what would probably be diagnosed by Western specialists as panic disorder. When he first told me about the depth of anxiety that characterized his childhood, I found it hard to believe that this warm, charming, and charismatic young man had spent much of his childhood in a persistent state of fear. It’s a testament not only to his extraordinary strength of character but also to the efficacy of the Tibetan Buddhist practices he presents in this, his first book, that he was able, without recourse to conventional pharmaceutical and therapeutic aid, to master and overcome this affliction.

Rinpoche’s personal testimony is not the only evidence of his triumph over devastating emotional pain. In 2002, as one of eight long-term Buddhist meditation practitioners participating in a study conducted by Antoine Lutz, Ph.D., a neuroscientist trained by Francisco Varela, and Richard Davidson, Ph.D., a world-renowned neuroscientist and a member of the Board of Scientific Counselors of the National Institute of Mental Health, Yongey Mingyur underwent a battery of neurological tests at the Waisman Laboratory in Madison, Wisconsin.

The tests employed state-of-the-art fMRI technology that - unlike standard MRI technology, which provides only a kind of still photograph of brainbody activity - captures a moment-by-moment pictorial record of changing levels of activity in different areas of the brain.

The EEG equipment used to measure the tiny electrical impulses that occur when brain cells communicate was also quite sophisticated. Whereas a typical EEG procedure involves attaching only sixteen electrodes to the scalp in order to measure electrical activity at the surface of the skull, the equipment used in the Waisman lab employed 128 electrodes in order to measure tiny changes in electrical activity deep within the subjects’ brains.

The results of both the fMRI and EEG studies of these eight trained meditators were impressive on two levels. While practicing compassion and loving-kindness meditation, the brain area known to be activated in maternal love and empathy was more prominently activated among long-term Buddhist practitioners than among a group of control subjects who had been given meditation instructions one week prior to the scans and asked to practice daily.

Yongey Mingyur’s capacity to generate such an altruistic and positive state was truly amazing, since even people who don’t suffer panic attacks frequently experience feelings of claustrophobia when lying in the narrow space of an fMRI scanner. The fact that he could focus his mind so capably even in a claustrophobic environment suggests that his meditation training overrode his propensity for panic attacks.

More remarkably, the measurements of the long-term practitioners’ EEG activity during meditation were apparently so far off the scale of normal EEG readings that - as I understand it - the lab technicians thought at first that the machinery might have been malfunctioning. After hastily double-checking their equipment, though, the technicians were forced to eliminate the possibility of mechanical malfunction and confront the reality that the electrical activity associated with attention and phenomenal awareness transcended anything they’d ever witnessed.

In a departure from the typically cautious language of modern scientists, Richard Davidson recalled in a 2005 Time magazine interview, “It was exciting. . . . We didn’t expect to see anything quite that dramatic.”

In the following pages, Yongey Mingyur quite frankly discusses his personal troubles and his struggle to overcome them. He also describes his first childhood meeting with a young Chilean scientist named Francisco Varela, who would eventually become one of the foremost neuroscientists of the twentieth century.

Varela was a student of Yongey Mingyur’s father, Tulku Urgyen Rinpoche, whose teaching engagements in Europe, North America, and Asia attracted thousands of students. Varela developed a close friendship with Yongey Mingyur, introducing him to Western ideas about the nature and function of the human brain.

Seeing his interest in science, others among Tulku Urgyen’s Western students began teaching Yongey Mingyur about physics, biology, and cosmology. These early “science lessons,” offered to him at the age of nine, had a profound effect on him, eventually inspiring him to find a way to bring together the principles of Tibetan Buddhism and modern science in a manner accessible to those who, unable to wade through scientific publications and either skeptical or overwhelmed by the sheer volume of Buddhist books, nevertheless yearned for a practical means of achieving a lasting sense of personal well-being.

Before Yongey Mingyur could begin such a project, however, he had to complete his formal Buddhist education. Between the ages of eleven and thirteen, he traveled back and forth between his father’s hermitage in Nepal and Sherab Ling monastery in India, the primary residence of the Twelfth Tai Situ Rinpoche, one of the most important Tibetan Buddhist teachers alive today.

Under the guidance of the Buddhist masters in Nepal and Sherab Ling, he engaged in an intense study of the sutras, which represent the actual words of the Buddha, and the shastras, a collection of texts that represent Indian Buddhist commentaries on the sutras, as well as seminal texts and commentaries by Tibetan masters. In 1988, at the end of this period, Tai Situ Rinpoche granted him permission to enter the very first three-year retreat program at Sherab Ling.

Created centuries ago in Tibet as the basis of advanced meditation training, the three-year retreat is a highly selective program that involves intensive study of the core techniques of Tibetan Buddhist meditation practice. Yongey Mingyur Rinpoche was one of the youngest students in the known history of Tibetan Buddhism to be allowed to enter this program. His progress during those years was so impressive that after he completed the program, Tai Situ Rinpoche appointed him master of the next retreat at Sherab Ling - making him, at the age of seventeen, the youngest known retreat master in the history of Tibetan Buddhism. In his role as retreat master, Yongey Mingyur completed what amounted to nearly seven years of formal retreat.

In 1994, at the end of the second retreat, he enrolled at a monastic college, known in Tibetan as a shedra, to continue his formal education through intensive study of essential Buddhist texts. The following year, Tai Situ Rinpoche appointed him principal representative of Sherab Ling, overseeing the entire range of the monastery’s activities and reopening the shedra there, where he continued his own studies while also serving as a teacher. For the next several years, Yongey Mingyur Rinpoche divided his time between overseeing the monastery’s activities, teaching and studying at the shedra, and serving as master for yet another three-year retreat. In 1998, at the age of twenty-three, he took full monastic ordination.

Since the age of nineteen - an age when most of us are preoccupied by more worldly interests - Yongey Mingyur has maintained a grueling schedule that includes supervising the activities of monasteries in Nepal and India, worldwide teaching tours, private counseling, committing to memory hundreds of pages of Buddhist texts, and absorbing as much as he can from the last living members of the generation of meditation teachers trained in Tibet.

What has impressed me most during the time I’ve known him, though, is his capacity to meet every challenge with not only an enviable degree of composure, but also with a sharp, ingeniously timed sense of humor. On more than one occasion during my stay in Nepal, while I was droning on over the transcript of our previous day’s conversation, he would sometimes pretend to fall asleep or make as if to bolt out the window. In time I realized he was simply “busting” me for taking the work too seriously, demonstrating in an especially direct manner that a certain amount of levity is essential to Buddhist practice. For if, as the Buddha proposed in the first teachings he gave upon attaining enlightenment, the essence of ordinary life is suffering, then one of the most effective antidotes is laughter - particularly laughter at oneself. Every aspect of experience assumes a certain kind of brightness once you learn to laugh at yourself.

This is perhaps the most important lesson Yongey Mingyur offered me during the time I spent with him in Nepal, and I’m as grateful for it as for the profound insights into the nature of the human mind he has been able to offer through his unique ability to synthesize the subtleties of Tibetan Buddhism and the marvelous revelations of modern science. It is my sincerest hope that everyone who reads this book will find his or her own path through the maze of personal pain, discomfort, and despair that characterizes everyday life, and learn, as I did, how to laugh.

As a final note, most of the citations from Tibetan and Sanskrit texts are the work of other translators, true giants in their fields, to whom I owe a large debt of gratitude for their clarity, scholarship, and insight. Those few citations that are not directly attributed to others represent my own translations, carefully worked out with Yongey Mingyur Rinpoche, whose profound understanding of ancient prayers and classic texts offered me a further glimpse into the character of a true Buddhist master.

ERIC SWANSON

Sự hiểu biết là chưa đủ, chúng ta cần phải biết ứng dụng. Sự nhiệt tình là chưa đủ, chúng ta cần phải bắt tay vào việc. (Knowing is not enough; we must apply. Willing is not enough; we must do.)Johann Wolfgang von Goethe

Xem Mục lục

Xem Mục lục  Vietnamese || Đối chiếu song ngữ

Vietnamese || Đối chiếu song ngữ