Điều kiện duy nhất để cái ác ngự trị chính là khi những người tốt không làm gì cả. (The only thing necessary for the triumph of evil is for good men to do nothing.)Edmund Burke

Các sinh vật đang sống trên địa cầu này, dù là người hay vật, là để cống hiến theo cách riêng của mình, cho cái đẹp và sự thịnh vượng của thế giới.Đức Đạt-lai Lạt-ma XIV

Như ngôi nhà khéo lợp, mưa không xâm nhập vào. Cũng vậy tâm khéo tu, tham dục không xâm nhập.Kinh Pháp cú (Kệ số 14)

Ai sống quán bất tịnh, khéo hộ trì các căn, ăn uống có tiết độ, có lòng tin, tinh cần, ma không uy hiếp được, như núi đá, trước gió.Kinh Pháp Cú (Kệ số 8)

Kỳ tích sẽ xuất hiện khi chúng ta cố gắng trong mọi hoàn cảnh.Sưu tầm

Đừng làm cho người khác những gì mà bạn sẽ tức giận nếu họ làm với bạn. (Do not do to others what angers you if done to you by others. )Socrates

Để sống hạnh phúc bạn cần rất ít, và tất cả đều sẵn có trong chính bạn, trong phương cách suy nghĩ của bạn. (Very little is needed to make a happy life; it is all within yourself, in your way of thinking.)Marcus Aurelius

Thành công là khi bạn đứng dậy nhiều hơn số lần vấp ngã. (Success is falling nine times and getting up ten.)Jon Bon Jovi

Mục đích cuộc đời ta là sống hạnh phúc. (The purpose of our lives is to be happy.)Đức Đạt-lai Lạt-ma XIV

Mặc áo cà sa mà không rời bỏ cấu uế, không thành thật khắc kỷ, thà chẳng mặc còn hơn.Kinh Pháp cú (Kệ số 9)

Chúng ta phải thừa nhận rằng khổ đau của một người hoặc một quốc gia cũng là khổ đau chung của nhân loại; hạnh phúc của một người hay một quốc gia cũng là hạnh phúc của nhân loại.Đức Đạt-lai Lạt-ma XIV

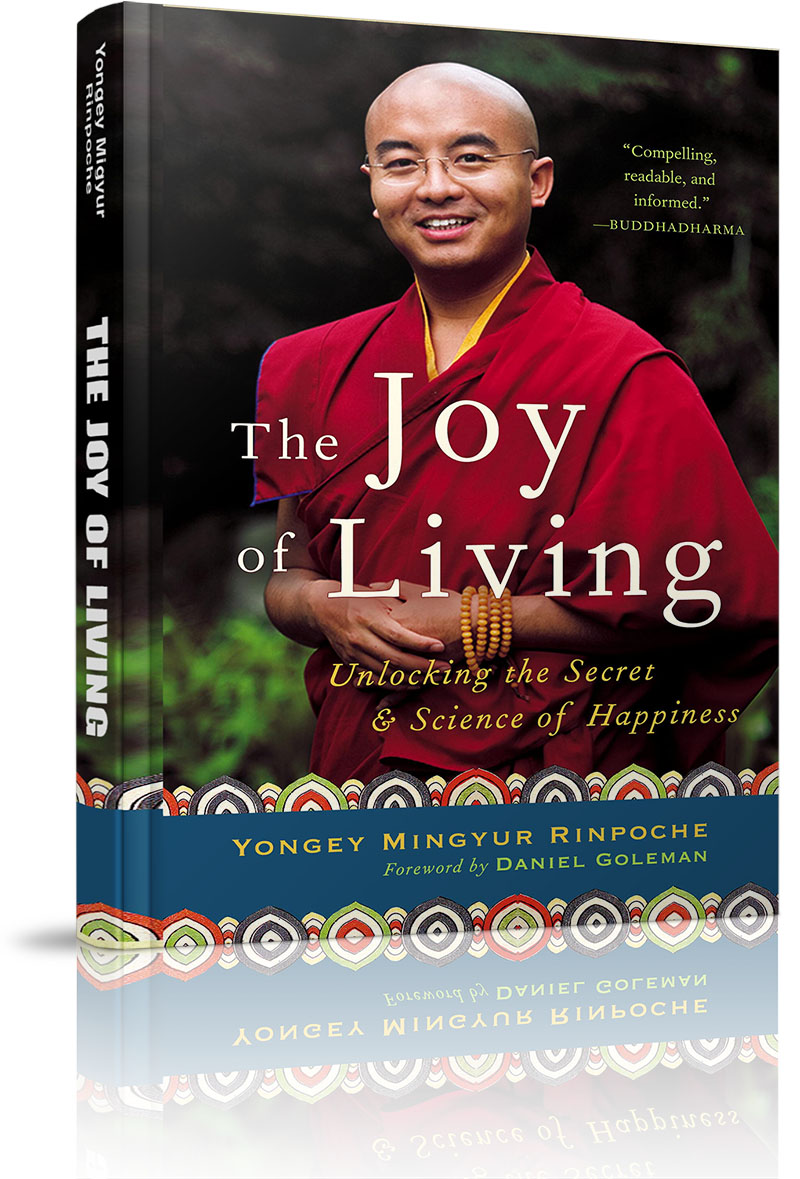

Trang chủ »» Danh mục »» SÁCH ANH NGỮ HOẶC SONG NGỮ ANH-VIỆT »» The Joy of Living »» 6. The Gift of Clarity »»

The Joy of Living

»» 6. The Gift of Clarity

Xem Mục lục

Xem Mục lục  Vietnamese || Đối chiếu song ngữ

Vietnamese || Đối chiếu song ngữ

- none

- Introduction

- Part One: The Ground - 1. The Journey Begins

- 2. The inner symphony

- 3. Beyond the mind, beyond the brain

- Emptiness: The reality beyond reality

- The relativity of perception

- »» 6. The Gift of Clarity

- 7. Compassion: Survival of the kindest

- 8. Why are we unhappy?

- Part Two: The Path - 9. Finding Your Balance

- 10. Simply resting: The first step

- 11. Next steps: Resting on objects

- 12. Working with thoughts and feelings

- 13. Compassion: Opening the heart of the mind

- 14. The how, when, and where of practice

- Part Three: The fruit - 15. Problems and Possibility

- 16. An inside job

- 17. The biology of happiness

- 18. Moving on

- none

- THE THIRD GYALWANG KARMAPA, Song of Karmapa: The Aspiration of the Mahamudra of True Meaning, translated by Erik Pema Kunsang

Although we compare emptiness to space as a way to understand the infinite nature of the mind, the analogy isn’t perfect. Space - at least as far as we know - isn’t conscious. From the Buddhist perspective, however, emptiness and awareness are indivisible. You can’t separate emptiness from awareness any more than you can separate wetness from water or heat from fire. Your real nature, in other words, is not only unlimited in its potential, but also completely aware.

This spontaneous awareness is known in Buddhist terms as clarity, or sometimes as the clear light of mind. It’s the cognizant aspect of the mind that allows us to recognize and distinguish the infinite variety of thoughts, feelings, sensations, and appearances that perpetually emerge out of emptiness. Clarity operates even when we’re not consciously attentive - for instance, when we suddenly think, I need to eat, I need to leave, I need to stay. Without this clear light of mind, we wouldn’t be able to think, feel, or perceive anything. We wouldn’t be able to recognize our own bodies, or the universe or anything that appears in it.

NATURAL AWARENESS

Appearances and mind exist like fire and heat.

- ORGYENPA, quoted in Mahamudra: The Ocean of Definitive Meaning, translated by Elizabeth M. Callahan

My teachers described this clear light of mind as self-illuminating - like the flame of a candle, which is both a source of illumination and illumination itself. Clarity is part of the mind from the beginning, a natural awareness. You can’t develop it the way, for instance, you develop muscles through physical exercise. The only thing you have to do is acknowledge it, simply notice the fact that you’re aware. The challenge, of course, is that clarity, or natural awareness, is so much a part of everyday experience that it’s hard to recognize. It’s like trying to see your eyelashes without using a mirror.

So how do you go about recognizing it?

According to the Buddha, you meditate - though not necessarily, in the way most people understand it.

The kind of meditation involved here is, again, a type of “non-meditation.” There’s no need to focus on or visualize anything. Some of my students call it ‘‘organic meditation - meditation without additives.”

As in other exercises my father taught me, the way to begin is to sit up straight, breathe normally, and gradually allow your mind to relax. “With your mind at rest,” he instructed those of us in his little teaching room in Nepal, “just allow yourself to become aware of all the thoughts, feelings, and sensations passing through it. And as you watch them pass, simply ask yourself, ‘Is there a difference between the mind and the thoughts that pass through it? Is there any difference between the thinker and the thoughts perceived by the thinker?’ Continue watching your thoughts with these questions in mind for about three minutes or so, and then stop.”

So there we all sat, some of us fidgeting, some of us tense, but all of us focused on watching our minds and asking ourselves whether there was any difference between thoughts and the thinker who thinks the thoughts.

Since I was just a child, and most of the other students were adults, I naturally thought they were doing a much better job than I was. But as I watched these thoughts about my own inadequacy pass through my mind, I remembered the instructions, and a funny thing happened. For just a moment, I glimpsed that the thoughts about not being as good as the other students were just thoughts, and the thoughts weren’t really fixed realities, but simply movements of the mind that was thinking them. Of course, as soon as I glimpsed that, the realization passed and I was back to comparing myself against the other students. But that brief moment of clarity was profound.

As my father explained after we’d finished, the point of the exercise was to recognize that there really is no difference between the mind that thinks and thoughts that come and go in the mind. The mind itself and the thoughts, emotions, and sensations that arise, abide, and disappear in the mind are equal expressions of emptiness - that is, the open-ended possibility for anything to occur. If the mind is not a “thing” but an event, then all the thoughts, feelings, and sensations that occur in what we think of as the mind are likewise events. As we begin to rest in the experience of mind and thoughts as inseparable, like two sides of the same coin, we begin to grasp the true meaning of clarity as an infinitely expansive state of awareness.

A lot of people think that meditation means achieving some unusually vivid state, completely unlike anything they’ve experienced before. They mentally squeeze themselves, thinking, I’ve got to attain a higher level of consciousness... I should be seeing something wonderful, like rainbow lights or images of pure realms... I should be glowing in the dark.

That’s called trying too hard, and believe me, I’ve done it, as have a lot of other people I’ve come to know over the years.

Not long ago, I met someone who was causing problems for himself by trying too hard. I was sitting in the Delhi airport waiting to board a plane for Europe, when a man approached me and asked if I was a Buddhist monk. I replied that I was. He then asked me if I knew how to meditate, and when I replied that I did, he asked, “What’s your experience like?”

“Fine,” I answered.

“You don’t find it difficult?”

“No,” I said, “not really.”

He shook his head and sighed. “Meditation is so hard for me,” he explained.

“After fifteen or twenty minutes, I start getting dizzy. And if I try to go on longer than that, I sometimes even throw up.”

I told him that it sounded to me as though he was too tense, and that he should maybe try to relax more when he practiced.

“No,” the man replied. “When I try to relax, I get even dizzier.”

His problem seemed strange, and because he appeared genuinely interested in finding a solution, I asked him to sit across from me and meditate while I just watched him. After he settled in the seat opposite me, his arms, legs, and chest stiffened dramatically. His eyes bulged; a terrible grimace spread across his face; his eyebrows shot upward; and even his ears seemed to pull away from his head. His body was so tense he started shaking.

Just watching him, I thought I might get dizzy myself, so I said, “Okay, please stop.”

He relaxed his muscles, the grimace vanished from his face, and his eyes, ears, and eyebrows returned to normal. Eagerly, he looked at me for advice.

“All right,” I said. “Now I’m going to meditate, while you watch me the way I watched you.”

I just sat in my seat as I normally do, with my spine straight, my muscles relaxed, my hands resting gently in my lap, and looking forward without any particular strain as I rested my mind with bare attention on the present moment. I watched the man looking at me from head to toe, toe to head, and head to toe again. Then I simply came out of meditation and told him that that was how I meditated.

After a moment he nodded slowly and said, “I think I get it.”

Just then it was announced that our plane was ready for boarding. Since he and I were seated in different sections of the plane, we boarded separately and I didn’t see him at all during the flight.

After we landed, I saw him again among the passengers disembarking from the plane. He waved, and as he approached me he said,

“You know, I tried practicing the way you showed me, and through the whole flight I was able to meditate without getting dizzy. I think I finally understand what it means to relax in meditation. Thank you so much!”

It’s certainly possible to have vivid experiences when you try too hard, but the more typical results can be grouped into three general types of experiences. The first is that the attempt to become aware of all the thoughts, feelings, and sensations rushing through your mind is simply exhausting, and as a result you may find your mind becoming tired or dull. The second is that the attempt to observe every thought, emotion, and sensation generates a sense of restlessness or agitation. The third is that you may discover that your mind goes completely blank: Every thought, emotion, feeling, or perception you observe passes so quickly that it simply eludes your awareness. In any of these cases, you might reasonably conclude that meditation isn’t the great experience you imagined it might be.

Actually, the essence of meditation practice is to let go of all your expectations about meditation. All the qualities of your natural mind - peace, openness, relaxation, and clarity - are present in your mind just as it is. You don’t have to do anything different. You don’t have to shift or change your awareness. All you have to do while observing your mind is to recognize the qualities it already has.

LIGHTING UP THE DARK

You cannot separate a lit area and a shaded area from one another, they are so close.

- TULKU URGYEN RINPOCHE, As It Is, Volume 1, translated by Erik Pema Kunsang

Learning to appreciate the clarity of the mind is a gradual process, just like developing an awareness of emptiness. First you get the main point, slowly grow more familiar with it, and then just continue training in recognition. Some texts actually compare this slow course of recognition to an old cow peeing - a nice, down-to-earth description that keeps us from thinking of the process as something terribly difficult or abstract. Unless, however, you’re a Tibetan nomad or happen to have been brought up on a farm, the comparison might not be immediately clear, so let me explain. An old cow doesn’t pee in one quick burst, but in a slow, steady stream. It may not start out as much and it doesn’t end quickly, either. In fact, the cow may walk several yards while in the process, continuing to graze. But when it’s over - what a relief!

Like emptiness, the true nature of clarity is impossible to define completely without turning it into some sort of concept that you can tuck away in a mental pocket, thinking, Okay, I get it, my mind is clear, now what? Clarity in its pure form has to be experienced. And when you experience it, there’s no “Now what?” You just get it.

If you think about the difficulty of trying to describe something that is essentially beyond description, you can probably understand something of the challenge the Buddha must have faced in trying to explain the nature of mind to his students - who were no doubt people just like ourselves, looking for clear-cut definitions that they could file away intellectually, making them feel momentarily proud that they were smarter and more sensitive than the rest of the world.

To avoid this trap, the Buddha, as we’ve seen, chose to describe the indescribable through metaphors and stories. In order to offer us a way to understand clarity in terms of everyday experience, he used the same analogy he used to describe emptiness, that of a dream.

He asked us to imagine the total darkness of sleep, with our eyes closed, the curtains shut, and our minds descending into a state of total blankness. Yet within this darkness, he explained, forms and experiences begin to appear. We encounter people - some familiar, others strangers. We may find ourselves in places we’ve known or places freshly imagined. The events we experience may be echoes of things we’ve experienced in waking life, or they may be completely new, never before imagined. In dreams, any and all experiences are possible, and the light that illumines and distinguishes the various people, places, and events within the darkness of sleep is an aspect of the pure clarity of mind.

The main difference between the dream example and true clarity is that even while dreaming, most of us still make a distinction between ourselves and others, and the places and events we experience. When we truly recognize clarity, we perceive no such distinction. Natural mind is indivisible. It’s not as if I’m experiencing clarity over here, and you’re experiencing clarity over there. Clarity, like emptiness, is infinite: It has no limits, no starting point and no end. The more deeply we examine our minds, the less possible it becomes to find a clear distinction between where our own mind ends and others’ begin. As this begins to happen, the sense of difference between “self” and “other” gives way to a gentler and more fluid sense of identification with other beings and with the world around us. And it’s through this sense of identification that we start to recognize that the world may not be such a scary place after all: that enemies aren’t enemies but people like ourselves, longing for happiness and seeking it the best way they know how, and that everyone possesses the insight, the wisdom, and the understanding to see past apparent differences and discover solutions that benefit not just ourselves but everyone around us.

APPEARANCE AND ILLUSION

Seeing the meaningful as meaningful, and the meaningless as meaningless, one is capable of genuine understanding.

- The Dhammapada, translated by Eknath Easwaran

The mind is like a stage magician, however. It can make us see things that aren’t really there. Most of us are enthralled by the illusions our minds create, and we actually encourage ourselves to produce more and more outrageous fantasies. The sheer drama becomes addictive, producing what some of my students call an “adrenaline rush” or a “high” that makes us, or our problems, feel bigger than life - even when the situation that produces it is scary.

Just as we applaud the magician’s trick of pulling a rabbit out of a hat, we watch horror movies, read suspense novels, get involved in difficult relationships, and fight with our bosses and coworkers. In a strange way - perhaps related to the most ancient, reptilian layer of the brain - we actually enjoy the tension these experiences provide. By strengthening our sense of “me” against “them,” they confirm our sense of individuality - which, as we saw in the last chapter, is itself actually an appearance, lacking inherent reality.

Some cognitive psychologists I’ve spoken with have compared the human mind to a movie projector. Just as a projector casts images onto a screen, the mind projects sensory phenomena onto a type of cognitive screen - a context that we think of as the “external world” - while projecting thoughts, feelings, and sensations onto another type of screen or context that we refer to as our inner world, or “me.”

That’s getting close to a Buddhist perspective on absolute and relative reality. Absolute reality is emptiness, a condition in which perceptions are intuitively recognized as an infinite and transitory flow of possible experiences. When you begin to recognize perceptions as nothing more than fleeting, circumstantial events, they don’t weigh as heavily on you, and the whole dualistic structure of “self and “other” begins to soften. Relative reality is the sum of experiences arising from the mistaken idea that whatever you perceive is real in and of itself.

The habit of thinking that things exist “out there” in the world or “in here” is hard to give up, though. It means letting go of all the illusions you cherish, and recognizing that everything you project, everything you think of as “other,” is in fact a spontaneous expression of your own mind. It means letting go of ideas about reality and instead experiencing the flow of reality as it is. At the same time, you don’t have to completely disengage from your perceptions. You don’t have to isolate yourself in a cave or mountain retreat. You can enjoy your perceptions without actively engaging them, looking at them in the same way you’d look at the objects you’d experience in a dream. You can actually begin to marvel at the variety of experiences that present themselves to you.

Through recognizing the distinction between appearance and illusion, you give yourself permission to acknowledge that some of your perceptions might be wrong or biased, that your ideas of how things ought to be may have solidified to the degree that you can’t see any other point of view but your own.

When I began to recognize the emptiness and clarity of my own mind, my life became richer and more vivid in ways I never could have imagined. Once I shed my ideas about how things should be, I became free to respond to my experience exactly as it was and exactly as I was, right there, right then.

THE UNION OF CLARITY AND EMPTINESS

Our true nature has inexhaustible properties.

- MAITREYA, The Mahayana Uttaratantra Shastra, translated by Rosemarie Fuchs

It’s said that the Buddha taught 84,000 methods to help people at various levels of understanding recognize the power of the mind. I haven’t studied them all, so I can’t swear that the number is exact. He may have taught 83,999 or 84,001. The essence of his teachings, however, can be reduced to a single point: The mind is the source of all experience, and by changing the direction of the mind, we can change the quality of everything we experience. When you transform your mind, everything you experience is transformed. It’s like putting on a pair of yellow glasses: Suddenly, everything you see is yellow. If you put on a pair of green glasses, everything you see is green.

Clarity, in this sense, may be understood as the creative aspect of mind. Everything you perceive, you perceive through the power of your awareness. There are truly no limits to the creative ability of your mind. This creative aspect is the natural consequence of the union of emptiness and clarity. It’s known in Tibetan as magakpa, or “unimpededness.” Sometimes magakpa is translated as “power” or “ability,” but the meaning is the same: the freedom of the mind to experience anything and everything whatsoever.

To the extent that you can acknowledge the true power of your mind, you can begin to exercise more control over your experience. Pain, sadness, fear, anxiety, and all other forms of suffering no longer disrupt your life as forcefully as they used to. Experiences that once seemed to be obstacles become opportunities for deepening your understanding of the mind’s unimpeded nature.

Everyone experiences sensations of pain and pleasure throughout their lives. Most of these sensations appear to have some sort of a physical basis. Having a massage, eating good food, or taking a warm bath would generally be considered physically pleasant experiences. Burning a finger, getting an injection, or being stuck in traffic on a hot day in a car without air-conditioning would be considered physically unpleasant. Actually, though, whether you experience these things as painful or pleasurable doesn’t depend on the physical sensations in themselves, but on your perception of them.

For example, some people can’t stand feeling hot or cold. They say they’ll die if they have to go outside in hot weather. Even a few drops of sweat can make them feel extremely uncomfortable. In winter, they can’t bear even a few flakes of snow on their heads. But if a doctor they trust tells them that spending ten minutes every day in a sauna will improve their physical condition, they’ll often follow the advice, seeking out and even paying for an experience they previously couldn’t stand. They’ll sit in the sauna thinking, How nice, I’m sweating! This is really good! They do this because they’ve allowed themselves to shift their mental perception about being hot and sweaty. Heat and sweat are just phenomena to which they’ve assigned different meanings. And if the doctor further tells them that a cold shower after the sauna will improve their circulation, they learn to accept the cold, and even come to consider it refreshing.

Psychologists often refer to this sort of transformation as “cognitive restructuring.” Through applying intention as well as attention to an experience, a person is able to shift the meaning of an experience from a painful or intolerable context to one that is tolerable or pleasant. Over time, cognitive restructuring establishes new neuronal pathways in the brain, particularly in the limbic region, where most sensations of pain and pleasure are recognized and processed.

If our perceptions really are mental constructs conditioned by past experiences and present expectations, then what we focus on and how we focus become important factors in determining our experience. And the more deeply we believe something is true, the more likely it will become true in terms of our experience. So if we believe we’re weak, stupid, or incompetent, then no matter what our real qualities are, and no matter how differently our friends and associates see us, we’ll experience ourselves as weak, stupid, or incompetent.

What happens when you begin to recognize your experiences as your own projections? What happens when you begin to lose your fear of the people around you and conditions you used to dread? Well, from one point of view - nothing. From another point of view - everything.

MUA THỈNH KINH SÁCH PHẬT HỌC

DO NXB LIÊN PHẬT HỘI PHÁT HÀNH

Mua sách qua Amazon sẽ được gửi đến tận nhà - trên toàn nước Mỹ, Canada, Âu châu và Úc châu.

Quý vị đang truy cập từ IP 216.73.216.44, 147.243.245.203 và chưa ghi danh hoặc đăng nhập trên máy tính này. Nếu là thành viên, quý vị chỉ cần đăng nhập một lần duy nhất trên thiết bị truy cập, bằng email và mật khẩu đã chọn.

Chúng tôi khuyến khích việc ghi danh thành viên ,để thuận tiện trong việc chia sẻ thông tin, chia sẻ kinh nghiệm sống giữa các thành viên, đồng thời quý vị cũng sẽ nhận được sự hỗ trợ kỹ thuật từ Ban Quản Trị trong quá trình sử dụng website này.

Việc ghi danh là hoàn toàn miễn phí và tự nguyện.

Ghi danh hoặc đăng nhập

... ...

Trang chủ

Trang chủ