Bạn có biết là những người thành đạt hơn bạn vẫn đang cố gắng nhiều hơn cả bạn?Sưu tầm

Nỗ lực mang đến hạnh phúc cho người khác sẽ nâng cao chính bản thân ta. (An effort made for the happiness of others lifts above ourselves.)Lydia M. Child

Ai sống quán bất tịnh, khéo hộ trì các căn, ăn uống có tiết độ, có lòng tin, tinh cần, ma không uy hiếp được, như núi đá, trước gió.Kinh Pháp Cú (Kệ số 8)

Kẻ bi quan than phiền về hướng gió, người lạc quan chờ đợi gió đổi chiều, còn người thực tế thì điều chỉnh cánh buồm. (The pessimist complains about the wind; the optimist expects it to change; the realist adjusts the sails.)William Arthur Ward

Phải làm rất nhiều việc tốt để có được danh thơm tiếng tốt, nhưng chỉ một việc xấu sẽ hủy hoại tất cả. (It takes many good deeds to build a good reputation, and only one bad one to lose it.)Benjamin Franklin

Ngủ dậy muộn là hoang phí một ngày;tuổi trẻ không nỗ lực học tập là hoang phí một đời.Sưu tầm

Cơ hội thành công thực sự nằm ở con người chứ không ở công việc. (The real opportunity for success lies within the person and not in the job. )Zig Ziglar

Mục đích chính của chúng ta trong cuộc đời này là giúp đỡ người khác. Và nếu bạn không thể giúp đỡ người khác thì ít nhất cũng đừng làm họ tổn thương. (Our prime purpose in this life is to help others. And if you can't help them, at least don't hurt them.)Đức Đạt-lai Lạt-ma XIV

Điều quan trọng không phải vị trí ta đang đứng mà là ở hướng ta đang đi.Sưu tầm

Mỗi ngày khi thức dậy, hãy nghĩ rằng hôm nay ta may mắn còn được sống. Ta có cuộc sống con người quý giá nên sẽ không phí phạm cuộc sống này.Đức Đạt-lai Lạt-ma XIV

Bậc trí bảo vệ thân, bảo vệ luôn lời nói, bảo vệ cả tâm tư, ba nghiệp khéo bảo vệ.Kinh Pháp Cú (Kệ số 234)

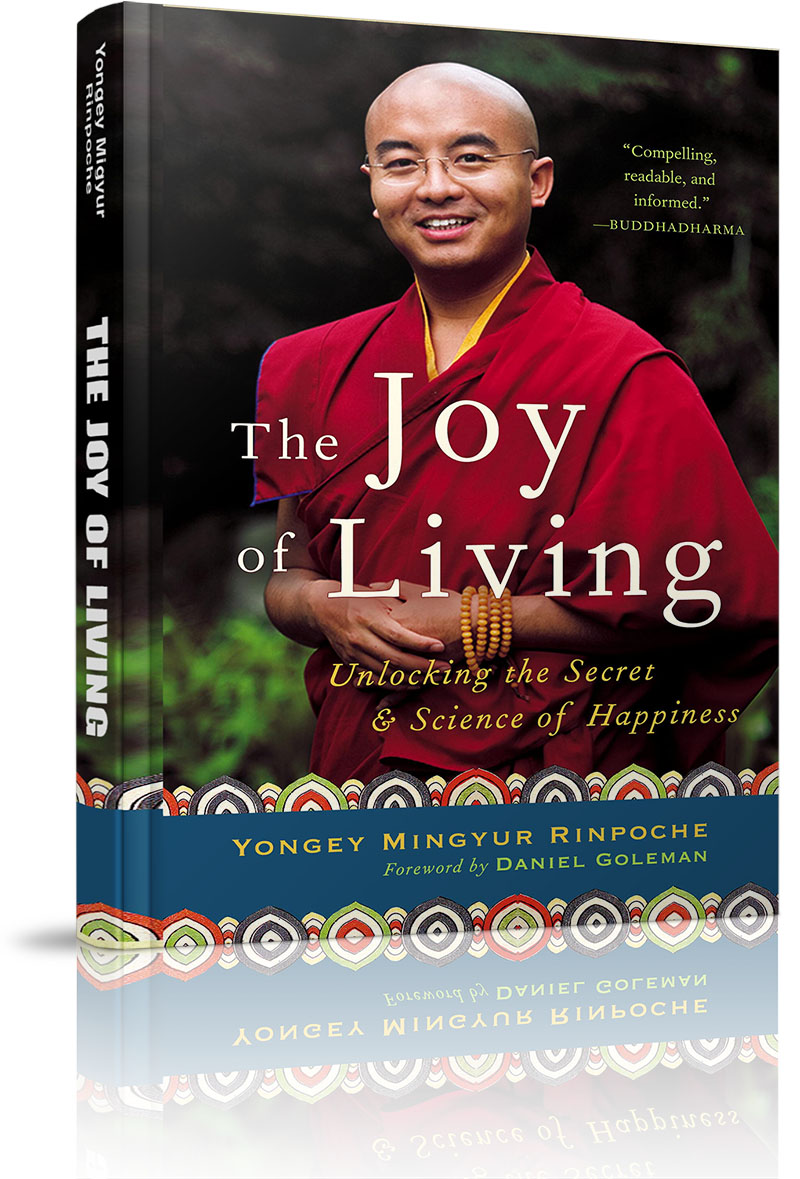

Trang chủ »» Danh mục »» SÁCH ANH NGỮ HOẶC SONG NGỮ ANH-VIỆT »» The Joy of Living »» Part Three: The fruit - 15. Problems and Possibility »»

The Joy of Living

»» Part Three: The fruit - 15. Problems and Possibility

Xem Mục lục

Xem Mục lục  Vietnamese || Đối chiếu song ngữ

Vietnamese || Đối chiếu song ngữ

- none

- Introduction

- Part One: The Ground - 1. The Journey Begins

- 2. The inner symphony

- 3. Beyond the mind, beyond the brain

- Emptiness: The reality beyond reality

- The relativity of perception

- 6. The Gift of Clarity

- 7. Compassion: Survival of the kindest

- 8. Why are we unhappy?

- Part Two: The Path - 9. Finding Your Balance

- 10. Simply resting: The first step

- 11. Next steps: Resting on objects

- 12. Working with thoughts and feelings

- 13. Compassion: Opening the heart of the mind

- 14. The how, when, and where of practice

- »» Part Three: The fruit - 15. Problems and Possibility

- 16. An inside job

- 17. The biology of happiness

- 18. Moving on

- none

- JEROME KAGAN, Three Seductive Ideas

At the beginning our mind is not able to remain stable and rest for very long. However, with perseverance and consistency, calm and stability gradually develop.

- BOKAR RINPOCHE, Meditation: Advice to Beginners, translated by Christiane Buchet

Wonderful experiences can occur when you rest your mind in meditation. Sometimes it takes a while for these experiences to occur; sometimes they happen the very first time you sit down to practice. The most common of these experiences are bliss, clarity, and nonconceptuality.

Bliss, in the way it was explained to me, is a feeling of undiluted happiness, comfort, and lightness in both the mind and the body. As this experience grows stronger, it seems as if everything you see is made of love. Even experiences of physical pain become very light and hardly noticeable at all.

Clarity is a sense of being able to see into the nature of things as though all reality were a landscape lit up on a brilliantly sunny day without clouds. Everything appears distinct and everything makes sense. Even disturbing thoughts and emotions have their place in this brilliant landscape.

Nonconceptuality is an experience of the total openness of your mind. Your awareness is direct and unclouded by conceptual distinctions such as “I” or “other,” subjects and objects, or any other form of limitation. It’s an experience of pure consciousness as infinite as space, without beginning, middle, or end. It’s like becoming awake within a dream and recognizing that everything experienced in the dream isn’t separate from the mind of the dreamer.

Very often, though, what I hear from people who are just starting out to meditate is that they sit there and nothing happens. Sometimes they feel a very brief, very slight sense of calmness. But in most cases they don’t feel any different from the way they did before they sat down or after they got up. That can be a real disappointment.

Some people, furthermore, feel a sense of disorientation, as though their familiar world of thoughts, emotions, and sensations has tilted slightly - which may be pleasant or unpleasant.

As I’ve mentioned before, whether you experience bliss, clarity, disorientation, or nothing at all, the intention to meditate is -more important than what happens when you meditate. Since mindfulness is already present, just making the effort to connect with it will develop your awareness of it. If you keep practicing, gradually you might feel a little something, a sense of calmness or peace of mind that is slightly different from your ordinary state of mind. When you begin to experience that, you’ll intuitively understand the difference between the distracted mind and the undistracted mind of meditation.

In the beginning, most of us aren’t able to rest our minds in bare awareness for a very long time at all. If you can rest for only a very short time, that’s fine. Just follow the instruction given earlier to repeat that short period of relaxation many times over in any given session. Even resting the mind for the time it takes you to breathe in and breathe out is enormously useful. Just do that again and again and again.

Conditions are always changing, and real peace lies in the ability to adapt to the changes. For example, suppose you’re sitting there focusing calmly on your breathing and your upstairs neighbor starts vacuuming, or a dog starts barking somewhere in the vicinity. Maybe your back or your legs start to hurt, or maybe you feel an itch. Or maybe the memory of a fight you had the other day pops into your head for no apparent reason. These things happen all the time - and that’s another reason why the Buddha taught so many different methods of meditation.

When distractions of this sort occur, just make them a part of your practice. Join your awareness to the distraction. If your breathing practice is interrupted by the noise of a dog barking or a vacuum cleaner, switch to sound meditation, resting your attention on the noise. If you feel pain in your back or legs, bring your attention to the mind that feels the pain. If you have an itch, go ahead and scratch it. If you ever have a chance to sit in a Buddhist shrine room while a lecture or a chanting practice is taking place, you’ll undoubtedly see the monks restlessly scratching themselves, shifting on their cushions, or coughing. But, chances are, if they’ve taken their training seriously enough, they’re shifting around, scratching, and so on mindfully - bringing their attention to the sensation of the itch, the sensation of scratching it, and the relief they feel when they’re done scratching.

If you’re distracted by strong emotions, you can try focusing, as was taught earlier, on the mind that experiences the emotion. Or you might try switching to tonglen practice, using whatever you’re feeling - anger, sadness, jealousy, desire - as the basis for the practice.

At the opposite end of the scale, a number of people I know find their minds getting foggy or sleepy when they practice. It’s such an effort just to keep their eyes open and their attention focused on what they’re doing. The thought of giving up for the day and flopping down in bed seems very tempting.

There are a couple of ways to deal with this situation. One, which is simply a variation on being mindful of physical sensations, is to rest your attention on the sensation of dullness or sleepiness itself. In other words, use your dullness rather than being used by it. If you can’t sit up, just lie down while keeping your spine as straight as possible.

Another remedy is simply to raise your eyes so that you’re gazing upward. You don’t have to lift your head or your chin, just turn your gaze upward. That often has the effect of waking your mind. Lowering your gaze, meanwhile, can have a calming effect when your mind is agitated.

If none of the remedies for dullness or distraction work, I usually recommend to students that they just stop for a while and take a break. Go for a walk, take care of something around the house, exercise, read a book, or work in the garden. There’s no sense in trying to make yourself meditate if your mind and body aren’t willing to cooperate. If you try to hammer away at your resistance, eventually you’ll get frustrated with the whole idea of meditation and decide to chuck it in favor of achieving happiness through some temporary attraction. At those times, all those channels available through your satellite dish or cable TV box look pretty promising.

PROGRESSIVE STAGES OF MEDITATION PRACTICE

Allow the water [of mind] clouded by thoughts to clear.

- TILOPA, Ganges Mahamudra, translated by Elizabeth M. Callahan

When I first began meditating, I was horrified to find myself experiencing more thoughts, feelings, and sensations than I had before I began practicing. It seemed that my mind was becoming more agitated rather than more peaceful. “Don’t worry,” my teachers told me. “Your mind isn’t getting worse. Actually, what’s happening is that you’re simply becoming more aware of activity that has been going on all the time without your noticing it.”

The Waterfall Experience

They explained this experience through the analogue of a waterfall suddenly swollen by a spring thaw. As melting snow floods down from the mountains, they told me, all sorts of stuff gets stirred up. There might be hundreds of rocks, stones, and other elements flowing through the water, but it’s impossible to see them all because the water is rushing by so quickly, shaking up all sorts of debris that clouds the water; and it’s very easy to become distracted by all that mental and emotional debris. They taught me a short prayer known as the Dorje Chang Tungma, which I found very helpful when my mind seemed overwhelmed by thoughts, emotions, and sensations. Part of it, roughly translated, goes like this:

The body of meditation, it’s said, is nondistraction.

Whatever thoughts are perceived by the mind are nothing in themselves.

Help this meditator who rests naturally in the essence

of whatever thoughts arise to rest in the mind as it naturally is.

In working with many students around the world, I’ve observed that the “waterfall” experience is often the first one people encounter when they begin to meditate. There are actually several common reactions to this experience, and I’ve experienced them all. In a sense, I consider myself fortunate, because having experienced these stages has enabled me to develop greater empathy toward my students. At the time, though, the waterfall seemed like a terrible ordeal.

The first variation involves trying to stop the waterfall by deliberately trying to block thoughts, feelings, and sensations in order to experience a sense of calmness, openness, and peace. This attempt to block experience is counterproductive, because it creates a sense of mental or emotional tightness that ultimately manifests as a physical strain, especially in the upper body: Your eyes roll upward, your ears become taut, and your neck and shoulders become abnormally tense. I tend to think of this phase of practice as “rainbow-like” meditation, because the calmness after blocking the flow of the waterfall is as illusory and transient as a rainbow.

Once you let go of trying to impose an artificial sense of calmness, you’ll find yourself confronting the “raw” waterfall experience, in which your mind is carried away by various thoughts, feelings, and sensations you may previously have tried to block. This is generally the kind of “Oops” experience described earlier in Part Two - in which you start trying to observe your thoughts, feelings, and sensations, and then get carried away by them. You recognize you’ve been carried away, and you try to force yourself back to simply observing what’s going on in your mind. I call this the “hook” form of meditation, in which you try to hook your experiences, and feel some regret if you allow yourself to be carried away by them instead.

There are two ways to deal with the “hook” situation. If your regret over letting yourself be carried away by distractions is really strong, then just let your mind rest gently in the experience of regret. Otherwise, let go of the distractions and rest your awareness in your present experience. You might, for example, try bringing attention to your physical sensations: Perhaps your head is a little bit warm, your heart is beating a little faster, or your neck or shoulders are a little tense. Just rest your awareness on these or other experiences that occur in the present moment. You might also try simply resting with bare attention - as discussed in Parts One and Two - in the rush of the waterfall itself.

However you deal with it, the waterfall experience provides an important lesson in letting go of preconceived ideas about meditation. The expectations you bring to meditation practice are often the greatest obstacles you will encounter. The important point is to allow yourself simply to be aware of whatever is going on in your mind as it is.

Another possibility is that experiences come and go too quickly for you to recognize them. It’s as though each thought, feeling, or sensation is a drop of water that falls into a large pool and is immediately absorbed. That’s actually a very good experience. It’s a kind of objectless meditation, the best form of calm-abiding practice. So if you can’t catch every “drop,” don’t blame yourself - congratulate yourself, because you’ve spontaneously entered a state of meditation that most people find hard to reach.

After a little bit of practice, you’ll find that the rush of thoughts, emotions, and so on begins to slow, and it becomes possible to distinguish your experiences more clearly. They were there all the time, but as in the case of a real waterfall, in which the rush of water stirs up so much dirt and sediment, you just couldn’t see them. Likewise, as the habitual tendencies and distractions that normally cloud the mind begin to settle through meditation, you’ll begin to see the activity that has been going on all the time just below the level of ordinary awareness.

Still, you might not be able to observe each thought, feeling, or perception as it passes, but only catch a fleeting glimpse of it - rather like the experience of having just missed a bus, as described earlier. That’s okay, too. That sensation of just having missed observing a thought or feeling is a sign of progress, an indication that your mind is sharpening itself to catch traces of movement, the way a detective begins to notice clues.

As you keep practicing, you’ll find that you’re able to become aware of each experience more clearly as it occurs. The analogy my teachers provided to describe this phenomenon was that of a flag waving in a strong wind. The flag shifts and moves constantly, according to the direction of the wind. The movements of the flag are like the events whipping through your mind, while the flagpole is like your natural awareness: straight and steady, never shifting, anchored to the ground. It doesn’t move, no matter how strong the wind that whips the flag in one direction or another.

The River Experience

Gradually, as you continue to practice, you’ll inevitably find yourself able to clearly distinguish the movements of thoughts, emotions, and sensations through your mind. At this point you’ve begun to shift from the “waterfall” experience to what my teachers called the “river” experience, in which things are still moving, but more slowly and gently. One of the first signs that you’ve entered the river phase of meditation experience is that you’ll find yourself occasionally entering a state of meditative awareness without much effort, naturally joining your awareness with whatever is going on inside or around you. And when you sit in formal practice, you’ll have clearer experiences of bliss, clarity, and nonconceptuality.

Sometimes the three experiences occur simultaneously, and sometimes one experience is stronger than the other two. You may feel that your body is becoming lighter and less tense. You may find that your perceptions are becoming clearer and, in a way, more “transparent,” in that they don’t seem so heavy or oppressive as they may have felt in the past. Thoughts and feelings don’t seem so powerful anymore; they become infused with the “juice” of meditative awareness, appearing more like passing impressions than absolute facts. When you “enter the river,” you’ll find your mind becoming calmer. You’ll find yourself not taking its movements so seriously, and as a result you’ll find yourself spontaneously experiencing a greater sense of confidence and openness, which won’t be shaken by who you meet, what you experience, or where you go. Even though such experiences may come and go, you will begin to sense the beauty of the world around you.

Once that starts to happen, you’ll also begin to discern tiny gaps between experiences. At first the gaps will be very short - just fleeting glimpses of nonconceptuality or nonexperience. But over time, as your mind becomes calmer, the gaps will become longer and longer. This is really the heart of shinay practice: the ability to notice and rest in the gaps between thoughts, emotions, and other mental events.

The Lake Experience

During the “river” experience, your mind may still have its ups and downs. When you reach the next stage, which my teachers called the “lake” experience, your mind begins to feel very smooth, wide, and open, like a lake without waves. You find yourself genuinely happy, without any ups and downs. You’re full of confidence, stable, and you experience a more or less continuous state of meditative awareness, even while sleeping. You may still experience problems in your life - negative thoughts, strong emotions, and so on - but instead of being obstacles, they become further opportunities to deepen your meditative awareness, the way a runner uses the challenge of going half a mile farther to break through a “wall” of resistance and achieve even greater strength and ability.

At the same time, your body begins to feel the lightness of bliss, and your clarity improves so that all your perceptions begin to take on a sharper, almost transparent quality, like reflections in a mirror. While the crazy monkey mind may still pose a few problems during the river phase of experience, when you reach the lake stage, the crazy monkey has retired.

A traditional Buddhist analogy for progressing through these three stages is a lotus rising from the mud. A lotus begins to grow from the mud and sediment at the bottom of a lake or pond, but by the time the flower blooms at the surface, it bears no trace of mud; in fact, the petals actually appear to repel filth. In the same way, when your mind blossoms into the lake experience, you have no trace of clinging or grasping, none of the problems associated with samsara. You might even develop, as did the great masters of old, heightened powers of perception, such as clairvoyance or mental telepathy. If you do have these experiences, though, it’s best not to boast about them or mention them to anyone but your teacher or very close students of your teacher.

In the Buddhist tradition, people don’t talk much about their own experiences and realizations, mostly because such boasting tends to increase one’s own sense of pride and can lead to misuse of the experiences to gain worldly power or influence over other people, which is harmful to oneself and to others. For this reason, training in meditation involves a vow or a commitment - known in Sanskrit as samaya - not to misuse the abilities gained through meditation practice: a vow similar to treaties not to misuse nuclear arms. The consequence of breaking this commitment is the loss of whatever realizations and abilities one has attained through practice.

MISTAKING EXPERIENCE FOR REALIZATION 431

Give up whatever you’re attached to.

- THE NINTH GYALWANG KARMAPA,

Mahamudra: The Ocean of Definitive Meaning, translated by Elizabeth M. Callahan

Although the lake experience may be considered the crown of shinay practice, it is not in itself realization or full enlightenment. It’s an important step along the way, but not the final one. Realization is the full recognition of your Buddha nature, the basis of samsara and nirvana: free from thoughts, emotions, and the phenomenal experiences of sense consciousness and mental consciousness; free from dualistic experiences of self and other, subject and object; infinite in scope, wisdom, compassion, and ability.

My father once told a story about a time when he was still living in Tibet. One of his students, a monk, went up to a mountain cave to practice. One day the monk sent my father an urgent message to come visit him. When my father arrived, the monk excitedly told him, “I’ve become totally enlightened. I can fly. I know it. But, since you’re my teacher, I need your permission.”

My father recognized that the monk had merely had a glimpse - an experience - of his true nature, and told him quite bluntly, “Forget about it. You can’t fly.”

“No, no,” the monk excitedly replied. “If I jump from the top of the cave...”

“No,” my father interrupted.

They argued back and forth like that for a long while, until the monk finally broke down and said, “Well, if you say so, I won’t try.”

Since it was approaching noon, the monk offered my father lunch. After serving my father, the monk left the cave, and quite soon afterward, my father heard a strange noise - a kind of BLUMP - and then, from far below the cave, came a wail: “Please help me! I’ve broken my leg!”

My father climbed down to where the monk lay, and said, “You told me you were enlightened. Where is your experience now?”

“Forget about my experience!” the monk cried. “I’m in pain!”

Compassionate as always, my father carried the monk to his cave, splinted his leg, and gave him some Tibetan medicine to help heal his injury. But it was a lesson the monk never forgot.

Like my father, my other teachers were always careful to point out the distinction between momentary experience and true realization. Experience is always changing, like the movement of clouds against the sky. Realization - the stable awareness of the true nature of your mind - is like the sky itself, an unchanging background against which shifting experiences occur.

In order to achieve realization, the important thing is to allow your practice to evolve gradually, beginning with very short periods, several times a day. The incremental experiences of calmness, serenity, and clarity you experience during these short periods will inspire you, very naturally, to extend your practice for longer periods. Don’t force yourself to meditate when you’re too tired or too distracted. Don’t avoid practice when the small, still voice inside your mind tells you it’s time to focus.

It’s also important to let go of any sensations of bliss, clarity, or non-conceptuality you may experience. Bliss, clarity, and nonconceptuality are all very nice experiences, and are clearly signs of having made a profound connection with the true nature of your mind. But there is a temptation, when such experiences occur, to hold on to them tightly and make them last. It’s okay to remember these experiences and appreciate them, but if you try to hang on to them or repeat them, you’ll eventually end up feeling disappointed and frustrated. I know, because I’ve felt the same temptation myself, and I’ve experienced the frustration when I gave in to the temptation. Each flash of bliss, clarity, or nonconceptuality is a spontaneous experience of the mind as it is at that particular moment.

When you try to hold on to an experience like bliss or clarity, the experience loses its living, spontaneous quality; it becomes a concept, a dead experience. No matter how hard you try to make it last, it gradually fades. If you try to reproduce it later, you may get a taste of what you felt, but it will only be a memory, not the direct experience itself.

The most important lesson I learned was to avoid becoming attached to my positive experience if it was peaceful. As with every mental experience, bliss, clarity, and nonconceptuality spontaneously come and go. You didn’t create them, you didn’t cause them, and you can’t control them. They are simply natural qualities of your mind. I was taught that when such very positive experiences occur to stop right there, before the sensations dissipate. Contrary to my expectations, when I stopped practicing as soon as bliss, clarity, or some other wonderful experience occurred, the effects actually lasted much longer than when I tried to hang on to them. I also found that I was much more eager to meditate the next time I was supposed to practice.

Even more important, I discovered that ending my meditation practice at the point at which I experienced something of bliss, clarity, or nonconceptuality was a great exercise in learning to let go of the habit of dzinpa, or grasping. Grasping or clinging too tightly to a wonderful experience is the one real danger of meditation, because it’s so easy to think that this wonderful experience is a sign of realization. But in most cases it’s just a passing phase, a glimpse of the true nature of the mind, as easily obscured as when clouds obscure the sun. Once that brief moment of pure awareness has passed, you have to deal with the ordinary conditions of dullness, distraction, or agitation that confront the mind. And you gain greater strength and progress through working with these conditions than by trying to cling to experiences of bliss, clarity, or nonconceptuality.

Let your own experience serve as your guide and inspiration. Let yourself enjoy the view as you travel along the path. The view is your own mind, and because your mind is already enlightened, if you take the opportunity to rest awhile along the journey, eventually you’ll realize that the place you want to reach is the place you already are.

TỪ ĐIỂN HỮU ÍCH CHO NGƯỜI HỌC TIẾNG ANH

DO NXB LIÊN PHẬT HỘI PHÁT HÀNH

Mua sách qua Amazon sẽ được gửi đến tận nhà - trên toàn nước Mỹ, Canada, Âu châu và Úc châu.

Quý vị đang truy cập từ IP 216.73.216.34 và chưa ghi danh hoặc đăng nhập trên máy tính này. Nếu là thành viên, quý vị chỉ cần đăng nhập một lần duy nhất trên thiết bị truy cập, bằng email và mật khẩu đã chọn.

Chúng tôi khuyến khích việc ghi danh thành viên ,để thuận tiện trong việc chia sẻ thông tin, chia sẻ kinh nghiệm sống giữa các thành viên, đồng thời quý vị cũng sẽ nhận được sự hỗ trợ kỹ thuật từ Ban Quản Trị trong quá trình sử dụng website này.

Việc ghi danh là hoàn toàn miễn phí và tự nguyện.

Ghi danh hoặc đăng nhập

... ...

Trang chủ

Trang chủ