Mặc áo cà sa mà không rời bỏ cấu uế, không thành thật khắc kỷ, thà chẳng mặc còn hơn.Kinh Pháp cú (Kệ số 9)

Điều người khác nghĩ về bạn là bất ổn của họ, đừng nhận lấy về mình. (The opinion which other people have of you is their problem, not yours. )Elisabeth Kubler-Ross

Hầu hết mọi người đều cho rằng sự thông minh tạo nên một nhà khoa học lớn. Nhưng họ đã lầm, chính nhân cách mới làm nên điều đó. (Most people say that it is the intellect which makes a great scientist. They are wrong: it is character.)Albert Einstein

Thành công không được quyết định bởi sự thông minh tài giỏi, mà chính là ở khả năng vượt qua chướng ngại.Sưu tầm

Tinh cần giữa phóng dật, tỉnh thức giữa quần mê.Người trí như ngựa phi, bỏ sau con ngựa hèn.Kính Pháp Cú (Kệ số 29)

Hành động thiếu tri thức là nguy hiểm, tri thức mà không hành động là vô ích. (Action without knowledge is dangerous, knowledge without action is useless. )Walter Evert Myer

Những chướng ngại không thể làm cho bạn dừng lại. Nếu gặp phải một bức tường, đừng quay lại và bỏ cuộc, hãy tìm cách trèo lên, vượt qua hoặc đi vòng qua nó. (Obstacles don’t have to stop you. If you run into a wall, don’t turn around and give up. Figure out how to climb it, go through it, or work around it. )Michael Jordon

Cơ hội thành công thực sự nằm ở con người chứ không ở công việc. (The real opportunity for success lies within the person and not in the job. )Zig Ziglar

Học vấn của một người là những gì còn lại sau khi đã quên đi những gì được học ở trường lớp. (Education is what remains after one has forgotten what one has learned in school.)Albert Einstein

Việc người khác ca ngợi bạn quá hơn sự thật tự nó không gây hại, nhưng thường sẽ khiến cho bạn tự nghĩ về mình quá hơn sự thật, và đó là khi tai họa bắt đầu.Rộng Mở Tâm Hồn

Nếu muốn người khác được hạnh phúc, hãy thực tập từ bi. Nếu muốn chính mình được hạnh phúc, hãy thực tập từ bi.Đức Đạt-lai Lạt-ma XIV

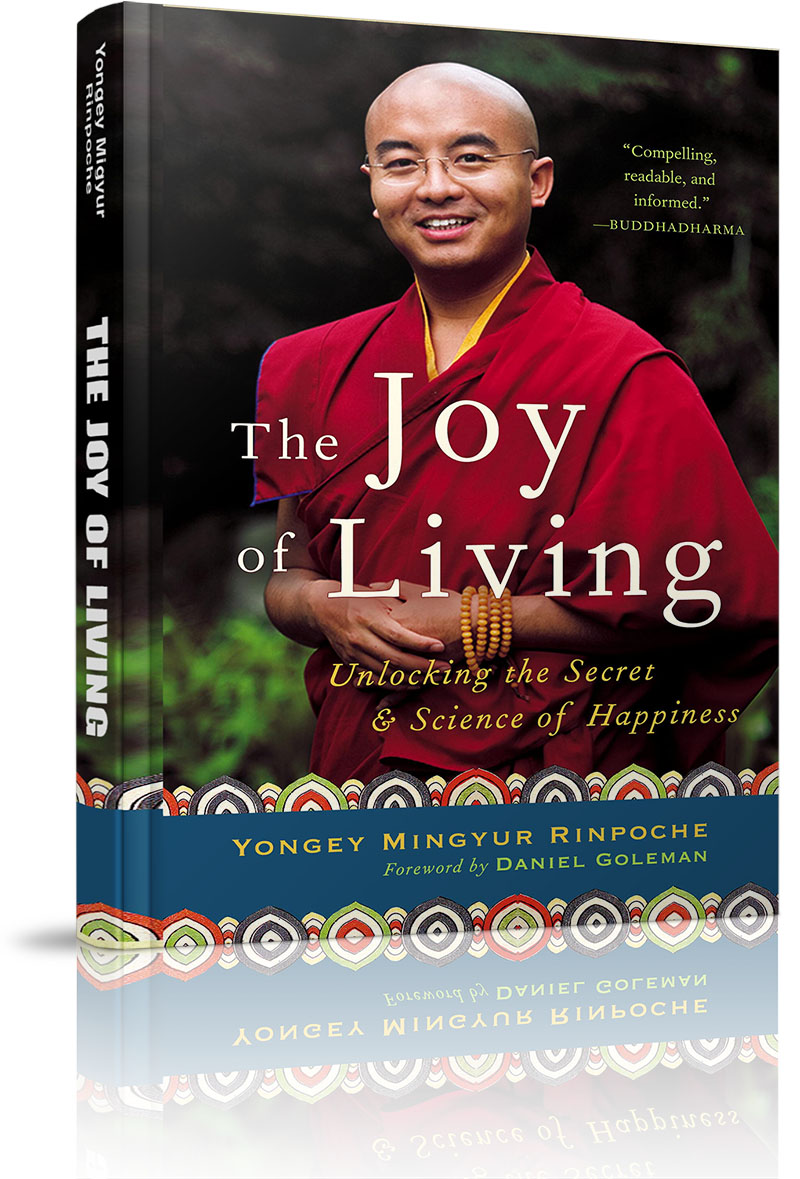

Trang chủ »» Danh mục »» SÁCH ANH NGỮ HOẶC SONG NGỮ ANH-VIỆT »» The Joy of Living »» 13. Compassion: Opening the heart of the mind »»

The Joy of Living

»» 13. Compassion: Opening the heart of the mind

Xem Mục lục

Xem Mục lục  Vietnamese || Đối chiếu song ngữ

Vietnamese || Đối chiếu song ngữ

- none

- Introduction

- Part One: The Ground - 1. The Journey Begins

- 2. The inner symphony

- 3. Beyond the mind, beyond the brain

- Emptiness: The reality beyond reality

- The relativity of perception

- 6. The Gift of Clarity

- 7. Compassion: Survival of the kindest

- 8. Why are we unhappy?

- Part Two: The Path - 9. Finding Your Balance

- 10. Simply resting: The first step

- 11. Next steps: Resting on objects

- 12. Working with thoughts and feelings

- »» 13. Compassion: Opening the heart of the mind

- 14. The how, when, and where of practice

- Part Three: The fruit - 15. Problems and Possibility

- 16. An inside job

- 17. The biology of happiness

- 18. Moving on

- none

- SANTIDEVA, The Bodhicaryavatara, translated by Kate Crosby and Andrew Skilton

Because we all live in a human society on a single planet, we have to learn to work together. In a world bereft of compassion, the only way we can work together is through the enforcement of outside agencies: police, armies, and the laws and weapons to back them up. But if we could learn to develop loving-kindness and compassion toward one another - a spontaneous understanding that whatever we do to benefit ourselves must benefit others and vice versa - we wouldn’t need laws or armies, police, guns, or bombs. In other words, the best form of security we can offer ourselves is to develop an open heart.

I’ve heard some people say that if everyone was kind and compassionate, the world would be a boring place. People would be no more than sheep, idling around with nothing to do. Nothing could be further from the truth. A compassionate mind is a diligent mind. There’s no end of problems in this world: Thousands of children die every day from starvation; people are slaughtered in wars that never even get reported in the newspapers; poisonous gases are building up in the atmosphere, threatening our very existence. But we don’t even have to look so far and wide to find suffering. We can see it all around us: in coworkers going through the pain of divorce; in relatives coping with physical or mental illness; in friends who’ve lost their jobs; and in hundreds of animals put to death every day because they’re unwanted, lost, or abandoned.

If you really want to see how active a compassionate mind can be, here’s a very simple exercise that probably won’t take more than five minutes of your time. Sit down with a pen and paper and make a list of ten problems that you’d like to see solved. It doesn’t matter whether they’re global problems or issues close to home. You don’t have to come up with solutions. Just write the list.

The simple act of writing this list will change your attitude significantly. It will awaken the natural compassion of your own true mind.

THE MEANING OF LOVING-KINDNESS AND COMPASSION

If we were to make a list of people we don’t like . . . we would find a lot about those aspects of ourselves that we can’t face.

- PEMA CHODRON, Start Where You Are

Recently, a student of mine told me that he thought “loving-kindness” and “compassion” were cold terms. They sounded too distant and academic, too much like an intellectual exercise in feeling sorry for other people. “Why,” he asked, “can’t we use a simpler, more direct word, like ‘love’?”

There are a couple of good reasons why Buddhists use the terms “loving-kindness” and “compassion” instead of a simpler one like “love.” Love, as a word, is so closely connected with the mental, emotional, and physical responses associated with desire that there’s some danger in associating this aspect of opening the mind with reinforcing the essentially dualistic delusion of self and other: “I love you,” or “I love that.” There’s a sense of dependence on the beloved object, and an emphasis on one’s personal benefit in loving and being loved. Of course, there are examples of love, such as the connection between a parent and a child, that transcend personal benefit to include the desire to benefit another. Most parents would probably agree that the love they experience toward their children involves more sacrifice than personal reward.

By and large, though, the terms “loving-kindness” and “compassion” serve as linguistic “stop signs.” They make us pause and think about our relationship to others. From a Buddhist perspective, loving-kindness is the aspiration that all other sentient beings - even those we dislike - experience the same sense of joy and freedom that we ourselves aspire to feel: a recognition that we all experience the same kinds of wants and needs; the desire to go about our lives peacefully and without fear of pain or harm. Even an ant or a cockroach experiences the same kinds of needs and fears that humans do. As sentient beings, we’re all alike; we’re all kindred. Loving-kindness implies a sort of challenge to develop this awareness of kindness or commonality on an emotional, even physical, level, rather than allowing it to remain an intellectual concept.

Compassion takes this capacity to look at another sentient being as equal to oneself even further. Its basic meaning is “feeling with,” a recognition that what you feel, I feel. Anything that hurts you hurts me. Anything that helps you helps me. Compassion, in Buddhist terms, is a complete identification with others and an active readiness to help them in any way.

Just look at it practically. If you lie to someone, for example, who have you really hurt? Yourself. You have to bear the burden of remembering the lie you told, covering your tracks, and maybe spinning a whole web of new lies to keep the original lie from being discovered. Or suppose you steal something, even something as small as a pen, from your office or some other place. Just think about the number of large and small actions you have to take to hide what you did. And despite all the energy you put into concealing what you did, you’ll almost inevitably be caught. There’s no way you can hide every single detail. So, in the end, all you’ve really done is wasted a lot of time and effort that you might have spent doing something more constructive.

Compassion is essentially the recognition that everyone and everything is a reflection of everyone and everything else. An ancient text called the Avatamsaka Sutra describes the universe as an infinite net brought into existence through the will of the Hindu god Indra. At every connection in this infinite net hangs a magnificently polished and infinitely faceted jewel, which reflects in each of its facets all the facets of every other jewel in the net. Since the net itself, the number of jewels, and the facets of every jewel are infinite, the number of reflections is infinite as well. When any jewel in this infinite net is altered in any way, all of the other jewels in the net change, too.

The story of Indra’s net is a poetic explanation for the sometimes mysterious connections that we observe between seemingly unrelated events. I’ve heard from a number of students recently that a lot of modern scientists have been grappling for a long time with the question of connections - or entanglements, as they are known to physicists - between particles that aren’t readily obvious to the human mind or to a microscope. Apparently, experiments involving subatomic particles conducted over the past few decades suggest that anything that was connected at one time retains that connection forever.

Like the jewels of Indra’s net, anything that affects one of these tiny particles automatically affects another, regardless of how far they’re separated by time or space. And since one of the current theories of modern physics holds that all matter was connected as a single point at the start of the big bang that created our universe, it’s theoretically possible - though as yet unproven - that whatever affects one particle in our universe also affects every other one.

The profound interrelatedness suggested by the story of Indra’s net, though currently only an analogy to contemporary scientific theory, may one day turn out to be scientific fact. And that possibility, in turn, transforms the whole idea of cultivating compassion from a nice idea into a matter of life-shaking proportions. Just by changing your perspective, you can not only alter your own experience, you can also change the world.

TAKING IT SLOWLY

Be free from any grasping for experience.

- THE NINTH GYALWANG KARMAPA,

Mahamudra: The Ocean of Definitive Meaning, translated by Elizabeth M. Callahan

Training in loving-kindness and compassion has to be undertaken gradually. It’s too easy, otherwise, to take on too much, too soon - a tendency exemplified by a cautionary tale I was told when I began this phase of my training. The story concerns Milarepa, widely regarded as one of Tibet’s greatest enlightened masters, who taught mainly through songs and poems he composed on the spot. During his lifetime, Milarepa traveled a great deal, and one day he arrived in a village and sat down to sing. One of the villagers heard his song and became completely entranced by the idea of giving up everything he was attached to and living as a hermit, in order to become enlightened as fast as possible and to help as many people in the world as he could during the years remaining to him.

When he told Milarepa what he meant to do, Milarepa gently advised him that it might be a better idea to stay at home for a while and start practicing compassion in a more gradual way. But the man insisted that he wanted to abandon everything right away, and, ignoring Milarepa’s advice, he rushed home and feverishly began giving away everything he owned, including his house. After tying a few necessary items in a handkerchief, he left for the mountains, found a cave, and sat down to meditate, without ever having practiced before and without ever having taken the time to learn how. Three days later, though, the poor man was hungry, exhausted, and freezing. After five days of starvation and discomfort, he wanted to go home, but was too embarrassed to do so. I made such a show about leaving everything and going to meditate, he thought, what will people think if I come back after only five days?

By the end of the seventh day, though, he couldn’t take the cold and hunger any longer and returned to his village. Sheepishly, he went around to all his neighbors asking if they would mind giving back his things. They returned everything he’d given away, and after he’d resettled himself, the man went back to Milarepa and, thoroughly humbled, asked for preliminary instructions in meditation. Following the gradual path Milarepa taught him, he eventually became a meditator of great wisdom and compassion and was able to benefit many others.

The moral of the story, of course, is to resist the temptation to rush into practice expecting immediate results. Since our dualistic perspective of “self and “other” didn’t develop overnight, we can’t expect to overcome it all at once. If we rush onto the path of compassion, at best we’ll end up like the villager who rashly gave up everything he owned. At worst we’ll end up regretting a charitable act, creating for ourselves a mental obstacle that may take years to overcome.

This point was repeatedly impressed on me by my father and my other teachers. If you take a gradual path, your life might not change tomorrow, next week, or even a month from now. But as you look back over the course of a year or many years, you will see a difference. You’ll find yourself surrounded by loving and supportive companions. When you come into conflict with other people, their words and actions won’t seem as threatening as they once did. Whatever pain or suffering you might sometimes feel will assume much more manageable, life-sized proportions, maybe even shrinking in importance compared with what other people you know may be going through.

The gradual path I was taught regarding the development of compassion toward others consisted of three “levels,” each to be practiced for several months - similar to the way students learn basic math skills - before moving on to higher applications.

“Level One” involved learning how to develop a kind or compassionate attitude toward yourself and other beings close to you.

“Level Two” focused on developing immeasurable loving-kindness and compassion toward all beings.

“Level Three” involves cultivating bodhicitta.

There are actually two types, or levels, of bodhicitta: absolute and relative. Absolute bodhicitta is a spontaneous recognition that all sentient beings, regardless of how they act or appear, are already completely enlightened. It usually takes a good deal of practice to attain this level of spontaneous recognition. Relative bodhicitta involves the cultivation of the desire for all sentient beings to become completely free of suffering through recognizing their true nature, and taking the actions to accomplish that desire.

LEVEL ONE

When you think of a condemned prisoner . . . imagine it’s you.

- PATRUL RINPOCHE, The Words of My Perfect Teacher, translated by the Padmakara Translation Group

Meditation on loving-kindness and compassion shares many similarities with the shinay practices we’ve already talked about. The main difference is the choice of the object on which we rest our attention and the methods we use to rest our attention. One of the most important lessons I learned during my years of formal training was that whenever I blocked the compassion that is a natural quality of my mind, I inevitably found myself feeling small, vulnerable, and afraid.

It’s so easy to think that we’re the only ones who suffer, while other people are somehow immune to pain, as though they’d been born with some kind of special knowledge about being happy that, through some cosmic accident, we never received. Thinking in this way, we make our own problems seem much bigger than they really are.

I’ve been as guilty of this belief as anyone else, and, as a result, have allowed myself to become isolated, trapped in a dualistic mode of thinking, pitting my weak, vulnerable, and fearful self against everyone else in the world, whom I thought of as much more powerful, happy, and secure. The power I fooled myself into believing other people held over me became a terrible threat to my own well-being. At any given moment, I thought, someone could find a way to undermine whatever security or happiness I’d managed to achieve.

After working with people over the years, I’ve come to realize that I wasn’t the only person to feel this way. Some part of our ancient, reptilian brain immediately evaluates whether we’re facing a friend or an enemy. This perception gradually extends even to inanimate objects until everything - a computer, a blown fuse, the blinking light on an answering machine - seems somewhat menacing.

When I began to practice meditation on compassion, however, I found that my sense of isolation began to diminish, while at the same time my personal sense of empowerment began to grow. Where once I saw only problems, I started to see solutions. Where once I viewed my own happiness as more important than the happiness of others, I began to see the well-being of others as the foundation of my own peace of mind.

The way I was taught, the development of loving-kindness and compassion begins with learning how to appreciate oneself. This is a hard lesson, especially for people brought up in cultures in which it’s common to dwell on personal weaknesses rather than on personal strengths. This is not a particularly Western problem. Developing a compassionate attitude toward myself literally saved my life during my first year in retreat. I could never have left my room if I hadn’t come to terms with my real nature, looking deep within my own mind and seeing the real power there, instead of the vulnerability I’d always thought was there.

One of the things that helped me as I sat alone in my room was remembering that the Sanskrit word for ‘‘human being” is purusha, which basically means “something that possesses power.” Being human means having power; specifically, the power to accomplish whatever we want. And what we want goes back to the basic biological urge to be happy and to avoid pain.

So, in the beginning, developing loving-kindness and compassion means using yourself as the object of your meditative focus. The easiest method is a kind of variation on the ‘‘scanning practice” described earlier. If you’re practicing formally, assume the seven-point posture to the best of your ability. Otherwise, just straighten your spine while keeping the rest of your body relaxed and balanced, and allow your mind simply to relax in a state of bare awareness.

After a few moments of resting your mind in objectless meditation, do a quick “scanning exercise,” gradually observing your physical body. As you scan your body, gently allow yourself to recognize how wonderful it is just to have a body, as well as a mind that’s capable of scanning it. Allow yourself to recognize how magnificent these very basic facts of your existence really are, how fortunate you are simply to have the great gifts of a body and a mind! Rest in that recognition for a moment, and then gently introduce the thought “How nice it would be if I were always able to enjoy this sense of basic goodness. How nice it would be if I could always enjoy this sense of well-being and all the causes that lead to feeling happy, peaceful, and good.”

Then just allow your mind to rest, open and relaxed. Don’t try to keep up this practice for more than three minutes if you’re practicing formally, or for more than a few seconds during informal meditation sessions. It’s very important to practice in short sessions and then allow your mind to rest. Short practice sessions followed by periods of rest allow this new awareness to stabilize - or, in Western scientific terms, give your brain a chance to establish new patterns without being overwhelmed by old neuronal gossip. Very simply, when you let go of practicing, you give yourself a chance to let the effects simply wash over you in a flood of positive feeling.

Once you’ve become somewhat familiar with your own desire for happiness, extending that awareness to other sentient beings around you - people, animals, and even insects - becomes much easier.

The practice of loving-kindness and compassion toward others essentially involves cultivating the recognition that all living creatures want to feel whole, safe, and happy. All you have to do is remember that whatever’s going on inside someone else’s mind is the same thing that’s going on in yours. When you remember this, you realize that there’s no reason to be frightened of anyone or anything. The only reason you’re ever scared is that you’ve failed to recognize that whomever or whatever you’re facing is just like you: a creature that only wants to be happy and free from suffering.

The classic Buddhist texts teach that we should focus first on our mothers, who have shown the ultimate kindness toward us by carrying us in their bodies, bringing us into the world, and nurturing us throughout the early years of our lives, often at great sacrifice to themselves. I understand that many people in Western cultures don’t always enjoy tender and affectionate relationships with their parents - in which case using one’s mother or father as an object of meditation wouldn’t be very practical. It’s perfectly acceptable in such cases to focus on another object, such as an especially kind relative, a teacher, a close friend, or a child. Some people choose to focus on their pets. The object of your meditation doesn’t really matter; the important thing is to rest your attention lightly on someone or something toward which you feel a deep sense of tenderness or warmth.

When you take up loving-kindness and compassion as a formal practice, begin by assuming either the seven-point posture or, at the very least (if you’re sitting on a bus or a train, for example), straightening your spine while allowing the rest of your body to rest naturally. As with any meditation practice, once you’ve got your body positioned, the next step is simply to allow your mind to rest naturally for a few moments and let go of whatever you might have been thinking about. Just let your mind breathe a huge sigh of relief.

After resting your mind for a few moments in objectless meditation, lightly bring your awareness to someone toward whom it’s easiest for you to feel tenderness, affection, or concern. Don’t be surprised if the image of someone or something you didn’t deliberately choose appears more strongly than the object you may have decided to work with. This happens, often quite spontaneously. One of my students began formal practice intending to focus on his grandmother, who had been very kind to him when he was young; but the image that kept appearing to him was a rabbit he’d owned as a child. This is just an example of the mind’s natural wisdom asserting itself. He actually had a lot of warm memories associated with the rabbit, and when he finally surrendered to them, his practice became quite easy.

Sometimes you may find that your mind spontaneously produces memories of a particularly nice experience you shared with someone, rather than a more abstract image of the person you’ve chosen as an object of meditation. That’s fine, too. The important point in cultivating loving-kindness and compassion is to allow yourself to experience genuine feelings of warmth, tenderness, or affection.

As you proceed, allow the sense of warmth or affection to settle in your mind, like a seed planted in soil, alternating for a few minutes between this experience and simply allowing your mind to rest in objectless meditation. As you alternate between these two states, allow yourself to wish that the object of your meditation might experience the same sense of openness and warmth you feel toward him or her.

After practicing in this way for a while, you’re ready to move a little bit deeper. Begin as before, assuming an appropriate posture and allowing your mind to rest in objectless meditation for a few moments, and then bring to mind the object of your loving-kindness and compassion. Once you’ve settled on the object of your meditation, there are a couple of ways to proceed. The first is to imagine the object you’ve chosen in a very sad or painful state. Of course, if the object you’ve chosen is already in deep pain or sorrow, you can simply bring to mind his or her present condition. Either way, the image you call to mind naturally produces a profound sense of love and connectedness, and a deep desire to help. Thinking that someone or something you care for is in pain can break your heart. But a broken heart is an open heart. Every heartbreak is an opportunity for love and compassion to flow through you.

Another approach is to rest your attention lightly on the subject you’ve chosen while asking yourself, “How much do I want to be happy? How much do I want to avoid pain or suffering?” Let your thoughts on these points be as specific as possible. For example, if you’re stuck somewhere stiflingly hot, would you rather move to a cooler and more open place? If you feel some sort of physical pain, would you like the pain to be lifted? As you think about your own answers, gradually turn your attention to the subject you’ve chosen and imagine how he or she would feel in the same situation. Practicing in this way not only opens your heart to other beings, but also dissolves your own identification with whatever pain or discomfort you may be experiencing at the moment.

Cultivating loving-kindness and compassion toward those you know and care about already isn’t so hard because even when you want to strangle them for being stupid or obstinate, the bottom line is that you still love them. It’s a little bit harder to extend the same sense ol warmth and relatedness toward those you don’t know - and even harder to extend that awareness to those you actively dislike.

I heard a story a while back about a man and a woman living in China, maybe forty or fifty years ago. They’d just gotten married, and when the bride moved into her husband’s home, she immediately started fighting with her mother-in-law over a number of petty issues about how the household should be run. Gradually their disagreements escalated until the new bride and her mother-in-law couldn’t even stand to look at each other. The bride saw her mother-in-law as an interfering old witch, while the mother-in-law thought of her son’s young bride as an arrogant child, with no respect for her elders.

There was no real reason for their anger to escalate as it had. But eventually the bride became so angry at her mother-in-law that she decided she had to do something to get her out of the way. So she went to a doctor and asked for poison that she could put into her mother-in-law’s food.

After hearing the young bride’s complaints, the doctor agreed to sell her some poison.

“But,” he warned, “if I were to give you something strong that worked immediately, everyone would point their fingers at you and say, ‘You poisoned your mother-in-law,’ and they’d also find out that you bought the poison from me, and that wouldn’t be good for either of us. So I’m going to give you a gentle poison that will take effect very gradually, so she won’t die right away.”

He also instructed her that while she administered the poison, she should treat her mother-in-law very, very nicely.

“Serve every meal with a smile,” he advised. “Tell her you hope she enjoys her food and ask her if there’s anything else you might bring her. Be very humble and sweet, so no one will suspect you.’’

The bride agreed, and carried the poison back home with her. That very evening she started adding the poison to her mother-in-law’s food, and very politely offered the meal to her. After a few days of being treated so respectfully, the mother-in-law began to change her opinion about her son’s wife. Maybe she’s not so arrogant after all, the old woman thought. Maybe I was wrong about her.

And little by little she started treating her daughter-in-law more agreeably, complimenting her on her cooking and on the way she was managing the household, and even exchanging little tidbits of gossip and funny stories.

As the old woman’s attitude and behavior changed, of course, so did the girl’s. After a few days she started thinking, Maybe my mother-in-law isn’t as bad as I thought. In fact, she seems pretty nice.

This continued for a month or so, until the two women actually started to become very good friends. They started getting along so well that at a certain point the girl stopped poisoning her mother-in-law’s food. Then she started to worry because she realized she’d already put so much poison in every meal that her mother-in-law would very likely die.

So she went back to the doctor and told him, “I made a mistake. My mother-in-law is actually a really nice person. I shouldn’t have poisoned her. Please help me out and give me an antidote to the poison I gave her.”

The doctor sat very quietly for a moment after listening to the girl. “I’m very sorry,” he told her. “I can’t help you now. There is no antidote.”

On hearing that, the girl became terribly upset and started to cry, swearing that she was going to kill herself.

“Why would you want to kill yourself?” the doctor asked.

The girl answered, “Because I’ve poisoned such a nice person and now she’s going to die. So I should take my own life to punish myself for the terrible thing I did.”

Again the doctor sat quietly for a moment, and then he started to chuckle.

“How can you laugh about this?” the girl demanded.

Because there’s really no need for you to worry,” he replied. “There’s no antidote to the poison because I never gave you any poison to begin with. All I gave you was a harmless herb.”

I like this story because it’s such a simple example of how easily a natural transformation of experience can occur. At first the new bride and her mother-in-law hated each other. Each thought that the other was simply awful. Once they started to treat each other differently, though, they began to see each other in a different light. Each saw the other as a basically good person, and eventually they became close friends. As people, they hadn’t really changed at all. The only thing that changed was their perspective.

The nice thing about such stories is that they compel us to see that our initial impressions about others may be wrong or misguided. There’s no reason to feel guilty about such mistakes; they’re merely the result of ignorance. And, fortunately, the Buddha provided a meditation practice that provides not only the means for amending such mistakes, but for preventing them in the future. This practice is known in English as “exchanging yourself for others,” which in simple terms means imagining yourself in the position of someone or something you don’t like very much.

Although the practice of exchanging yourself for others can be performed anytime, anywhere, it’s helpful to get the basics down through formal practice. Formal practice is a bit like charging the battery in a cell phone. Once the battery is fully charged, you can use the cell phone for a long time, in a variety of places and under a variety of circumstances. Eventually, though, the battery runs down, and you need to charge it again. The main difference between charging a battery and developing loving-kindness and compassion is that ultimately, through formal practice, the habit of responding compassionately to other beings creates a series of neuronal connections that constantly perpetuates itself and doesn’t lose its “charge.”

The first step in formal practice is, as usual, to assume a correct posture and allow your mind to rest for a few moments. Then bring to mind someone or something that you don’t like. Don’t judge what you feel. Give yourself complete permission to feel it. Simply letting go of judgments and justifications will let you experience a certain degree of openness and clarity.

The next step is to admit to yourself that whatever you’re feeling - anger, resentment, jealousy, or desire - is in itself the source of whatever pain or discomfort you’re experiencing. The object of your feeling isn’t the source of your pain, but rather your own mentally generated response to whomever or whatever you’re focusing on.

For example, you might bring your attention to someone who’s said something to you that sounded cruel, critical, or contemptuous - or even to someone who has told you an outright lie. Then, allow yourself to recognize that all that has occurred is that someone has emitted sounds and you have heard them. If you’ve spent even a little bit of time practicing calm-abiding meditation on sound, this aspect of “ex-changing self for others” will probably feel familiar.

At this point, three options are available to you.

The first, and most likely, option is to allow yourself to be consumed by anger, guilt, or resentment.

The second (which is very unlikely) is to think, I should have spent more time meditating on sound.

The third option is to imagine yourself as the person who said or did whatever you felt as painful. Ask yourself whether what that person said or did was really motivated by a desire to hurt you, or whether he or she was trying to alleviate his or her own pain or fear.

In many cases, you know the answer already. You may have overheard some talk about the other person’s health or relationship, or some threat to his or her professional standing. But even if you don’t know the specifics of a person’s situation, you’ll know from your own practice of developing compassion for yourself and of extending it toward others that there is only one possible motive behind someone’s behavior: the desire to feel safe or happy. And if people say or do something hurtful, it’s because they don’t feel safe or happy. In other words, they’re scared.

And you know what it’s like to be scared.

Recognizing this about someone else is the essence of exchanging self for others.

Another method of exchanging yourself for others is to choose a “neutral” focus - a person or an animal you may not know directly, but whose suffering you’re somewhat aware of. Your focus could be a child in a foreign country, dying of thirst or hunger, or an animal caught in a steel trap, desperately chewing off its leg to escape.

These “neutral” beings experience all kinds of suffering over which they have no control and from which they cannot protect or free themselves. Yet the pain they feel and their desperate desire to free themselves from it are easily understandable, because you share the same basic longing. So, even though you don’t know them, you recognize their state of mind, and experience their pain and fear as your own. I’m willing to bet that extending compassion in this way - toward those you don’t like or those you don’t know - won’t turn you into a boring, lazy old sheep.

LEVEL TWO

May all beings have happiness and the causes of happiness.

- The Four Immeasurables

There’s a particular meditation practice that can help generate immeasurable loving-kindness and compassion. In Tibetan, this practice is called tonglen, which may be translated into English as “sending and taking.”

Tonglen is actually quite an easy practice, requiring only a simple coordination of imagination and breathing. The first step is simply to recognize that as much as you want to achieve happiness and avoid suffering, other beings also feel the same way. There is no need to visualize specific beings, although you may start out with a specific visualization if you find it helpful. Eventually, however, the practice of taking and sending extends beyond those you can imagine to include all sentient beings - including animals, insects, and inhabitants of dimensions you don’t possess the knowledge or capacity to see.

The point, as I was taught, is simply to remember that the universe is filled with an infinite number of beings, and to think, Just as I want happiness, all beings want happiness. Just as I wish to avoid suffering, all beings wish to avoid suffering. I am just one person, while the number of other beings is infinite. The well-being of this infinite number is more important than that of one. And as you allow these thoughts to roll around in your mind, you’ll actually begin to find yourself actively engaged in wishing for others’ freedom from suffering.

Begin by assuming a correct posture and allowing your mind to simply rest for a few moments. Then use your breath to send all your happiness to all sentient beings and absorb their suffering. As you exhale, imagine all the happiness and benefits you’ve acquired during your life pouring out of yourself in the form of pure light that spreads to all beings and dissolves into them, fulfilling all their needs and eliminating their suffering. As soon as you start to breathe out, imagine the light immediately touching all beings, and that by the time you finish exhaling, the light has already dissolved into them. As you inhale, imagine the pain and suffering of all sentient beings as a dark, smoky light being absorbed through your nostrils and dissolving into your heart.

As you continue this practice, imagine that all beings are freed from suffering, and filled with bliss and happiness. After practicing in this way for a few moments, simply allow your mind to rest. Then take up the practice again, alternating between periods of tonglen and resting your mind.

If it helps your visualization, you can sit with your body very straight and rest your hands in loosely closed fists on the tops of your thighs. As you breathe out, open your fingers and slide your hands down your thighs toward your knees while you imagine the light going out toward all beings. As you inhale, slide your hands back up, forming loosely closed fists as through drawing the dark light of others’ suffering and dissolving it into yourself.

The universe is filled with so many different kinds of creatures, it’s impossible even to imagine them all, much less offer direct and immediate help to each and every one. But through the practice of tonglen, you open your mind to infinite creatures and wish for their well-being. The result is that eventually your mind becomes clearer, calmer, more focused and aware, and you develop the capacity to help others in infinite ways, both directly and indirectly.

An old Tibetan folktale illustrates the benefits of developing this sort of all-encompassing compassion. A nomad who spent his days walking across the mountains was constantly pained by the rough and thorny ground because he didn’t have any shoes. Over the course of his travels, he began to collect the skins of dead animals and spread them along the mountain paths, covering the stones and thorns. The problem was that even with great effort, he could only cover several hundred square yards. At last it came to him that if he simply used a few small hides to make himself a pair of shoes, he could walk for thousands of miles without any pain. Simply by covering his feet with leather, he covered the entire earth with leather.

In the same way, if you try to deal with each conflict, each emotion, and each negative thought as it occurs, you’re like the nomad trying to cover the world with leather. If, instead, you work at developing a loving and peaceful mind, you can apply the same solution to every problem in your life.

LEVEL THREE

A person who has . . . awakened the force of genuine compassion will be quite capable of working physically, verbally, and mentally for the welfare of others.

- JAMGON KONGTRUL, The Torch of Certainty, translated by Judith Hanson

The practice of bodhicitta - the mind of awakening - may seem almost magical, in the sense that when you choose to deal with other people as if they were already fully enlightened, they tend to respond in a more positive, confident, and peaceful manner than they otherwise might. But really there is nothing magical about the process. You’re simply looking at and acting toward people on the level of their full potential, and they respond to the best of their ability in the same way.

As mentioned earlier, there are two aspects of bodhicitta, absolute and relative. Absolute bodhicitta is the direct insight into the nature of mind. Within absolute bodhicitta, or the absolutely awakened mind, there is no distinction between subject and object, self and other; all sentient beings are spontaneously recognized as perfect manifestations of Buddha nature. Very few people are capable of experiencing absolute bodhicitta right away, however. I certainly wasn’t. Like most people, I needed to train along the more gradual path of relative bodhicitta.

There are several reasons why this path is referred to as “relative.” First, it is related to absolute bodhicitta in the sense that it shares the same goal: the direct experience of Buddha nature, or awakened mind.

To use an analogy, absolute bodhicitta is like the top floor of a building, while relative bodhicitta may be compared to the lower floors. All the floors are part of the same building, but each of the lower floors stands in a relative relationship to the top floor. If we want to reach the top floor, we have to pass through all of the lower floors.

Second, when we’ve achieved the state of absolute bodhicitta, there is no distinction between sentient beings; every living creature is understood as a perfect manifestation of Buddha nature. In the practice of relative bodhicitta, however, we’re still working within the framework of a relationship between subject and object or self and other.

Finally, according to many great teachers, such as Jamgon Kongtrul in his book The Torch of Certainty, development of absolute bodhicitta depends on developing relative bodhicitta.

Developing relative bodhicitta always involves two aspects: aspiration and application.

Aspiration bodhicitta involves cultivating the heartfelt desire to raise all sentient beings to the level at which they recognize their Buddha nature. We begin by thinking, I wish to attain complete awakening in order to help all sentient beings attain the same state. Aspiration bodhicitta focuses on the fruit, or the result, of practice. In this sense, aspiration bodhicitta is like focusing on the goal of carrying everyone to a certain destination - for example, London, Paris, or Washington, D.C. In the case of aspiration bodhicitta, of course, the “destination” is the total awakening of the mind, or absolute bodhicitta.

Application bodhicitta - often compared in classic texts to actually taking the steps to arrive at an intended destination - focuses on the path of attaining the goal of aspiration bodhicitta: the liberation of all sentient beings from all forms and causes of suffering through recognition of their Buddha nature.

As mentioned, while practicing relative bodhicitta, we’re still caught up in regarding other sentient beings from a slightly dualistic perspective, as if their existence were relative to our own. But when we generate the motivation to lift not only ourselves but all sentient beings to the level of complete recognition of Buddha nature, an odd thing happens: The dualistic perspective of “self and “other” begins very gradually to dissolve, and we grow in wisdom and power to help others as well as ourselves.

As an approach to life, cultivating relative bodhicitta is certainly an improvement on the way we ordinarily deal with others, though it does take a certain amount of work. It’s so easy to condemn other people who don’t agree with our own point of view, isn’t it? Most of us do so as easily and unthinkingly as smashing a mosquito, a cockroach, or a fly. The essence of developing relative bodhicitta is to recognize that the desire to squash a bug and the urge to condemn a person who disagrees with us are fundamentally the same. It’s a fight-or-flight response deeply embedded in the reptilian layer of our brains - or, to put it more bluntly, our crocodile nature.

So the first step in developing relative bodhicitta is to decide, “Would I rather be a crocodile or a human being?”

Certainly there are advantages to being a crocodile. Crocodiles are very good at outsmarting their enemies and simply surviving. But they cannot love or experience being loved. They don’t have friends. They can never experience the joys of raising children. They have very little appreciation for art or music. They can’t laugh. And many of them end up as shoes.

If you’ve gotten this far in reading this book, chances are you’re not a crocodile. But you’ve probably met a few people who act like crocodiles. The first step in developing relative bodhicitta is to let go of your distaste for “crocodile-like” people and cultivate some sense of compassion toward them, because they don’t recognize how much of the richness and beauty of life they’re missing.

Once you can do that, extending relative bodhicitta toward all sentient beings - including real crocodiles and whatever other living creatures might annoy, frighten, or disgust you - becomes a lot easier. If you just take a moment to think about how much these creatures are missing out on, your heart will almost automatically open up to them.

Actually, aspiration bodhicitta and application bodhicitta are like two sides of the same coin. One can’t exist without the other. Aspiration bodhicitta is the cultivation of an unrestricted readiness to help all living beings achieve a state of complete happiness and freedom from pain and suffering. Whether you’re actually able to free them doesn’t matter. The important thing is your intention. Application bodhicitta involves the activities required to carry out your intention. Practicing one aspect strengthens your ability to cultivate the other.

There are many ways to practice application bodhicitta: for example, trying your best to refrain from stealing, lying, gossiping, and speaking or acting in ways that intentionally cause pain; acting generously toward others; patching up quarrels; speaking gently and calmly rather than “flying off the handle”; and rejoicing in the good things that happen to other people rather than allowing yourself to become overwhelmed by jealousy or envy. Conduct of this sort is a means of extending the experience of meditation into every aspect of daily life.

There is no greater inspiration, no greater courage, than the intention to lead all beings to the perfect freedom and complete well-being of recognizing their true nature. Whether you accomplish this intention isn’t important. The intention alone has such power that as you work with it, your mind will become stronger; your mental afflictions will diminish; you’ll become more skillful in helping other beings; and in so doing, you’ll create the causes and conditions for your own well-being.

MUA THỈNH KINH SÁCH PHẬT HỌC

DO NXB LIÊN PHẬT HỘI PHÁT HÀNH

Mua sách qua Amazon sẽ được gửi đến tận nhà - trên toàn nước Mỹ, Canada, Âu châu và Úc châu.

Quý vị đang truy cập từ IP 216.73.216.44, 147.243.246.8 và chưa ghi danh hoặc đăng nhập trên máy tính này. Nếu là thành viên, quý vị chỉ cần đăng nhập một lần duy nhất trên thiết bị truy cập, bằng email và mật khẩu đã chọn.

Chúng tôi khuyến khích việc ghi danh thành viên ,để thuận tiện trong việc chia sẻ thông tin, chia sẻ kinh nghiệm sống giữa các thành viên, đồng thời quý vị cũng sẽ nhận được sự hỗ trợ kỹ thuật từ Ban Quản Trị trong quá trình sử dụng website này.

Việc ghi danh là hoàn toàn miễn phí và tự nguyện.

Ghi danh hoặc đăng nhập

... ...

Trang chủ

Trang chủ