Chúng ta không có khả năng giúp đỡ tất cả mọi người, nhưng mỗi người trong chúng ta đều có thể giúp đỡ một ai đó. (We can't help everyone, but everyone can help someone.)Ronald Reagan

Để có đôi mắt đẹp, hãy chọn nhìn những điều tốt đẹp ở người khác; để có đôi môi đẹp, hãy nói ra toàn những lời tử tế, và để vững vàng trong cuộc sống, hãy bước đi với ý thức rằng bạn không bao giờ cô độc. (For beautiful eyes, look for the good in others; for beautiful lips, speak only words of kindness; and for poise, walk with the knowledge that you are never alone.)Audrey Hepburn

Thương yêu là phương thuốc diệu kỳ có thể giúp mỗi người chúng ta xoa dịu những nỗi đau của chính mình và mọi người quanh ta.Tủ sách Rộng Mở Tâm Hồn

Đừng chọn sống an nhàn khi bạn vẫn còn đủ sức vượt qua khó nhọc.Sưu tầm

Sự giúp đỡ tốt nhất bạn có thể mang đến cho người khác là nâng đỡ tinh thần của họ. (The best kind of help you can give another person is to uplift their spirit.)Rubyanne

Ý dẫn đầu các pháp, ý làm chủ, ý tạo; nếu với ý ô nhiễm, nói lên hay hành động, khổ não bước theo sau, như xe, chân vật kéo.Kinh Pháp Cú (Kệ số 1)

Như ngôi nhà khéo lợp, mưa không xâm nhập vào. Cũng vậy tâm khéo tu, tham dục không xâm nhập.Kinh Pháp cú (Kệ số 14)

Điều quan trọng không phải là bạn nhìn vào những gì, mà là bạn thấy được những gì. (It's not what you look at that matters, it's what you see.)Henry David Thoreau

Không làm các việc ác, thành tựu các hạnh lành, giữ tâm ý trong sạch, chính lời chư Phật dạy.Kinh Đại Bát Niết-bàn

Chúng ta nên hối tiếc về những sai lầm và học hỏi từ đó, nhưng đừng bao giờ mang theo chúng vào tương lai. (We should regret our mistakes and learn from them, but never carry them forward into the future with us. )Lucy Maud Montgomery

Sự hiểu biết là chưa đủ, chúng ta cần phải biết ứng dụng. Sự nhiệt tình là chưa đủ, chúng ta cần phải bắt tay vào việc. (Knowing is not enough; we must apply. Willing is not enough; we must do.)Johann Wolfgang von Goethe

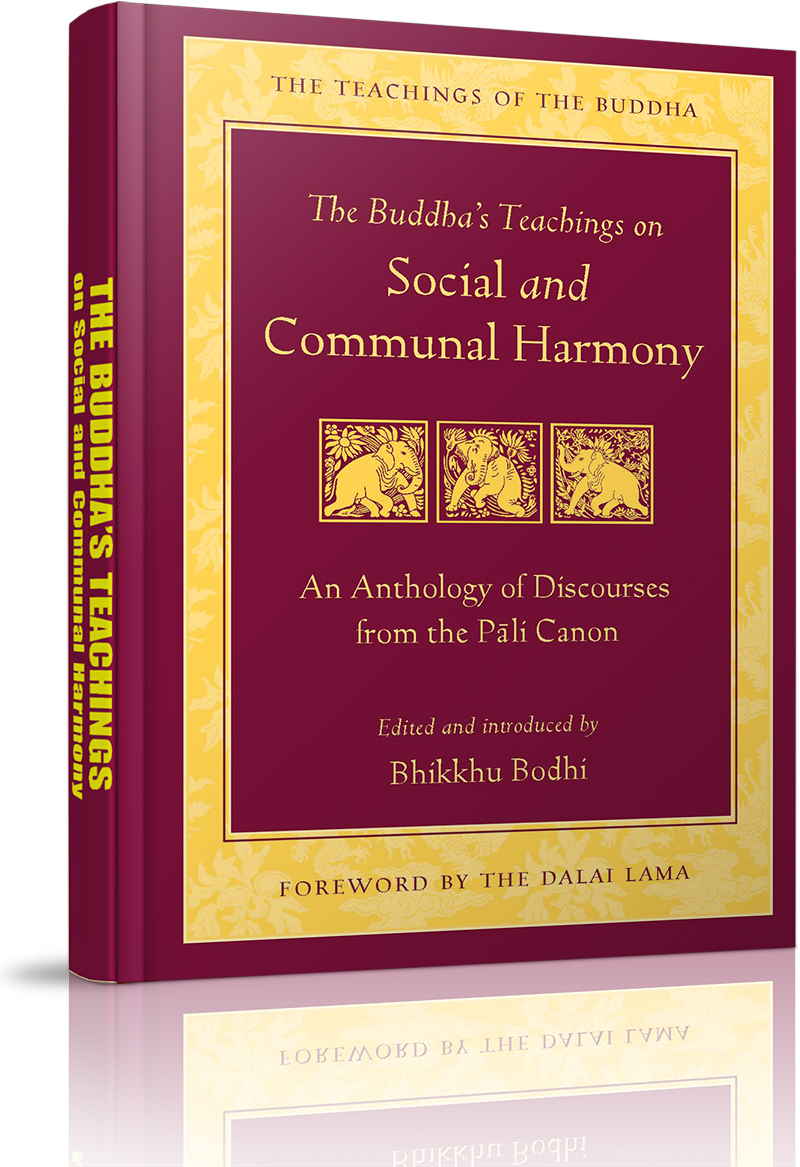

Trang chủ »» Danh mục »» TỦ SÁCH RỘNG MỞ TÂM HỒN »» The Buddha's Teachings on Social and Communal Harmony »» none »»

The Buddha's Teachings on Social and Communal Harmony

»» none

Xem Mục lục

Xem Mục lục

- About Bhikkhu Bodhi

- Foreword by His Holiness The Dalai Lama

- »» none

- General Introduction

- I. RIGHT UNDERSTANDING

- II. PERSONAL TRAINING

- III. DEALING WITH ANGER

- IV. PROPER SPEECH

- V. GOOD FRIENDSHIP

- VI. ONE’S OWN GOOD AND THE GOOD OF OTHERS

- VII. THE INTENTIONAL COMMUNITY

- VIII. DISPUTES

- IX. SETTLING DISPUTES

- X. ESTABLISHING AN EQUITABLE SOCIETY

- Epilogue BY HOZAN ALAN SENAUKE

Gotama Buddha came of age in a land of kingdoms, tribes, and varna, meaning social class or caste. It was a time and place both distinct from and similar to our own, in which a person’s life was strongly determined by social status, family occupation, cultural identity, and gender. Before the Buddha’s awakening, identity was definitive. If one was born into a warrior caste or that of a merchant or a farmer or an outcast, one lived that life completely and almost always married someone from the same class or caste. One’s children did the same. There was no sense of individual rights or personal destiny, no way to manifest one’s human abilities apart from a societal role assigned at birth. So the Buddha’s teaching can be seen as a radical assertion of individual potentiality. Only by one’s effort was enlightenment possible, beyond the constraints of caste, position at birth, or conventional reality. In verse 396 of the Dhammapada, the Buddha says:

I do not call one a brahmin only because of birth, because he is born of a (brahmin) mother. If he has attachments, he is to be called only “self-important.” One who is without attachments, without clinging — him do I call a brahmin.

At the same time, the Buddha and his disciples lived in the midst of society. They didn’t set up their monasteries on isolated mountaintops but on the outskirts of large cities such as Sāvatthī, Rājagaha, Vesālī, and Kosambī. They depended on laywomen and men, upāsikā and upāsaka, for the requisites of life. Even today monks and nuns in the Theravāda tradition of Burma (or Myanmar), Thailand, Sri Lanka, Cambodia, and Laos go on morning alms rounds for their food. Although they keep a strict monastic discipline, it is mistaken to imagine that Southeast Asian monasteries are cloistered and apart from their brothers and sisters in the secular world. Monasteries and secular communities are mutually dependent, in a tradition that is sweet and fully alive.

In the autumn of 2007 people around the world were inspired by Burma’s determined yet peaceful “Saffron Revolution” — led by a nonviolent protest of Burmese monks against the military government’s repression.

The protests were triggered by sudden and radical increases in fuel prices that drastically affected people’s ability to get to work or to afford fuel for cooking or even basic foods. The intimate connection between monks, nuns, and laypeople has historically meant that when one sector is suffering, the other responds. Burmese monks have a long history of speaking out against injustice. They have been bold in opposition to British colonialism, dictatorship, and two decades of a military junta.

In Burma Buddhist monks have been agents of change in a society that stands on the brink of real transformation. While this change is inevitable, the military junta had previously resisted it with grim determination. A confluence of circumstances created an opening: the election of a new civilian government (however one might question the electoral process), the release of political prisoners (including Nobel laureate Daw Aung San Suu Kyi after many years of house arrest), nonviolent movements around the world encouraged by 2011’s “Arab Spring,” and a new dialogue between Burma’s leaders and representatives from Europe, the United States, and other economic powers. There was a feeling of possibility and hope in the air.

This anthology underscores living within the Dhamma in a free and harmonious society, using the Buddha’s time-tested words. Returning from Burma in November of 2011, I had been thinking about the need there and elsewhere for this kind of collection from the Pāli suttas. In 2012 communal violence erupted in Burma’s Rakhine State and elsewhere in that country. A need to look deeply into the Buddha’s teachings on social harmony has become urgent. Not being a scholar or a translator, I contacted several learned friends. It turns out that several years back Bhikkhu Bodhi, one of our most respected and prolific interpreters of Early Buddhism, had assembled such a collection as an addendum to a training curriculum for social harmony in Sri Lanka, organized by the Institute for the Study of Human Rights at Columbia University.

Here is the Buddha’s advice about how to live harmoniously in societies that are not oppressing those of different religions or ethnic backgrounds, not savaging and exploiting themselves or others. While circumstances in Burma, Sri Lanka, Thailand, India, or the United States vary, the Buddha’s social teachings offer a kind of wisdom that transcends the particularities of time and place. His teachings provide a ground of liberation upon which each nation and people can build according to its own needs.

I am most grateful to Bhikkhu Bodhi for his wisdom and generosity. People of all faiths and beliefs in every land yearn for happiness and liberation. I honor those who move toward freedom, and hope that the Buddha’s words on social harmony may lead us fearlessly along our path.

Berkeley, CA

___________________

Acknowledgments

In 2011 Bhikkhu Khemaratana shared with me an outline of texts from the Pāli Canon that he had prepared on the theme of monastic harmony, a topic in which he has been particularly interested. The texts that I have chosen for several sections of this anthology were suggested by those selected by Ven. Khemaratana, though my treatment of the topic has been governed by the purpose of this anthology and thus differs from his outline. I am also grateful to Alan Senauke for writing a prologue and epilogue to this volume, drawing upon his own experience using the earlier version of this anthology in his work of fostering social harmony and reconciliation in India and Myanmar.

MUA THỈNH KINH SÁCH PHẬT HỌC

DO NXB LIÊN PHẬT HỘI PHÁT HÀNH

Mua sách qua Amazon sẽ được gửi đến tận nhà - trên toàn nước Mỹ, Canada, Âu châu và Úc châu.

Quý vị đang truy cập từ IP 216.73.216.34 và chưa ghi danh hoặc đăng nhập trên máy tính này. Nếu là thành viên, quý vị chỉ cần đăng nhập một lần duy nhất trên thiết bị truy cập, bằng email và mật khẩu đã chọn.

Chúng tôi khuyến khích việc ghi danh thành viên ,để thuận tiện trong việc chia sẻ thông tin, chia sẻ kinh nghiệm sống giữa các thành viên, đồng thời quý vị cũng sẽ nhận được sự hỗ trợ kỹ thuật từ Ban Quản Trị trong quá trình sử dụng website này.

Việc ghi danh là hoàn toàn miễn phí và tự nguyện.

Ghi danh hoặc đăng nhập

... ...

Trang chủ

Trang chủ