Ai sống quán bất tịnh, khéo hộ trì các căn, ăn uống có tiết độ, có lòng tin, tinh cần, ma không uy hiếp được, như núi đá, trước gió.Kinh Pháp Cú (Kệ số 8)

Thành công không phải là chìa khóa của hạnh phúc. Hạnh phúc là chìa khóa của thành công. Nếu bạn yêu thích công việc đang làm, bạn sẽ thành công. (Success is not the key to happiness. Happiness is the key to success. If you love what you are doing, you will be successful.)Albert Schweitzer

Kẻ không biết đủ, tuy giàu mà nghèo. Người biết đủ, tuy nghèo mà giàu. Kinh Lời dạy cuối cùng

Cuộc sống là một sự liên kết nhiệm mầu mà chúng ta không bao giờ có thể tìm được hạnh phúc thật sự khi chưa nhận ra mối liên kết ấy.Tủ sách Rộng Mở Tâm Hồn

Ai sống quán bất tịnh, khéo hộ trì các căn, ăn uống có tiết độ, có lòng tin, tinh cần, ma không uy hiếp được, như núi đá, trước gió.Kinh Pháp cú (Kệ số 8)

Sống trong đời cũng giống như việc đi xe đạp. Để giữ được thăng bằng bạn phải luôn đi tới. (Life is like riding a bicycle. To keep your balance you must keep moving. )Albert Einstein

Thành công là tìm được sự hài lòng trong việc cho đi nhiều hơn những gì bạn nhận được. (Success is finding satisfaction in giving a little more than you take.)Christopher Reeve

Yêu thương và từ bi là thiết yếu chứ không phải những điều xa xỉ. Không có những phẩm tính này thì nhân loại không thể nào tồn tại. (Love and compassion are necessities, not luxuries. Without them humanity cannot survive.)Đức Đạt-lai Lạt-ma XIV

Tôi tìm thấy hy vọng trong những ngày đen tối nhất và hướng về những gì tươi sáng nhất mà không phê phán hiện thực. (I find hope in the darkest of days, and focus in the brightest. I do not judge the universe.)Đức Đạt-lai Lạt-ma XIV

Phán đoán chính xác có được từ kinh nghiệm, nhưng kinh nghiệm thường có được từ phán đoán sai lầm. (Good judgment comes from experience, and often experience comes from bad judgment. )Rita Mae Brown

Nếu quyết tâm đạt đến thành công đủ mạnh, thất bại sẽ không bao giờ đánh gục được tôi. (Failure will never overtake me if my determination to succeed is strong enough.)Og Mandino

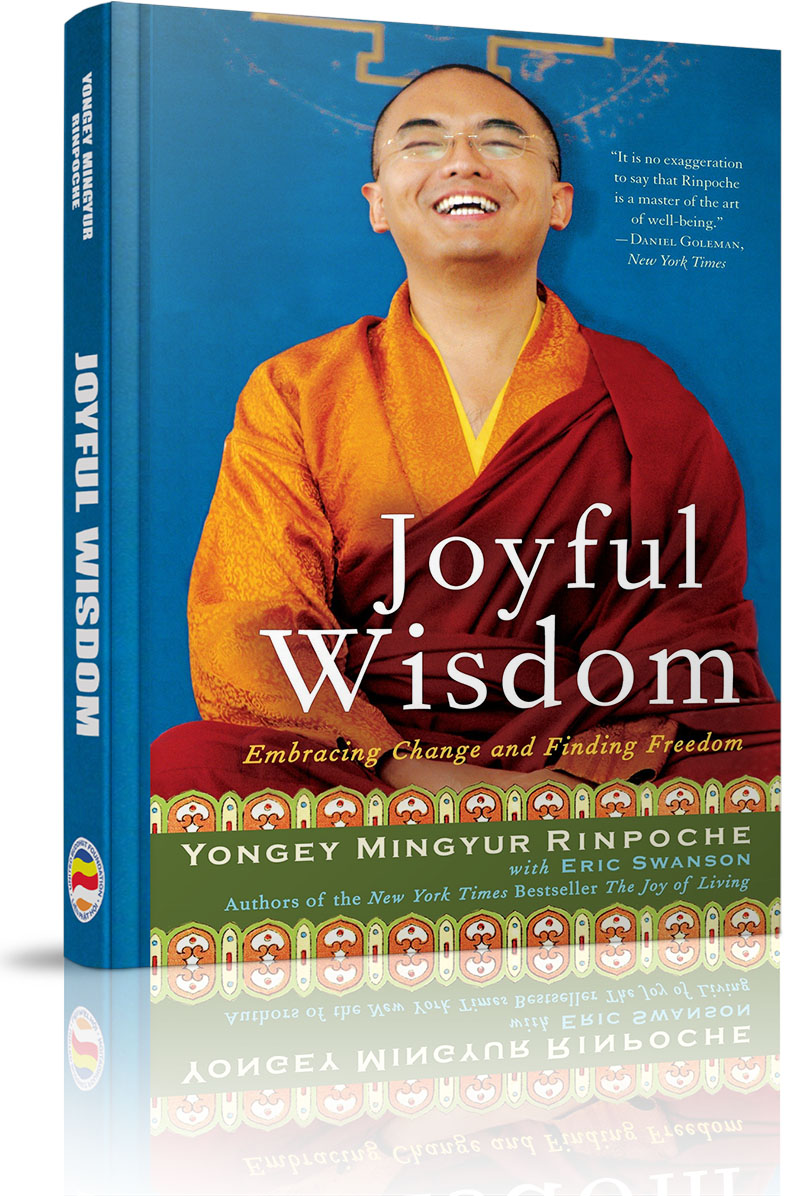

Trang chủ »» Danh mục »» THUYẾT GIẢNG GIÁO PHÁP »» Joyful Wisdom »» 5. Breaking through »»

Joyful Wisdom

»» 5. Breaking through

Xem Mục lục

Xem Mục lục  Vietnamese || Đối chiếu song ngữ

Vietnamese || Đối chiếu song ngữ

- Introduction

- Part One: Principles - 1. Light in the tunnel

- 2. The problem is the solution

- 3. The power of perspective

- 4. The turning point

- »» 5. Breaking through

- Part Two: Experience - 6. Tools of transformation

- 7. Attention

- 8. Insight

- 9. Empathy

- Part Three: Application – 10. Life on the path

- 11. Making it personal

- 12. Joyful wisdom

- none

—WILLIAM BLAKE, “The Marriage of Heaven and Hell”

IN THEIR WRITINGS and their teachings, Buddhist masters observe that all creatures want to attain happiness and avoid suffering. Of course, this observation is not confined to Buddhist teachings or to any particular philosophical, psychological, scientific, or spiritual discipline. It's a commonsense deduction based on looking at the way we and the other creatures with whom we share this world behave.

By now it should be clear that there are many varieties and degrees of suffering, all of which can be categorized as dukkha. But what is happiness? How can we define it? How can we attain it? Is there any one thing that everyone can agree on that makes us happy?

This last is a question I often ask when I teach, and the answers always vary. Some people say “Money.” Some people say “Love”. Some people say “Peace.” Some people say “Gold.” Once I even heard someone say “Chilies!”

What I find most interesting is that for every answer there's an opposite response. Some people don't want riches; they prefer to live simply. Some people prefer to live alone. Some people like to argue and fight for what they believe is right. And of course, some people don't like chilies.

After the answers stop coming, silence settles on the room, as everybody present realizes that there is no single thing that everyone can agree on. Gradually it begins to dawn on the people gathered in the room that the answers given represent either objects that exist outside or beyond themselves or conditions that are in some way other than what they experience right here, right now. At this point, the silence grows deeper and more contemplative as one by one, people begin to recognize that a simple question-and-answer exercise, conducted in a spirit of fun and often accompanied by laughter, has exposed deeply ingrained habits of perception and belief that are almost guaranteed to perpetuate suffering and inhibit the possibility of discovering an enduring, unconditional state of happiness.

Among these habits is the tendency to define our experience in dualistic terms: “self and “other”; “mine” and “not mine”; and “pleasant” and “unpleasant.” In itself, relating to the world dualistically isn't any great tragedy. In fact, as discussed earlier, we're biologically disposed and conditioned by our cultural, familial, and individual backgrounds to make distinctions—not only for their survival value but also for the role they play in social interaction and the performance of daily tasks. From a simply practical point of view, the ability to “map” and navigate our daily lives in dualistic terms is essential.

In talking to people over the years, however, I've encountered a common misconception that Buddhism considers dualistic perception as a kind of defect. That is not the case. Neither the Buddha nor any of the great masters who followed in his footsteps have said that there is something inherently wrong or harmful in relating to the world in dualistic terms. Rather, they explain, defining experience in terms of “subject” and “object,” “self and “other,” and so on, is simply one aspect of awareness: a useful, if limited, tool.

To use a very simple analogy, we can accomplish many tasks with our hands: typing, chopping vegetables, dialing telephone numbers, scrolling through the list of songs on an MP3 player, opening and closing doors, and buttoning shirts or blouses. You can probably add a long list of useful ways to use your hands. But would you be willing to say that whatever you can do with your hands represents your entire range of capabilities? Yes, if you work at it, you can probably walk on your hands. But can you see with them, hear with them, or smell with them? Can your hands digest food, maintain the functions of your heart or liver, or make decisions? Unless you've been gifted with unusual powers, the answer to these questions will be “no,” and you'd dismiss the idea that whatever your hands do represents the entire range of your capabilities.

While we can easily admit that our hands don't represent our entire range of abilities, it's a bit more difficult to recognize that splitting experience into opposing terms such as “subject” and “object,” “self and “other,” or “mine” and “not mine” represents only a fraction of the capacity of our buddha nature. Until we're introduced to the possibility of a different way of relating to experience, and embrace the possibility of exploring it, our dualistic perspective and the variety of mental and emotional habits that arise from it prevent us from experiencing the full range of our inherent potential.

DELUSION AND ILLUSION

Self-deception is a constant problem.

—Chogyam Trungpa, Cutting Through Spiritual Materialism, edited by John Baker and Marvin Casper

Imagine putting on a pair of dark green sunglasses. Everything you see would appear in shades of green: green people, green cars, green buildings, green rice, and green pizza. Even your own hands and feet would look green. If you took off your sunglasses, your entire experience would change. “Oh, people aren't green!” “My hands aren't green!” “My face isn't green!” “Pizza isn't green!”

But what if you never took off your sunglasses? What if you believed that you couldn't get through life without them, that you'd become so attached to wearing them that you'd never even consider taking them off, even when you went to bed? Certainly, you could get through life seeing everything in shades of green. But you'd miss out on seeing so many different colors. And once you became accustomed to seeing things in shades of green, you'd rarely pause to consider that green may not be the only color you could see. You'd begin to believe wholeheartedly that everything is green.

Similarly, certain mental and emotional habits condition our worldview. We become attached to a “sunglass point of view.” We believe that the way we see things is the way they truly are.

Our biology, culture, and personal experiences work together to mistake relative distinctions as absolute truths and concepts as direct experiences. This fundamental discrepancy almost invariably fosters a haunting sense of unease, a kind of “free-floating” dukkha lurking in the background of awareness as a nagging sense of in-completeness, isolation, or instability.

In an effort to combat this basic unease, we tend to invest the “inhabitants” of our relative or conditional world—ourselves, other people, objects, and situations—with qualities that enhance their semblance of solidness and stability. But this strategy clouds our perspective even further. In addition to mistaking relative distinctions as absolute, we bury this mistaken view in layers of illusion.

THE FIRST STEP

Suffering has good qualities.

—Engaging in the Conduct of Bodhisattvas,

translated by Khenpo Konchag Gyaltsen Rinpoche

The Fourth Noble Truth, the Truth of the Path, teaches us that in order to bring an end to suffering we need to cut through dualistic habits of perception and the illusions that hold them in place— not by fighting or suppressing them, but by embracing and exploring them. Dukkha, however it manifests, is our guide along a path that ultimately leads to discovering the source from which it springs. By facing it directly, we begin to use it, rather than be used by it.

At first, we might not see much more than a blur of thoughts, feelings, and sensations that all run together so fast and furiously that it's impossible to distinguish one from another. But with a bit of patient effort, well begin to make out an entire landscape of ideas, attitudes, and beliefs-most of which initially appear quite solid, sensible, and firmly rooted in reality. Yes, we might think, that's the way things are.

Yet as we continue to look, we start to notice a few cracks and holes. Maybe our ideas aren't as solid as we imagined. The longer we look at them, the more cracks we see, until eventually the whole set of beliefs and opinions on which we've based our understanding of ourselves and the world around us begins to crumble. Understandably, we may experience some confusion or disorientation as this happens. However, once the dust begins to settle, we find ourselves face-to-face with a much more direct and profound understanding of our own nature and the nature of reality.

Before setting out on the path, though, we might find it useful to familiarize ourselves with the terrain; not only to develop some idea of where we're going, but also to alert ourselves to “bumps”— fixed beliefs that are especially hard to penetrate—we're likely to hit along the way. As a young student at Sherab Ling, I was taught to look out for three such “bumps”' in particular: permanence, singularity, and independence.

PERMANENCE

Think that nothing lasts.

—Jamgon Kongtrul, The Torch of Certainty, translated by Judith Hanson

Cars and computers break down. People move away, change jobs, grow up, grow old, get sick, and eventually die. As we look at our experience, we can recognize that we're no longer infants or schoolchildren. We can see. and often welcome, other major transitions, like graduating from college, getting married, having children, and moving to a new home or a new job. Sometimes the changes we undergo aren't so pleasant. Like other people, we get sick, we grow old, and eventually we die. Maybe we lose our jobs or the person we're married to or romantically involved with announces “I don't love you anymore.”

Yet even as we acknowledge certain changes, on a very subtle level we cling to the idea of permanence: a belief that an essential core of “me, “others, and so on, remains constant throughout time. The “me” I was yesterday is the same “me” I am today. The table or book we saw yesterday is the same table or book we see today. The Mingyur Rinpoche who gave a talk yesterday is the same Mingyur Rinpoche giving a talk today. Even our emotions sometimes seem permanent: “I was angry at my boss yesterday, I'm angry at him today, and I'll be angry at him tomorrow. I'll never forgive him!”

The Buddha compared this delusion to climbing a tree that looks strong and whole on the outside but is hollow and rotten on the inside. The higher we climb, the more tightly we cling to the lifeless branches, and the more likely it is that one of those branches will break. Eventually, we must fall—and the pain of that fall will be greater the higher we climb.

On a mental and emotional level, for example, “you,” “me,” and other people are always changing. I can't say that the “me” I was at nine years old is the same “me” I was at nineteen, or even at thirty. The nine-year-old “me” was a child full of anxiety, frightened by loud noises, and terrified of being a failure in his father's eyes and in the eyes of his father's students. The nineteen-year-old “me” had graduated from two three-year retreat programs aimed at mastering the deeper practices of Tibetan Buddhist meditation, attending one monastic school while helping to build another, running the day-to-day functions of a large monastery in India, and teaching monks who were much older than he was. The thirty-three-year-old “me” spends a good deal of time in airports, traveling between many different countries, facing hundreds of people at a time in an attempt to deliver teachings and instructions at several different levels of sophistication; meeting in private with individuals or small groups of people who seek deeper insight into their personal practice; making international phone calls to plan a teaching tour for a year ahead; and learning bits and pieces of several different languages in order to make a connection with the people around the world. He also advises people from a wide variety of backgrounds in dealing with personal problems including chronic pain, depression, divorce, emotional and physical abuse, and the physical and emotional toll involved in caring for friends and family members who are ill or dying.

Similarly, “others” undergo mental and emotional changes. I've spoken to a number of people who are mystified by the fact that they can be talking one day to someone they know and everything seems fine. The other person is happy, looking forward to life, and ready to meet the challenges of the day. A day or maybe a week later, that same person is angry or depressed; he or she can't get out of bed or just can't see any hope in his or her life. Sometimes the changes are so dramatic—for example, as a result of alcoholism or some other addiction—we might find ourselves thinking, “I don't even recognize this person anymore!”

In addition, as I've learned through conversations with scientists over the years, our physical bodies are undergoing constant change on levels far below conscious awareness or control— producing hormones, for example, or regulating body temperature. By the time you've finished reading this sentence, some of the cells in your body have already have been eliminated and replaced by new ones. The molecules, atoms, and subatomic particles that make up those cells have shifted.

Even the molecules, atoms, and subatomic particles that make up this book—as well as the furniture in the room where you're reading it—are always shifting and changing, moving around. The pages of the book may start to yellow or wrinkle. Cracks may appear in the wall of your room. A bit of paint might chip off a nearby table.

Taking all these things into consideration, where can one find permanence?

SINGULARITY

Each moment is similar and because of the similarity, we are deluded.

—Gampopa, The Jewel Ornament of Liberation,

translated by Khenpo Kongchog Gyaltsen Rinpoche

From the delusion of permanence arises the idea of singularity— the belief that the “essential core” that persists through time is indivisible and uniquely identifiable. Even when we say things like “That experience changed me” or “I look at the world differently now,” we're still affirming a sense of “me” as a single whole, an inner “face” through which we gaze at the world.

Singularity is such a subtle delusion that it's hard to see until it's pointed out to us. For example, a woman recently confided, “I'm stuck in an impossible marriage. I loved my husband when I married him, but now I hate him. I have three children, though, and I don't want to put them through a long divorce battle. I want them to have a positive relationship with their lather. I don't want to move them from the house they've grown up in, but I don't want to rely on financial support from my husband.”

What's the word most frequently repeated in this series of statements?

“I.”

But who is “I”? Is “I” the person who loved her husband but now hates him? Is “I” the mother of three children who wants to avoid a long divorce battle or the woman who wants her children to develop a positive relationship with their father? How many “Is”' are there? One? Two? Three?

The likely response is that there's only one “I,” who reacts in different ways to different situations, who expresses different aspects of herself in relation to other people, or who—in response to new ideas and experiences, or changes in circumstances and conditions—has developed a different set of attitudes and feelings.

Given all these differences, can “I” really be one?

Similarly, we might ask ourselves if the “I” that responds in certain ways to a particular situation—an argument with a coworker or family member, perhaps- is the same “I” that responds in other ways to other situations, like reading a book, watching television, or checking e-mail.

Our tendency is to say, “Well, they're all parts of me.”

But if there are “parts,” can there be one?

INDEPENDENCE

Does the self exist within a name?

—Gampopa, The Jewel Ornament of Liberation, translated by Khenpo Kongchog Gyaltsen Rinpoche

Sometimes when I'm teaching, I ask people to play a sort of game, hiding most of my body behind my outer robe and just leaving my thumb sticking out. “Is this Mingyur Rinpoche?” I ask.

“No”, most people will reply.

So then I'll slick out my whole hand and ask, “How about this? Is this Mingyur Rinpoche?” Again, most people will say “No.”

If I stick out my arm and ask the same question, most people will also answer “No.”

But if I let my outer robe fall back into place so people can see my face, my arms, and so on, and ask the same question, the answer isn't always so clear. “Well, now that we can see all of you, that's Mingyur Rinpoche,” some people might say.

But this “all” is made of many different parts: thumbs, hands, arms, head, legs, heart, lungs, etc. And these parts are made up of smaller parts: skin, bone, blood vessels, and the cells that make them up; the atoms that make up the cells; and the particles that make up the atoms. Certain other factors, for example, the culture in which I was raised, the training I received, my experiences in retreat, and the conversations I've had with people around the world over the past twelve years could also be considered “parts” of “Mingyur Rinpoche.”

The place where someone is sitting in a public lecture room may also condition the way “Mingyur Rinpoche” appears. People sitting to the left or right may only see one side of him; people sitting directly in front may see his whole body; and people sitting in the back of the room may see a kind of a blurry image. Likewise, someone walking down the street may see “Mingyur Rinpoche” as “another of those smiling bald guys in red robes.” People who may be attending their first Buddhist teaching might see “Mingyur Rinpoche” as “a smiling bald guy in red robes who has some interesting ideas and a couple of good jokes.” Long-term students may see “Mingyur Rinpoche” as a reincarnated lama, spiritual guide, and personal advisor.

So while “Mingyur Rinpoche” may appear as an independent person, this appearance is made up of a lot of different parts and conditioned by a variety of circumstances. Like permanence and singularity, independence is a relative concept, a way of defining ourselves, other people, places, objects -even thoughts and emotions—as self-existing, self-contained “things-in-themselves.”

But we can see from our own experience that independence is an illusion. Would we say, for example, that we are our thumb? Our arm? Our hair? Are we the pain we might feel somewhere right now in our bodies, the illness we might be experiencing? Are we the person someone else sees walking down the street or sitting across from us at the dinner table?

Likewise, if we examine people, places, and objects around us, we can recognize that none of them are inherently independent, but made up of a number of different, interrelated parts, causes, and conditions. A chair, for instance, has to at least have legs and a kind of base on which to sit, a back we can lean against. Take away the legs or the seat or the back and it wouldn't be a chair, but a few pieces of wood or metal or whatever material the parts are made of. And this material, like parts of our bodies, is made up of molecules, atoms, subatomic particles that make up the atoms, and ultimately—from the perspective of modern physicists— packets of energy that make up subatomic particles.

All of these smaller parts, moreover, had to come together under the right circumstances to form the basic material that would be used to construct a chair. In addition, somebody—or more likely, more than one person—had to be involved in creating the different parts of the chair. Somebody had to cut down a tree for wood, for example, or gather the raw materials to create glass or metal, the fabric that covers the chair, and the stuffing that goes inside the fabric. Someone else had to shape all these materials and still others had to be involved in putting the parts together, assigning a price, shipping the completed chair to a store, and putting it on display. Then somebody had to buy it and move it to a home or office.

So even a simple object like a chair isn't an inherently existing “thing-in-itself,” but rather emerges from a combination of causes and conditions—a principle known in Buddhist terms as interdependence. Even thoughts, feelings, and sensations aren't things-in-themselves, but occur through a variety of causes and conditions. Anger or frustration might be traced back to a sleepless night, an argument, or pressure to meet a deadline. I've met a number of people who were physically or emotionally abused by their parents or other adults. “I'm a loser,” they'll sometimes say. “I'll never be able to find a good job or a lasting relationship.” “I wake up in a cold sweat some nights, and some days, when I see my manager approaching, my heart beats so hard I think it may punch right through my chest.”

Yet just as permanence has its advantages - inviting the possibility of changing jobs, for example, or recovering from an illness-interdependence can also work in our favor. One Canadian student of mine, acting on the advice of a friend, began attending a support group for adults who had been abused in one way or another as children. Over several months of discussing her own experiences and listening to other people describe theirs, the shame and insecurity that had haunted her for much of her life began to waver and then to lift. “For years, it was like listening to the same song over and over,” she later explained. “Now I can hear the whole CD.”

She hadn't studied Buddhism at all during this period. But with the help of her new friends, she'd uncovered an insight central to the Buddha's teachings.

EMPTINESS

There is nothing that can he described as either existing or not existing.

—The Third Karmapa,

Mahamudra: Boundless Joy and Freedom, translated by Maria Montenegro

During public teachings and private interviews, someone inevitably asks a big question. Though the words and phrasing vary from person to person, the essence is the same. “If everything is relative, impermanent, and interdependent, if nothing can be said to be definitely one thing or another, does that mean I'm not real? You're not real? My feelings aren't real? This room isn't real?”

There are four possible answers, simultaneously arising, equally true and false.

Yes.

No.

Yes and no.

Neither yes nor no.

Are you confused? Great! Confusion is a big break-through: a sign of cutting through attachment to a particular point of view and stepping into a broader dimension of experience.

Although the boxes in which we organize our experience—like “me,” “mine,” “self,” “other,” “subject,” “object,” “pleasant,” and “painful”—are inventions of the mind, we still experience “me-ness,” “other-ness,” “pain,” “pleasure,” and so on. We see chairs, tables, cars, and computers. We feel the joys and pangs of change. We get angry; we get sad. We seek happiness in people, places, and things, and try our best to shield ourselves from situations that cause us pain.

It would be absurd to deny these experiences. At the same time, if we begin to examine them closely, we can't point to anything and say “Yes! That's definitely permanent! That's singular! That's independent!”

If we continue breaking down our experiences into smaller and smaller pieces, investigating their relationships, looking for the causes and conditions that underlie other causes and conditions, eventually we hit what some people might call a “dead end.” It's not an end, though, and certainly not dead. It's our first glimpse of emptiness, the ground from which all experience emerges.

Emptiness, the main subject of the Second Turning of the Wheel of Dharma, is probably one of the most confusing terms in Buddhist philosophy. Even long-term students of Buddhism have a hard time understanding it. Maybe that's why the Buddha waited sixteen years after turning the First Wheel of Dharma to start talking about it.

Actually, it's pretty simple, once you get past your initial preconceptions about the meaning.

Emptiness is a rough translation of the Sanskrit term sunyata and the Tibetan term tongpa-nyi. The Sanskrit word sunya means “zero.” The Tibetan word tongpa means “empty”; nothing there. The Sanskrit syllable ta and the Tibetan syllabic nyi don't mean anything in themselves. But when added to an adjective or noun, they convey a sense of possibility or open-endedness. So when Buddhists talk about emptiness, we don't mean “zero,” but a “zero-ness”: not a thing in itself, but rather a background, an infinitely open “space” that allows for anything to appear, change, disappear, and reappear.

That's very good news.

If everything were permanent, singular, or independent, nothing would change. We'd be stuck forever as we are. We couldn't grow and we couldn't learn. No one and nothing could affect us. There would be no relation between cause and effect. We could press a light switch and nothing would happen. We could dip a bag of tea into a cup of hot water a million times, but the water wouldn't affect the tea and the tea wouldn't affect the water.

But that isn't the case, is it? If we press a button on a lamp, for example, the bulb lights up. If we dip a tea bag in a cup of hot water for a few moments, we end up with a delightful cup of tea. So to return to the questions regarding whether we are real, whether our thoughts and feelings are real, and whether the room in which we presently reside is real, we can answer “yes” in the sense that we experience these phenomena and “no” in the sense that if we look beyond these experiences we can't find anything that can be identified as inherently existing. Thoughts, feelings, chairs, chili peppers, the people in line at a grocery store-even the grocery store itself—can only be defined in comparison to something or someone else. They appear in our experience through the combination of many different causes and conditions. They are always in flux, constantly changing as they “collide” with other causes and conditions, which collide with other causes and conditions, on and on and on.

So on one hand we can't really say that anything we experience inherently exists. That's one way to look at emptiness. On the other hand, we can say that, since all of our experience emerges through the temporary collision of causes and conditions, there is nothing that is not emptiness.

In other words, the basic nature, or absolute reality, of all experience is emptiness. “Absolute,” however, does not imply something solid or permanent. Emptiness is, itself, “empty” of any definable characteristics: not zero, but not nothing. You could say that emptiness is an open-ended potential for any and all sorts of experience to appear or disappear—the way a crystal ball is capable of reflecting all sorts of colors because it is, in itself, free from any color.

Now, what does that imply about the “experiencer”?

BEING AND SEEING

To be absolutely nothing is to be everything.

—James W. Douglas, Resistance and Contemplation: The Way of Liberation

We wouldn't be able to experience all the wonders and terrors of phenomena if we didn't have the capacity to perceive them. All the thoughts, feelings, and other events we meet in daily life stem from a fundamental capacity to experience anything whatsoever. The qualities of buddha nature such as wisdom, capability, loving-kindness, and compassion have been described by the Buddha and the masters who followed him as “boundless,” “limitless,” and “infinite.” They are beyond conception but charged with possibility. In other words, the very basis of buddha nature is emptiness. But it isn't a zombie-like emptiness. Clarity, or what we might call a fundamental awareness that allows us to recognize and distinguish among phenomena, is also a basic characteristic of buddha nature, inseparable from emptiness. As thoughts, feelings, sensations, and so on, emerge, we become aware of them. The experience and the experiencer are one and the same. “Me' and the experience of “me” occur simultaneously, as do “other” and awareness of “other,” or “car” and the awareness of “car.”

Some psychologists refer to this as an “innocent perspective,” a raw awareness unchained by expectations or judgments, which can emerge spontaneously in the first few moments of visiting some huge place, like Yosemite National Park, the Himalayas, or the Potala Palace in Tibet. The panorama is so vast, you don't distinguish between "I" and “what I see.” There's just seeing.

It's commonly misunderstood, however, that in order to attain this innocent perspective, we somehow have to eliminate, suppress, or disengage from relative perception, and the hopes, fears, and other factors that support it. This is something of a misinterpretation of the Buddha's teachings. Relative perception is an expression of buddha nature, just as relative reality is an expression of absolute reality. Our thoughts, emotions, and sensations are like waves rising and falling in an endless ocean of infinite possibility. The problem is that we've become used to seeing only the waves and mistaking them for the ocean. Each time we look at the waves, though, we become a little more aware of the ocean- and as that happens, our focus begins to shift. We begin to identify with the ocean rather than the waves, watching them rise and fall without affecting the nature of the ocean itself. But that can only happen if we begin to look.

MOVING FORWARD

Exert yourself again and again in cutting through.

—-The Ninth Gyalwa Karmapa,

Mahamudra: The Ocean of Definitive Meaning, translated by Elizabeth M. Callahan

The Buddha was very skillful in presenting his “treatment plan” for dukkha. Though he never explicitly discussed emptiness or buddha nature in his teachings on the Four Noble Truths, he understood that cultivating an understanding of the basic issue of suffering and its causes—sometimes interpreted as relative wisdom— would eventually lead us to absolute wisdom: a profound insight into the basis, not only of experience, but also of the experiencer.

Relative wisdom, acknowledging limited and limiting beliefs and behaviors, is only part of the path of cessation: what you might call the “preparation stage.” In order to actually cut through our self-imposed limitations, we need to spend a little time observing our mental and emotional habits, befriending them, and perhaps discovering within our most challenging experiences a powerful company of bodyguards.

The exercises in the previous chapters offered a taste of the benefits we can experience through examining our thoughts, feelings, and situations. Part Two takes the process deeper, presenting in detail three transformative “tools” through which we can embrace the challenges and changes in our lives, and discover the seeds of courage, wisdom, and joy that lie within us, waiting to blossom.

MUA THỈNH KINH SÁCH PHẬT HỌC

DO NXB LIÊN PHẬT HỘI PHÁT HÀNH

Mua sách qua Amazon sẽ được gửi đến tận nhà - trên toàn nước Mỹ, Canada, Âu châu và Úc châu.

Quý vị đang truy cập từ IP 216.73.216.23, 69.15.33.77 và chưa ghi danh hoặc đăng nhập trên máy tính này. Nếu là thành viên, quý vị chỉ cần đăng nhập một lần duy nhất trên thiết bị truy cập, bằng email và mật khẩu đã chọn.

Chúng tôi khuyến khích việc ghi danh thành viên ,để thuận tiện trong việc chia sẻ thông tin, chia sẻ kinh nghiệm sống giữa các thành viên, đồng thời quý vị cũng sẽ nhận được sự hỗ trợ kỹ thuật từ Ban Quản Trị trong quá trình sử dụng website này.

Việc ghi danh là hoàn toàn miễn phí và tự nguyện.

Ghi danh hoặc đăng nhập

... ...

Trang chủ

Trang chủ