Bạn nhận biết được tình yêu khi tất cả những gì bạn muốn là mang đến niềm vui cho người mình yêu, ngay cả khi bạn không hiện diện trong niềm vui ấy. (You know it's love when all you want is that person to be happy, even if you're not part of their happiness.)Julia Roberts

Đừng cư xử với người khác tương ứng với sự xấu xa của họ, mà hãy cư xử tương ứng với sự tốt đẹp của bạn. (Don't treat people as bad as they are, treat them as good as you are.)Khuyết danh

Bất lương không phải là tin hay không tin, mà bất lương là khi một người xác nhận rằng họ tin vào một điều mà thực sự họ không hề tin. (Infidelity does not consist in believing, or in disbelieving, it consists in professing to believe what he does not believe.)Thomas Paine

Như cái muỗng không thể nếm được vị của thức ăn mà nó tiếp xúc, người ngu cũng không thể hiểu được trí tuệ của người khôn ngoan, dù có được thân cận với bậc thánh.Đức Đạt-lai Lạt-ma XIV

Với kẻ kiên trì thì không có gì là khó, như dòng nước chảy mãi cũng làm mòn tảng đá.Kinh Lời dạy cuối cùng

Cho dù không ai có thể quay lại quá khứ để khởi sự khác hơn, nhưng bất cứ ai cũng có thể bắt đầu từ hôm nay để tạo ra một kết cuộc hoàn toàn mới. (Though no one can go back and make a brand new start, anyone can start from now and make a brand new ending. )Carl Bard

Ðêm dài cho kẻ thức, đường dài cho kẻ mệt, luân hồi dài, kẻ ngu, không biết chơn diệu pháp.Kinh Pháp cú (Kệ số 60)

Không có sự việc nào tự thân nó được xem là tốt hay xấu, nhưng chính tâm ý ta quyết định điều đó. (There is nothing either good or bad but thinking makes it so.)William Shakespeare

Nếu bạn muốn những gì tốt đẹp nhất từ cuộc đời, hãy cống hiến cho đời những gì tốt đẹp nhất. (If you want the best the world has to offer, offer the world your best.)Neale Donald Walsch

Tinh cần giữa phóng dật, tỉnh thức giữa quần mê. Người trí như ngựa phi, bỏ sau con ngựa hènKinh Pháp cú (Kệ số 29)

Kẻ yếu ớt không bao giờ có thể tha thứ. Tha thứ là phẩm chất của người mạnh mẽ. (The weak can never forgive. Forgiveness is the attribute of the strong.)Mahatma Gandhi

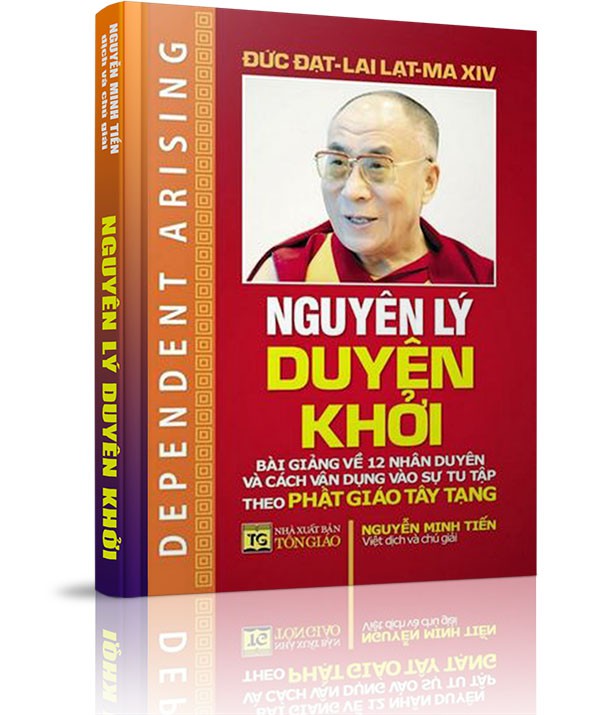

Trang chủ »» Danh mục »» TỦ SÁCH RỘNG MỞ TÂM HỒN »» Dependent Arising »» Practice of the Six Perfections »»

Xem Mục lục

Xem Mục lục  Vietnamese || Đối chiếu song ngữ

Vietnamese || Đối chiếu song ngữ

DO NXB LIÊN PHẬT HỘI PHÁT HÀNH

Mua sách qua Amazon sẽ được gửi đến tận nhà - trên toàn nước Mỹ, Canada, Âu châu và Úc châu.

Quý vị đang truy cập từ IP 216.73.216.157 và chưa ghi danh hoặc đăng nhập trên máy tính này. Nếu là thành viên, quý vị chỉ cần đăng nhập một lần duy nhất trên thiết bị truy cập, bằng email và mật khẩu đã chọn.

Chúng tôi khuyến khích việc ghi danh thành viên ,để thuận tiện trong việc chia sẻ thông tin, chia sẻ kinh nghiệm sống giữa các thành viên, đồng thời quý vị cũng sẽ nhận được sự hỗ trợ kỹ thuật từ Ban Quản Trị trong quá trình sử dụng website này.

Việc ghi danh là hoàn toàn miễn phí và tự nguyện.

Ghi danh hoặc đăng nhập