Chúng ta phải thừa nhận rằng khổ đau của một người hoặc một quốc gia cũng là khổ đau chung của nhân loại; hạnh phúc của một người hay một quốc gia cũng là hạnh phúc của nhân loại.Đức Đạt-lai Lạt-ma XIV

Ai sống một trăm năm, lười nhác không tinh tấn, tốt hơn sống một ngày, tinh tấn tận sức mình.Kinh Pháp cú (Kệ số 112)

Như đá tảng kiên cố, không gió nào lay động, cũng vậy, giữa khen chê, người trí không dao động.Kinh Pháp cú (Kệ số 81)

Hạnh phúc không phải là điều có sẵn. Hạnh phúc đến từ chính những hành vi của bạn. (Happiness is not something ready made. It comes from your own actions.)Đức Đạt-lai Lạt-ma XIV

Điều người khác nghĩ về bạn là bất ổn của họ, đừng nhận lấy về mình. (The opinion which other people have of you is their problem, not yours. )Elisabeth Kubler-Ross

Khởi đầu của mọi thành tựu chính là khát vọng. (The starting point of all achievement is desire.)Napoleon Hill

Hạnh phúc không tạo thành bởi số lượng những gì ta có, mà từ mức độ vui hưởng cuộc sống của chúng ta. (It is not how much we have, but how much we enjoy, that makes happiness.)Charles Spurgeon

Phán đoán chính xác có được từ kinh nghiệm, nhưng kinh nghiệm thường có được từ phán đoán sai lầm. (Good judgment comes from experience, and often experience comes from bad judgment. )Rita Mae Brown

Hãy tin rằng bạn có thể làm được, đó là bạn đã đi được một nửa chặng đường. (Believe you can and you're halfway there.)Theodore Roosevelt

Nhiệm vụ của con người chúng ta là phải tự giải thoát chính mình bằng cách mở rộng tình thương đến với muôn loài cũng như toàn bộ thiên nhiên tươi đẹp. (Our task must be to free ourselves by widening our circle of compassion to embrace all living creatures and the whole of nature and its beauty.)Albert Einstein

Như bông hoa tươi đẹp, có sắc lại thêm hương; cũng vậy, lời khéo nói, có làm, có kết quả.Kinh Pháp cú (Kệ số 52)

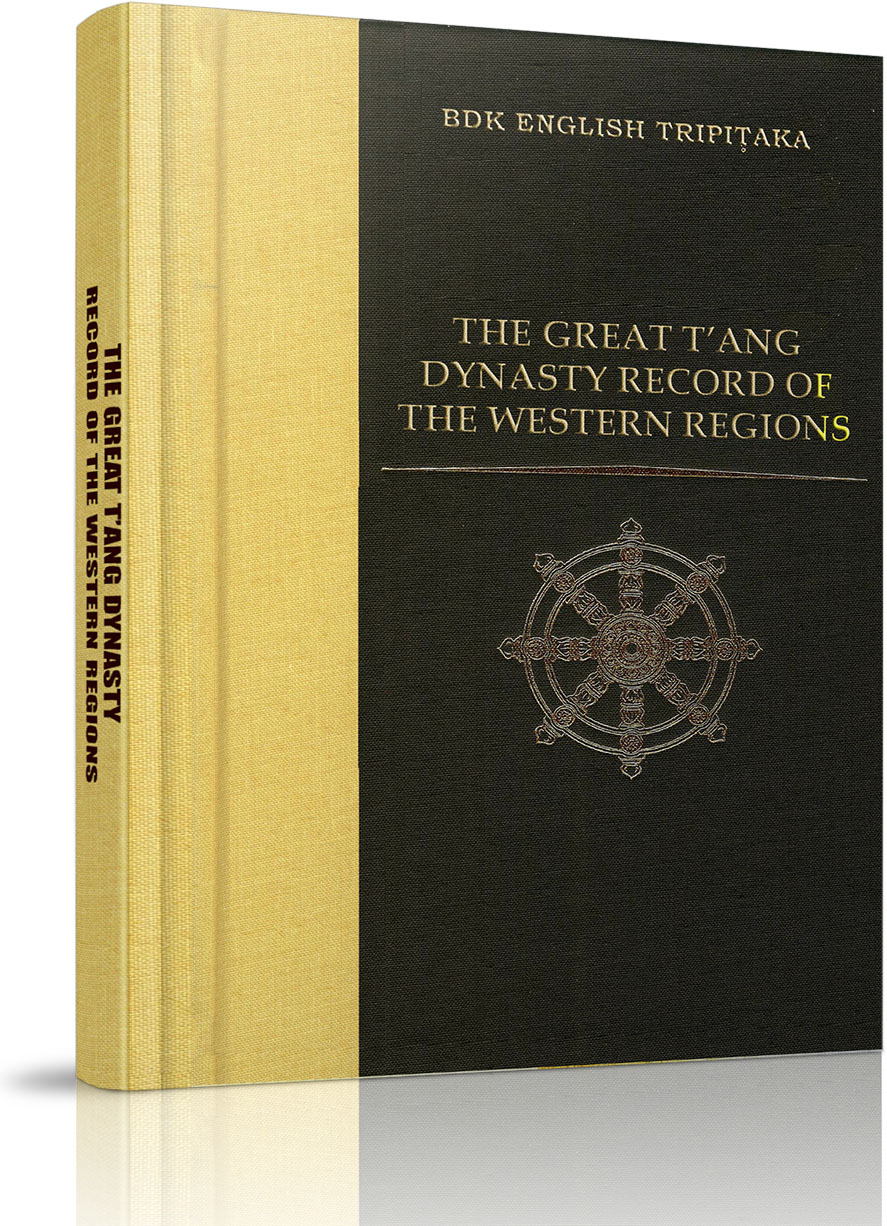

Trang chủ »» Danh mục »» »» The Great Tang Dynasty Record of the Western Regions »» Fascicle II »»

The Great Tang Dynasty Record of the Western Regions

»» Fascicle II

1. The Country of Lampa

2. The Country of Nagarahara

3. The Country of Gandhara

In a careful study we find that Tianzhu is variantly designated, causing much confusion and perplexity. Formerly it was called Shengdu, or Xiandou, but now we should call it Indu (India) according to the right pronunciation.

The people of India use different names for their respective countries, while people of distant places with diverse customs generally designate the land that they admire as India.

The word indu means “moon,” which has many names, and this is one of them. It means that living beings live and die in the wheel of transmigration in the long night of ignorance ceaselessly, without a rooster to announce the advent of the dawn. When the sun has sunk candles continue to give light in the night. Although the stars are shining in the sky, how can they be as brilliant as the clear moon? For this reason India was compared to the moon. Because saints and sages emerged one after another in that land to guide living beings and regulate all affairs, just as the moon shines upon all things, it was called India.

In India the people are divided into different castes and clans, among whom the brahmans are the noblest. Following their good name, tradition has designated the whole land as the brahmanical country, disregarding the regular lines of demarcation.

As regards the territory, we may say that the whole of India, with its five parts, is over ninety thousand li in circuit, with three sides facing the sea and the Snow Mountains at its back in the north. It is wide in the north and narrow in the south, in the shape of a crescent moon. The land is divided into more than seventy countries. The climate is particularly hot and the soil is mostly moist, with many springs. In the north there are many mountains and the 875c hills are of saline-alkaline soil. In the east the plain is rich and moist, and the cultivated fields are productive. In the south vegetation is luxuriant, while in the west the soil is hard and barren. Such is the general condition [of this vast country] told in brief.

For the measurement of space there is the yojana. (In olden times it was called youxiin, yiizhena, oryouyan, all incorrect.) One yojana is the distance covered by the ancient royal army in one day’s time. Formerly it was said to be forty li, or thirty li according to Indian usage, while in Buddhist texts it was counted as only sixteen li.

To divide it down to the infinitesimal, one yojana is divided into eight krosas, one krosa being the distance within which the mooing of a bull can be heard, one krosa into five hundred bows, one bow into four cubits, one cubit into twenty-four fingers, and one finger joint into seven grains of winter wheat.

Then the division goes on by sevens through the louse, the nit, the crevice dust, the ox hair, the sheep wool, the hare hair, the copper dust [particle], the water dust, down to the fine dust, and one fine dust [particle] is divided into seven extremely fine dust [particles]. The extremely fine dust is indivisible; if divided it becomes emptiness. This is why it is called extremely fine dust.

Although the names of the alternating [periods of] day and night and the emergence and disappearance of the sun and moon are different [from those used in China], there is no difference in the measurement of time and season. The months are named according to the position of the Big Dipper.

The briefest unit of time is called a ksana; one hundred twenty ksanas make one tatksana; sixty tatksanas make one lava; thirty lavas make one muhiirta; five muhurtas make one kola; and six kolas make one day and one night (three kolas in the daytime and three in the night). Secular people divide one day and one night into eight kolas (four kolas in the daytime and four in the night, each being subdivided into four divisions).

From the waxing moon to the full moon is known as the white division, and from the waning moon to the last day of the month is called the black division. The black division has fourteen or fifteen days, as the month may be “small” or “big.” The anterior black division and the posterior white division constitute one month and six months make one year. When the sun moves inside the celestial equator, it is the northern revolution, and when it moves outside the celestial equator, it is the southern revolution. These two revolutions constitute one year. The year is also divided into six seasons, namely,

from the sixteenth day of the first month to the fifteenth day of the third month is the season of gradual heat;

from the sixteenth day of the third month to the fifteenth day of the fifth month is the season of intense heat;

from the sixteenth day of the fifth month to the fifteenth day of the seventh month is the rainy season;

from the sixteenth day of the seventh month to the fifteenth day of the ninth month is the season of exuberance;

from the sixteenth day of the ninth month to the fifteenth day of the eleventh month is the season of gradual cold;

and from the sixteenth day of the eleventh month to the fifteenth day of the first month is the season of severe cold.

According to the holy teachings of the Tathagata, a year is divided into three seasons, namely

from the sixteenth day of the first month to the fifteenth day of the fifth month is the hot season;

from the sixteenth day of the fifth month to the fifteenth day of the ninth month is the rainy season;

and from the sixteenth day of the ninth month to the fifteenth day of the first month is the cold season.

Or it is divided into four seasons, namely, spring, summer, autumn, and winter.

The three months of spring are called Caitra, Vaisakha, and Jyestha, corresponding to the period from the sixteenth day of the first month to the fifteenth day of the fourth month in China.

The three months of summer are called Asadha, Sravana, and Bhadrapada, corresponding to the period from the sixteenth day of the fourth month to the fifteenth day of the seventh month in China.

The three months of autumn are known as Asvayuja, Karttika, and Margaslrsa, corresponding to the period from the sixteenth day of the seventh month to the fifteenth day of the tenth month in China.

The three months of winter are named Pausa, Magha, and Phalguna, corresponding to the period from the sixteenth day of the tenth month to the fifteenth day of the first month in China.

Thus, according to the holy teachings of the Buddha, the monks of India observe the summer retreat during the rainy season, either in the earlier three months or in the later three months. The earlier three months correspond to the period from the sixteenth day of the fifth month to the fifteenth day of the eighth month in China, and the later three months correspond to the period from the sixteenth day of the sixth month to the fifteenth day of the ninth month in China.

Former translators of scriptures and Vinaya texts used the terms zuoxia or zuola (“to sit for the summer or the annual retreat”). This was because they were outlandish people who did not understand the Chinese language correctly or were not conversant with the dialects, and so they committed mistakes in their translations.

Moreover, there are divergences in the calculation of the dates of the Buddha’s entry into his mother’s womb, birth, renunciation, enlightenment, and nirvana; this point will be discussed later.

As regards the towns and cities, they have square city walls, which are broad and tall. The streets and lanes are narrow and winding, with stores facing the roads and wine shops standing beside the streets. Butchers, fishermen, harlots, actors, executioners, and scavengers mark their houses with banners and are not allowed to live inside the cities. When they come to town they have to sneak up and down along the left side of the road.

Concerning the building of residential houses and the construction of the city walls, they are mostly built with bricks, as the terrain is low and humid, while the walls of houses may be made of wattled bamboo or wood. The roofs of houses, terraces, and pavilions are made of planks, plastered with limestone and covered with bricks or adobe. Some of the lofty buildings are similar in style to those in China.

Cottages thatched with cogon grass or ordinary straw are built with bricks or planks and the walls are adorned with limestone. The floor is purified by smearing it with cow dung and seasonal flowers are scattered over it. In this matter they differ [from Chinese custom].

The monasteries are constructed in an extremely splendid manner. They have four corner towers and the halls have three tiers. The rafters, eaves, 876b ridgepoles, and roof beams are carved with strange figures. The doors, windows, and walls are painted with colored pictures.

The houses of the common people are ostentatious inside but plain and simple outside.

The inner chambers and main halls vary in their dimensions and the structures of the tiered terraces and multistoried pavilions have no fixed style,

but the doors open to the east and the throne also faces east. For a seat on which to rest a rope bed (charpoy) is used. The royal family, great personages, officials, commoners, and magnates adorn their seats in different ways, but the structure is the same in style. The sovereign’s throne is exceedingly high and wide and decorated with pearls. Called the lion seat, it is covered with fine cotton cloth and is mounted by means of a jeweled footstool. The ordinary officials carve their seats in different decorative patterns according to their fancy and they ornament them with rare gems.

Both the upper [clothes] and undergarments, as well as ornamental garb, need no tailoring. Pure white is the preferred color, while motley is held in no account. The men wind a piece of cloth around the waist under the armpits and leave the right shoulder uncovered. The women wear a cape that covers both shoulders and hangs down loose. The hair on the top is combed into a small topknot with the rest of the hair falling down. Some men clip their mustaches and have other strange fashions, such as wearing a garland on the head or a necklace on the body.

For clothing they use kauseya and cotton cloth, kauseya being silk spun by wild silkworms. The ksauma (linen) cloth is made of hemp or similar fibers. The kambala is woven with fine sheep wool, while the helci cape (a sort of raincoat?) is woven with the wool of a wild animal.

As this wool is fine and soft and can be spun and woven, it is valued for making garments.

In North India, where the climate is bitterly cold, the people wear tight- fitting short jackets, quite similar to those of the Hu people. The costumes of the heretics vary in style and are strangely made. They dress in peacock tails, or wear necklaces of skulls, or go naked, or cover their bodies with grass or boards, or pluck their hair and clip their mustaches, or have disheveled hair with a small topknot. Their upper [clothes] and undergarments have no fixed style and the color may be red or white; there is no definite rule.

The monks have only the three regular robes, [the samghati,] the samkaksika, and the nivasana robes as their religious garments. The different sects have different ways of making the three robes, of which the fringes may be broad or narrow and the folds may be small or large.

The samkaksika (known in Chinese as “armpit cover” and formerly transcribed as sengqizhi incorrectly) covers the left shoulder and veils both armpits. It is open on the left and closed on the right side, reaching below the waist.

Since the nivasana (known in Chinese as “skirt” and formerly transcribed as niepanseng incorrectly) has no strings for fastening; it is worn by gathering it into pleats, which are tightened with a braid. The pleats are folded in different ways by different sects and the color also differs, either yellow or red.

People of the ksatriya (military and ruling class) and the brahman (priestly class) castes are pure and simple in lodging and clean and frugal. The dress and ornaments of the kings and ministers are very ostentatious. Garlands and coronets studded with gems are their headdresses, and rings, bracelets, and necklaces are their bodily ornaments. The wealthy merchants use only bracelets.

Most people go barefoot; few wear shoes. They stain their teeth red or black, have closely

876c cropped hair, pierce their earlobes, and have long noses and large eyes. Such are their outward features.

They voluntarily keep themselves pure and clean, not by compulsion. Before taking a meal they must wash their hands. Remnants and leftovers are not to be served again and food vessels are not passed from one person to another. Earthenware and wooden utensils must be discarded after use, and golden, silver, copper, or iron vessels are polished each time after use.

When the meal is over they chew willow twigs to cleanse [their mouths], and before washing and rinsing their mouths they do not come into contact with one another. Each time after going to defecate or urinate they must wash themselves and daub their bodies with a fragrant substance, such as sandalwood or turmeric. When the monarch is going to take a bath music made by beating drums and playing stringed instruments is performed, along with singing. Before offering sacrifices to gods and worshiping at temples they take baths and wash themselves.

It is known that their writing, composed of forty-seven letters, was invented by the deva Brahma as an original standard for posterity. These letters are combined to indicate objects and used as expressions for events. The original [language] branched as it gradually became widely used, and there are slight modifications of it according to place and people. As a language in general, it did not deviate from the original source.

The people of Central India are particularly accurate and correct in speech, and their expressions and tones are harmonious and elegant like the language of the devas. They speak accurately in a clear voice and serve as a standard for other people. The people of neighboring lands and foreign countries became accustomed to speaking in erroneous ways until their mistakes became accepted as correct, and they vied with one another in emulating vulgarities, not sticking to the pure and simple style.

As regards their records of sayings and events, there are separate departments in charge of them. The annals and royal edicts are collectively called Nilapila (Blue Collection), in which good and bad events are recorded, and calamities as well as auspicious signs are noted down in detail.

To begin the education of their children and induce them to make progress, they first guide them to learn the Book of Twelve Chapters; and when the children reach the age of seven, the great treatises of the five knowledges are gradually imparted to them. The first is the knowledge of grammar, which explains the meanings of words and classifies them into different groups. The second is the knowledge of technical skills, which teaches arts and mechanics, the principles of yin and yang (negativity and positivity), and calendrical computation. The third is the knowledge of medicine, including the application of incantation, exorcism, drugs, stone needles, and moxibustion. The fourth is the knowledge of logic, by which orthodox and heterodox are ascertained and truth is differentiated from falsehood. The fifth is the inner knowledge, which thoroughly investigates the teachings of the five vehicles and the subtle theory of cause and effect.

The brahmans study the Four Vedas (formerly transcribed as Pituo incorrectly). The first treatise is on longevity, dealing with the preservation of good health and the readjustment of mentality. The second is on worship, that is, offering sacrifices and saying prayers. The third is on equity, concerning ceremonial rituals, divination, military tactics, and battle formation. The fourth is on practical arts, which teaches unusual abilities, crafts and numeration, incantation, and medical prescriptions.

The teachers must be learned in the essence [of these treatises] and thoroughly master the profound mysteries. They expound the cardinal principles [to the pupils] and teach them with succinct but penetrating expressions. The teachers summon up their pupils’ energy to study and tactfully induce them to progress. They instruct the dull and encourage the less talented. Those disciples who are intelligent and acute by nature and have sensible views, intending to live in seclusion, confine themselves, and lock the door against the outside until they complete their studies. On reaching the age of thirty, they have fixed their minds and gained achievements in learning. After having been appointed to official posts, the first thing they do is to repay the kindness of their teachers.

There are some people who are conversant with ancient lore and fond of classic elegance, living in seclusion to preserve their uprightness. They drift along the course of life without worldly involvement and remain free and unfettered, above human affairs. They are indifferent to honor and humiliation and their renown spreads far. The rulers, even while treating such people with courtesy, cannot win them over to serve at court.

But the state honors wise and learned people and the [common] people respect those who are noble and intelligent, according them high praise and treating them with perfect etiquette. Therefore people can devote their attention to learning without feeling fatigue and they travel about seeking knowledge and visiting masters of the Way in order to rely on the virtuous ones, not counting a thousand li as a long journey.

Although their families may be rich, such people make up their minds to live wandering about the world, begging for their food wherever they go. They value the acquisition of truth and do not deem poverty a disgrace.

Those people who lead a life of amusement and dissipation, eating delicious food and wearing expensive garments, neither have virtue nor study constantly; they incur shame and disgrace upon themselves and their ill repute spreads far and wide.

The Tathagata’s teachings may be comprehended by each listener according to his own type of mentality, and as we are now far away from the time of the holy Buddha some of his right Dharma is still pure and some has become defiled. With the faculty of understanding all people can acquire the enlightenment of wisdom. There are different sects, like peaks, standing against each other and debating various viewpoints, as vehemently as crashing waves. They study divergent specific subjects but they all lead to the same goal. Each of the eighteen sects is expert in argumentation, using sharp and incisive words. The manner of living of the Mahayana (Great Vehicle) followers and that of the Hinayana (Small Vehicle) followers differ from each other. They engage themselves in silent meditation, or in walking to and fro, or in standing still. Samadhi (intense mental concentration) and prajhci (wisdom) are far apart and noisiness and calmness are quite different. Each community of monks has laid down its own restrictive rules and regulations.

All texts, whether belonging to the Vinaya (disciplinary rides), the Abhidharma (treatises), or the Sutras (discourses), are scriptures of the Buddha. A monk who can expound one text is exempted from routine monastic duties. One who can expound two texts is supplied with additional good rooms and daily requisites. One who can expound three texts is to be served by attendants. One who can expound four texts is provided with lay servants at his service. One who can expound five texts is entitled to ride an elephant when going out. One who can expound six texts has a retinue protecting him.

The honor given to those who have high morality is also extraordinary.

Assemblies for discussion are often held to test the intellectual capacity of the monks, in order to distinguish superior from inferior, and to reject the dull and promote the bright.

Those who can deliberate on the subtle sayings and glorify the wonderful theories with refined diction and quick eloquence may ride richly caparisoned elephants, with hosts of attendants preceding and following behind them.

But those to whom the theories are taught in vain, or who have been defeated in a debate, explaining few principles in a verbose way or distorting the teachings with language that is merely pleasant to the ear, are daubed with ocher or chalk on the face while dust is scattered over the body, and they are exiled to the wilderness or discarded in ditches.

In this way the good and the evil are distinguished and the wise and the ignorant disclosed. Thus people may take delight in the Way and study diligently at home. They may either forsake their homes or return to secular life, as they please.

To those who commit faults or violate the disciplinary rules, the community of monks may mete out punishments. A light offense incurs public reprimand, and the penalty for the next gravest offense is that the monks do not speak to the offender. One who has committed a grave offense is excommunicated; that is, he is expelled contemptuously by the community of monks. Once expelled the offender will have nowhere to take shelter and will suffer the hardships of a vagabond life, or he may return to his former life as a layperson.

As far as the different clans are concerned, there are four castes among the people. The first caste is that of the brahmans, who are pure in conduct, adhere to their doctrines, live in chastity, and preserve their virtue in purity. The second is the caste of ksatriyas (formerly transcribed incorrectly as chali), who are royal descendants and rule the country, taking benevolence and humanity as their objects in life. The third is the caste of vaisyas (formerly transcribed incorrectly as pishe), who are merchants and traders, exchanging goods to meet the needs of one another and gaining profit far and near. The fourth caste is the siidras, farmers who labor in the fields and toil at sowing and reaping.

These four castes are differentiated by their hereditary purity or defilement. People of a given caste marry within the caste and the conspicuous and the humble do not marry each other. Relatives, either on the father’s or the mother’s side, do not intermarry. A woman can marry only once and can never remarry.

There are numerous miscellaneous clans grouped together according to their [professional] categories, and it is difficult to give a detailed account.

The monarchs and kings of successive generations have always been ksatriyas. When usurpation and regicide occasionally happened, other families assumed supreme power.

The warriors of the nation are well-chosen men of extraordinary bravery and, as the occupation is hereditary, they become experienced in the art of war. In peacetime they guard the palace buildings and in times of war they courageously forge ahead as the vanguard.

The army is composed of four types of troops, namely, infantry, cavalry, charioteers, and elephant-mounted soldiers. The war elephant is covered with strong armor and its tusks are armed with sharp barbs. The general who controls the armed forces rides on it, with two soldiers walking on each side to manage the animal. The chariot carrying the commander-in-chief is drawn by four horses and arrays of soldiers march beside the wheels to protect him. The cavalrymen spread open to draw up a defensive formation or gallop ahead to pursue the defeated enemy. The infantry, daring men chosen for their boldness, go lightly into battle, carrying large shields and long spears, sabers, or swords and dashing to the front of the battle array. All their weapons are sharp and keen and they have been trained in such weaponry as the spear, shield, bow and arrow, saber, sword, battle axe, hatchet, dagger axe, long pole, long spear, discus, rope, and the like, with which they practice generation after generation.

Although the people are violent and impetuous by temperament they are plain and honest in nature. They never accept any wealth without considering the propriety of the action but give others more than what is required by righteousness. They fear retribution for sins in future lives and make light of the benefits they enjoy in the present. They do not engage in treachery and are creditable in keeping their promises.

Government administration emphasizes simplicity and honesty and the people are amicable by social custom. There are occasionally criminals and scoundrels who violate the national law or scheme to endanger the sovereign. When the facts are discovered these criminals are often cast into jail, where they are left to live or die; they are not sentenced to death but are no longer regarded as members of human society.

The punishment for those who infringe the ethical code or behave against the principles of loyalty and filial piety is to cut off the nose, excise an ear, mutilate a hand, or amputate a foot, or the offender may be banished to another country or into the wilderness. Other offenses can be expiated by a cash payment.

When a judge hears a case no torture is inflicted upon the accused to extort a confession. The accused answers whatever questions are put to him and then a sentence is fairly passed, according to the facts. There are some who refuse to admit their unlawful activities, ashamed of their faults, or who try to cover up their mistakes. In order to ascertain the actual facts of a case ordeals are required to justify a final judgment. There are four ways, namely, ordeals by water, fire, weighing, and poison.

In the ordeal by water the accused person is put into a sack and a stone is put into another sack; the two sacks are connected together and thrown into a deep river to discriminate the real criminal from the suspect. If the person sinks and the stone floats his guilt is proven, but if the person floats and the stone sinks he is then judged as having concealed nothing.

In the ordeal by fire the accused is forced to crouch on a piece of hot iron and required to stamp on it with his feet, to touch it with his hands, and to lick it with his tongue. If the charge against him is false he will not be harmed, but if he is burned he is judged to be the real culprit. If a weak and feeble person cannot stand the heat of the scorching iron, he is asked to scatter some flower buds over the hot iron. If he is falsely charged the buds open into flowers, but if he is truly a criminal the buds are burned.

In the ordeal by weighing the accused is weighed on a balance against a stone to determine which is heavier. If the charge is false the person goes down, while the stone goes up; if the charge is true the stone is weightier than the person.

In the ordeal by poison the right hind leg of a black ram is cut and poison is put into it as a portion for the accused to eat. If the charge is true the person dies from the poison, but if the charge is false the poison is counteracted and the accused may survive.

These four ordeals are the methods for the prevention of a hundred misdeeds.

There are nine grades in the manner of paying homage. They are (1) inquiring after one’s health, (2) bowing down three times to show respect, (3) bowing with hands raised high, (4) bowing with hands folded before the chest, (5) kneeling on one knee, (6) kneeling on both knees, (7) crouching with hands and knees on the ground, (8) bowing down with hands, elbows, and head to the ground, and (9) prostrating oneself with hands, elbows, and head touching the ground.

In all these nine grades the utmost veneration is expressed by doing only one obeisance. To kneel down and praise the other’s virtue is the perfect form of veneration. If one is at a distance [from the venerated person], one just prostrates with folded hands. If a venerated person is nearby, one kisses their feet and rubs their heels.

When one is delivering messages or receiving orders, he must hold up his robe and kneel.

The honored person who receives veneration must say some kind words in return, or stroke the head or pat the back of the worshiper, giving him good words of admonition to show his affection and kindness. When a homeless monk receives salutation he expresses only his good wishes in return and never stops the worshiper from paying homage to him.

One often pays reverence to a great respected master by circumambulating him once, thrice, or as many times as one wishes if one has a special request in mind.

When a person is sick he refrains from eating food for seven days, and during this period he may often recover his health. If he is not cured then he takes medicine. Medicines are of various properties and have different names, and physicians differ in medical technique and methods of diagnosis.

At a funeral ceremony the relatives of the departed one wail and weep, rend their clothes and tear their hair, strike their foreheads, and beat their chests. They do not wear mourning clothes and have no fixed period of mourning. There are three kinds of burial service. The first is cremation, in which a pyre is built and the body is burned. The second is water burial, in which the corpse is put into a stream to be carried away. The third is wilderness burial, in which the body is discarded in a forest to feed wild animals.

After the demise of a king, the first function is to enthrone the crown prince so that he may preside over the funeral ceremony and fix the positions of superiority and inferiority. Meritorious titles are conferred on a king while 878a he is living and no posthumous appellations are given after his death.

No one goes to take a meal at a house where the people are suffering the pain of bereavement, but when the funeral service is over things go back to normal and there are no taboos. Those who have taken part in a funeral procession are considered unclean and they must all bathe themselves outside the city before reentering the city walls.

As regards those who are getting very old, approaching the time of death, suffering from incurable disease, or fearing that life is drawing to an end, they become disgusted with this world, desire to cast off human life, despise mortal existence, and wish to get rid of the ways of the world. Their relatives and friends then play music to hold a farewell party, put them in a boat, and row them to the middle of the Ganges River so that they may drown themselves in the river. It is said that they will thus be reborn in the heavens. Out of ten people only one cherishes such ideas, and so far I have not seen this with my own eyes.

According to monastic regulations, homeless monks should not lament over the deaths of their parents but should recite and chant scriphires in memory of their kindness, so as to be in keeping with the funeral rites and impart happiness to the departed souls.

As the government is liberal official duties are few. There is no census registration and no corvee labor is imposed upon the people. Royal lands are roughly divided into four divisions. The first division is used by the state to defray the expense of offering sacrifices to gods and ancestors, the second division is used for bestowing fiefs to the king’s assistants and ministers, the third division is for giving rewards to prominent and intelligent scholars of high talent, and the fourth division is for making meritorious donations to various heterodox establishments. Therefore taxation is light and forced labor rarely levied. Everyone keeps to his hereditary occupation and all people cultivate the portions of land allotted to them per capita. Those who till the king’s fields pay one-sixth of their crops as rent.

Also, in order to gain profits merchants and traders travel about exchanging commodities and they pay light duties at ferries and barriers to pass through.

For public construction no forced labor is enlisted; laborers are paid according to the work they have done.

Soldiers are dispatched to garrison outposts and palace guards are conscripted according to circumstances, and rewards are announced in order to obtain applicants.

Magistrates and ministers, as well as common government officials and assistants, all have their portions of land so that they may sustain themselves by the fief they have been granted.

As the climate and soil vary in different places, the natural products also differ in various districts. There are diverse descriptions of flowers, herbs, fruit, and trees with different names, such as amra (mango), dmla (tamarind), madhiika (licorice), badara (jujube), kapittha (wood apple), amalaka (myrobalan), tinduka (Diospyros), udumbara (Ficus glomerat a), moca (plantain), narikera (coconut), andpanasa (jackfruit). It is difficult to give a full list of such fruit [frees], and here I just mention a few of them that are valued by the people. Dates, chestnuts, and green and red persimmons are unknown in India. Pears, crabapples, peaches, apricots, and grapes are often alternately grown in Kasmtra and elsewhere, while pomegranates and sweet oranges are planted in all countries.

In the cultivation of fields, such farm work as sowing and reaping, ploughing and weeding, and seeding and planting are done according to the seasons, either laboriously or with ease. Among the native products, rice and wheat are particularly abundant. As for vegetables, there are ginger, mustard, melon, calabash, and kanda (beet). Onion and garlic are scarce and few people eat them. Those who eat them are driven out of the city.

Milk, ghee, oil, butter, granulated sugar, rock candy, mustard-seed oil, 878b and various kinds of cakes and parched grainse are used as common food, and fish, mutton, and venison are occasionally served as delicacies. The meat of such animals as oxen, donkeys, elephants, horses, pigs, dogs, foxes, wolves, lions, monkeys, and apes is not to be eaten, as a rule. Those who eat the meat of such animals are despised and detested by the general public and the offenders are expelled to the outskirts of the city; they rarely show themselves among the people.

As regards different spirits and sweet wines of diverse tastes, drinks made from grapes and sugarcane are for the ksatriyas and fermented spirits and unfiltered wines are for the vaisyas to drink. The sramanas and brahmans drink grape and sugarcane juice, as they refrain from taking alcoholic beverages. For the low and mixed castes there are no specific drinks.

As to household implements, there are different articles made of various materials for various purposes. Miscellaneous necessities are always sufficiently at hand. Although cauldrons and big pots are used for cooking the rice steamer is unknown. Cooking utensils are mostly made of earthenware, with a few made of brass. When taking a meal a person eats from one vessel in which all the ingredients are mixed together. He takes the food with his fingers, never using spoons or chopsticks; the aged and the sick use copper spoons for eating food.

Gold, silver, brass, white jade, and crystal are local products, which are amassed in large quantities. Precious substances and rare treasures of different descriptions, procured from overseas, are commodities for trading. For the exchange of goods, gold and silver coins, cowries, and small pearls are used as the media of exchange.

The territories and boundaries of India have been described above and different local conditions have been briefly related here. I have made only a rough statement of what is common in all the regions of the country in a generalized manner. As regards the particular political administrations and social customs of different regions, I shall explain them separately under the heading of each country, as follows.

The country of Lampa is over one thousand li in circuit, with the Snow Mountains at its back in the north and the Black Range on the other three sides. The capital city is more than ten li in circuit.

Several hundred years ago the royal family of this country ceased to exist and since then powerful families have competed with each other for superiority in the absence of a great monarch. It has recently become a dependency of Kapist.

The country produces non-glutinous rice and much sugarcane. There are many trees but little fruit. The climate is temperate; there is little frost and no snow. The country is a rich and happy land and the people are fond of singing and chanting, but they are timid and deceitful by nature. They cheat and do not respect one another. They are ugly and short in stature and are frivolous and impetuous in behavior. They mostly wear white cotton and are nicely dressed.

There are more than ten monasteries with a few monks, most of whom are students of the Mahayana teachings. There are several tens of deva temples with many heretics.

From here going southeast for over one hundred li, I crossed a high mountain and a large river and then arrived in the country of Nagarahara (in North India).

This country is over six hundred li from east to west and two hundred fifty or sixty li from south to north. It is surrounded by steep and dangerous precipices on all sides.

The capital city is more than twenty li in circuit. There is no sovereign king to rifle over the country and it belongs to KapisT as a vassal state. Grain and fruit are produced in abundance and the climate is moderately warm. The people are simple and honest, as well as courageous and valiant. They do not value wealth but esteem learning and they venerate the buddha-dharma, though a few have faith in heretical religions. There are many monasteries but few monks. All the stupas are deserted and in dilapidated condition. There are five deva temples with over a hundred heretics.

Two li to the east of the capital city there is a stupa built by King Asoka that is over three hundred feet high with piled-up stones, on which there are marvelous sculptures.

This was the place where [in a former life] Sakya Bodhisattva once met Dtpamkara Buddha and spread a piece of deerskin and his own hair to cover the muddy ground [for Dtpamkara to tread on], and received a prediction of buddhahood from him. Although it has passed through a kalpa of destruction the ancient trace remains intact. On fast days various kinds of flowers descend on the spot and multitudes of the common people vie with one another in making offerings [to the stupa].

In a monastery to the west of the stupa there are a few monks. Further to the south, a small stupa marks the spot where the Bodhisattva covered up the muddy ground in a former life. It was erected by King Asoka at a secluded place to avoid the highway.

Inside the capital city there are the old foundations of a great stupa. I heard the local people say that it had formerly contained a tooth relic of the Buddha and that it was originally a tall and magnificent structure. Now there is no more tooth relic and only the old foundations remain there. Beside them there is a stupa more than thirty feet high

whose origin is unknown, according to local tradition. The people said that it dropped down from the air and took root at the spot. It was not built by human beings and it manifested many spiritual signs.

Over ten li to the southwest of the capital city there is a stupa that marks the spot where the Tathagata once alighted during his flight from Central India on his travels to seek edification. Moved by the event, the people of the country built the base of this spiritual stupa out of admiration. Not far away to the east there is a stupa marking the place where Sakya Bodhisattva met Dtpamkara Buddha in a former life and purchased some flowers [to offer to the buddha].

More than twenty li to the southwest of the capital city one reaches a small range of rocky hills where there is a monastery with lofty halls and multistoried pavilions, all constructed out of rocks. The buildings were all quiet and silent and not a single monk was to be found. Within the compound of the monastery there was a stupa more than two hundred feet high, built by King Asoka.

To the southwest of the monastery is a deep gully with overhanging rocks [on each side], from which water falls down the wall-like precipices. On the 879a rocky wall at the east precipice is a large cave that was the dwelling place of the naga Gopala. The entrance is small and narrow and it is dark inside the cave; water drips from the rocks down to the mountain path.

Formerly there was a shadowy image of the Buddha, resembling his true features with all the good physical marks, just as if he were alive. But in recent years it is not visible to everyone and even those who see it can only perceive an indistinct outline. Those who pray with utmost sincerity may get a spiritual response and see a clear picture, but only for a brief instant.

When the Tathagata was living in the world the naga was a cowherd whose duty was to supply the king with milk and cream. Once he failed to fulfill his task properly and was reprimanded by the king. With a feeling of hatred and malice, he purchased some flowers to offer to the stupa of prediction, in the hope that he might be reborn as an evil naga to devastate the country and do harm to the king. Then he went up to the rocky precipice and jumped down to kill himself. Thus he became a naga king and lived in this cave.

The moment he desired to go out of the cave to carry out his evil wishes, the Tathagata, with a mind of compassion for the people of the country, who would suffer havoc caused by the naga, arrived from Central India, flying through his supernatural power. At the sight of the Tathagata the naga’s malignant mind ceased. He accepted the ride of non-killing and wished to protect the right Dharma. So he requested that the Tathagata dwell in the cave permanently and [promised] to always offer alms to all his saintly disciples.

The Tathagata said to him, “I shall enter nirvana but I will leave my shadow behind for you, and I will send five arhats to always receive your offerings. Even when the right Dharma has disappeared into oblivion this arrangement will not be altered. If your malignant mind becomes agitated you should look at my shadow and, on account of your compassion and benevolence, your malignant mind will come to an end. During this bhadra- kalpa (“good eon”) all the future World-honored Ones will have compassion for you and leave their shadows behind.”

Outside the door of Shadow Cave there are two square rocks. On one of the rocks is the trace of the Tathagata’s footprint with the wheel sign dimly visible and it sometimes emits a light.

On either side of Shadow Cave there are many other caves, which are the places where the saintly disciples of the Tathagata used to sit in meditation. On a comer to the northwest of the Shadow Cave there is a stupa that marks the place where the Tathagata once took a walk. Beside it is another stupa, in which are stored the relics of the Tathagata’s hair and nail parings.

Not far from here another stupa marks the spot where the Tathagata preached on the true doctrine of the skandhas (five attributes of being), the ayatanas (twelve sense fields), and the dhatns (eighteen spheres, consisting of the six sense organs, the six sense objects, and the six consciousnesses).

To the west of Shadow Cave there is a large flat rock on which the Tathagata once washed his robe; the traces of the robe left on the rock are still dimly visible.

At more than thirty li to the southeast of the city one reaches the city of Hilo, which is four or five li in circuit; [its city wall] is high, precipitous, and impregnable. There are flowers, trees, and pools with pure water as bright as a mirror. The inhabitants of the city are simple and honest and they believe in the right Dharma. There is a multistoried pavilion with colorfully painted beams and pillars.

On the second story is a small stupa made of the seven precious substances, in which is preserved a piece of the Tathagata’s skull 879b bone, twelve inches in circumference with distinct hair pores, yellowish- white in color, which is contained in a precious casket that has been placed inside the stupa. Those who wish to tell their fortunes may prepare some fragrant plaster to make an impression of the skull bone and then read a clear written prediction according to the effects of their blessedness.

There is another small stupa made of the seven precious substances in which is stored the Tathagata’s cranial bone, which has the shape of a lotus leaf and is of the same color as the skull bone. It is also contained in a precious casket that has been sealed up and placed [in the stupa].

There is another small stupa made of the seven precious substances, in which is preserved an eyeball of the Tathagata, as large as a crabapple, brilliant and transparent throughout. It is also contained in a precious casket that has been sealed up and placed [in the stupa].

The Tathagata’s upper robe, made of fine cotton in a yellowish-red color, is placed in a precious casket. It has lasted a long time and is slightly damaged. The Tathagata’s pewter staff, with rings made of pewter and a sandalwood handle, is stored in a precious tube.

Recently a king heard that these relics belonged to the Tathagata and he captured them by force. After returning to his own country the king kept the relics in his palace but less than twelve days later the relics were lost. When he searched for them he found that they had returned to their original location.

These five holy objects have shown many spiritual signs. The king of Kapisi ordered five attendants to take care of the relics by offering incense and flowers, and worshipers came to pay reverence to them without cease. The attendants, wishing to spend their time in quietude and thinking that people would value money more than anything else, in order to stop the hubbub caused by visitors, made a rule to the effect that one gold coin would be charged to see the skull bone and five gold coins would be charged for making an impression. This ride was also applicable in different grades to the other relics. Even with these steep fees the number of worshipers increased.

To the northwest of the storied pavilion there is a stupa that is also very lofty and has shown many marvelous signs. When it is touched with a finger it shakes down to the basement and its bells ring harmoniously.

From here going toward the southeast among mountains and valleys for over five hundred li, I reached the country of Gandhara (at former times incorrectly transcribed as Qiantuowei, in the domain of North India).

The country of Gandhara is more than one thousand li from east to west and over eight hundred li from south to north, with the Indus on the east. The capital city, called Purusapura, is more than forty li in circuit. The royal family is extinct and the country is now under the domination of Kapisi. The towns and villages are desolate and have few inhabitants. In one comer of the palace city there are over one thousand families.

They produce abundant cereals and have flowers and fruit in profusion. The country grows much sugarcane and produces sugar candy. The climate is mild and there is scarcely any frost or snow.

The people are shy and timid by nature and are fond of literature and the arts. Most of them respect heretical religions; only a few believe in the right Dharma.

Since ancient times masters who wrote commentaries and theoretical treatises in India, such as Narayanadeva, Asafiga, Vasubandhu, Dharmatrata, Manoratha, Parsva, and so on, have been born in this country.

There were more than a thousand monasteries but they are now dilapidated and deserted, in desolate condition. Most of the stupas are also in rains. There are about a hundred deva temples inhabited by various heretics.

To the northeast inside the royal city there are the remains of the foundation of a precious terrace on which the Buddha’s almsbowl was once placed. After the Tathagata’s demise the bowl was brought to this country, where it was venerated with formal rituals for several hundred years, and then it was brought to various countries. It is now in Persia.

At a distance of eight or nine li to the southeast outside the city, there is a pipal tree more than one hundred feet tall with profuse branches and leaves that cast a dense shade on the ground. The four past buddhas sat under this tree and now statues of the four buddhas are still to be seen there. The remaining nine hundred and ninety-six buddhas of the bhadrakalpa will also sit under it,

divinely guarded and protected by gods and deities. Once, when Sakya Tathagata was sitting under this tree, facing south, he told Ananda, “Four hundred years after my demise there will be a king named Kaniska, who will erect a stupa not far south of here. Most of my bodily remains will be collected in it.”

To the south of the pipal tree there is a stupa constructed by King Kaniska.

In the four hundredth year after the Tathagata’s demise King Kaniska ascended the throne and ruled over Jambudvipa. He did not [originally] believe in the theory of retribution for good and evil deeds and contemptuously defamed the buddha-dharma. Once he was hunting in a marsh when a white hare appeared. The king chased after the hare and it suddenly disappeared at this place. In the woods he saw a young cowherd building a small stupa three feet high. The king asked the boy, “What are you doing?”

The boy replied, “Formerly Sakya Buddha made a wise prediction: A king will build a stupa at this auspicious place and most of my bodily remains will be collected in it.’ Your Majesty’s holy virtues were cultivated in your previous lives and your name coincides with the one mentioned in the prediction. Your divine merits and superior blessedness will be realized at this time. Thus I am here as a preliminary sign to remind you of the prediction.” With these words, the cowherd vanished.

Upon hearing these words the king was overjoyed and was proud to know that his name had been predicted by the Great Sage in his prophecy. Thereafter he professed the right faith and deeply believed in the buddha-dharma. Around the small stupa he built a stone stupa, wishing to encompass the smaller one, through the power of his merit. But no matter how tall he built the stone stupa the smaller one was always three feet higher, until the larger stupa reached over four hundred feet in height, standing on a base one and a half li in circuit, 880a with five flights of steps leading up to a height of one hundred fifty feet, so that it then covered the small stupa.

Delighted, the king also had gilded copper disks arranged in twenty-five tiers on the top. Then he placed one hu (hectoliter) of the Tathagata’s relic bones in the stupa, to which he piously made offerings.

When construction of the large stupa had just been completed the king saw that the small stupa was protruding, with half of its structure sideways at the southeast comer of the base [of the great stupa]. Enraged, the king threw the smaller stupa upward and it stayed there, half of it appearing in the stone base under the second flight of steps of the stupa, but another small stupa emerged at the original place. The king then gave up and remarked with a sigh, “Human affairs are bewildering but the merits of deities are insuppressible. What is the use of being angry with it, if it is supported by the gods?” Ashamed and fearful, the king apologized and returned home.

These two stupas still stand. Those who are ill and wish to pray for recovery offer incense and flowers to the stupas with pious minds, and in most cases they are cured.

On the southern side of the flight of steps at the east of the great stupa there are two carved stupas, one three and the other five feet high, in the same style and shape as the great stupa.

There are also two carved images of the Buddha, one four and the other six feet in height, resembling the Buddha sitting cross-legged under the bodhi tree. In the sunshine these images are of a dazzling golden color, and when they are gradually covered by shade the lines on the stone become bluish-violet in color.

Some local old people said that several hundred years ago there were golden-colored ants in the crevice of the stone; the big ones were the size of a fingernail and the small ones were the size of a grain of wheat. Following one another, they gnawed at the surface of the stone and the lines they made on the stone looked like incised grooves that were filled with golden sand to delineate the images, which are still in existence.

On the south side of the flight of steps leading up to the great stupa there is a painting of the Buddha sixteen feet in height, with two busts above the chest but only one body below it.

Some old people said that there was formerly a poor man who sustained himself by working as a laborer. Once he earned a gold coin and wished to make an image of the Buddha. He came to the stupa and said to a painter, “I wish to make a portrait of the Tathagata’s excellent features but I have only one gold coin, which is really insufficient for remuneration. This has been my long-cherished desire but I am poor and lack money.” In consideration of the poor man’s sincerity, the painter did not argue about the payment and promised to accomplish the job. Another man under the same circumstances came with a gold coin to request the painter to draw a portrait of the Buddha. Thus the painter accepted the money from both men and he asked another skillful painter to work together with him in drawing a single portrait.

When the two men came on the same day to worship the Buddha, the two painters showed them the portrait, pointing at it and saying, “This is the portrait you ordered.” The two men looked at each other, bewildered. The painters realized that they were doubtful about 880b the matter and said to them, “Why are you pondering the matter for so long? Whatever object we undertake to produce is done without the slightest fault. If our words are not false the portrait will show miracles.” As soon as they had uttered these words the portrait manifested a wonder: the body split into two busts, while the shadows intermingled into one, with the features shining brilliantly. The two men were happily convinced and delightedly fostered faith.

More than a hundred paces to the southwest of the great stupa there is a standing image of the Buddha made of white stone, eighteen feet high, facing north. It often worked miracles and frequently emitted light.

Sometimes people see it walking at night and circumambulating the great stupa. Recently a band of robbers intended to enter the stupa to steal the contents. The image came out to meet the robbers head-on and the robbers withdrew in fear. Then the image returned to its original place and stood there as usual. Thereafter the robbers corrected their error and made a fresh start in life. They walked about in towns and villages and related the event to all people, far and near.

At the left and right sides of the great stupa there are hundreds of small stupas, arranged as closely together as the scales of a fish. The Buddha’s images are magnificent, having been made with perfect craftsmanship. Unusual fragrances and strange sounds are sometimes perceived and spirits and genies, as well as holy ones, may be seen circumambulating the great stupa.

The Tathagata predicted that when this stupa has burned down and been rebuilt seven times, the buddha-dharma will come to an end. Previous sages have recorded that it has been destroyed and reconstructed three times. When I first came to this country the stupa had just suffered the disaster of conflagration. It is now under repair and the structure is not yet completed.

To the west of the great stupa there is an old monastery built by King Kaniska. The multistoried pavilion and the houses built on terraces were constructed so that eminent monks could be invited in recognition of their distinguished merits. Although the buildings are dilapidated they can still be regarded as wonderful constructions. There are a few monks who study the Hinayana teachings.

Since the monastery was constructed it has produced extraordinary personages from time to time, who were either writers of treatises or people who realized sainthood. The influence of their pure conduct and perfect virtue is still functioning.

On the third story of the pavilion is the room used by Venerable Parsva (“Ribs”). It has been in ruins for a long time but its location is indicated with a mark.

The venerable monk was a brahmanical teacher but he became a Buddhist monk at the age of eighty. Some young people in the city sneered at him, saying, “You stupid old man, why are you so ignorant? A Buddhist monk has two duties: first to practice meditation and second to recite scriptures. Now you are getting old and feeble and cannot make any more progress. So you are trying to pass yourself off as a monk among the pure mendicants but you do nothing but eat your fill.”

Having heard this reproach, Venerable Parsva apologized to the people and made a vow, saying, “If I do not thoroughly master the teachings of the Tripitaka and do not cut off all desires of the three realms of the world, so as to realize the six supernatural powers and possess the eight emancipations, I shall not lie down to sleep with my ribs touching the mat.”

He then worked hard and always meditated whether he was walking, sitting, or standing still. In the daytime he studied theories and doctrines and at night he sat quietly in meditation with a concentrated mind. In three years’ time he completely mastered the Tripitaka, cut off the desires of the three realms of the world, and obtained the wisdom of the three knowledges. As the people respected him, they called him Venerable Ribs (Parsva).

To the east of Venerable Parsva’s chamber there is an old room in which Vasubandhu Bodhisattva composed the Abhidharmakosa-sastra. Out of respect for him the people had the room sealed and indicated by a mark.

On the second story of the pavilion, at a place more than fifty paces to the south of Vasubandhu Bodhisattva’s room, is the place where the sastra master Manoratha (“As You Wish”) composed the Vibhasd-sastra.

The sastra master was born a thousand years after the nirvana of the Buddha. When he was young he loved learning and was eloquent in speech. His fame spread far and both clerics and laypeople had faith in him. At that time the influence of King Vikramaditya (“Valor Sun”) of Sravasti reached far and he brought the various parts of India under his domination. Every day he distributed five lakhs of gold coins as alms to paupers, orphans, and the solitary. The state treasurer, fearing that the national treasury would be exhausted, ironically remonstrated with the king, saying, “Your Majesty’s strong influence extends to various peoples and your kindness benefits even insects. Pray spend five more lakhs of gold coins to relieve the poor and needy of the four quarters. When the treasury is exhausted we can levy more taxes and repeated taxation will arouse the people’s resentment and grievance everywhere, but the monarch above may show off his kindness in bestowing charity upon the people and we subjects below will bear the blame of being disrespectful.”

The king said, “We collect surplus money to give to those who are short of it, it is not for ourselves that we squander the national wealth.” Thus five lakhs of gold coins were added to the sum of money given to the poor and needy.

Later, while out hunting, the king lost the trace of a wild boar and a man who found the animal was granted a reward of one lakh of gold coins. Now when the sastra master Manoratha once had his hair shaved, he paid the barber one lakh of gold coins and the state annalist accordingly put the event on record. The king was ashamed to have been surpassed by a monk in lavishing money and intended to insult the sastra master Manoratha in public. Thus he summoned a hundred heretical teachers of high virtue and deep learning, to whom he issued an order, saying,

“We wish to glean various views to find out the truth but different schools have different theories, so we do not know where to fix our mind. Now we wish to see which of your schools is superior and which is inferior, so that we may know which way we should follow exclusively.”

At the time the discussion was held the king issued another order, saying, “These heretical sastra masters are brilliant and talented scholars and the sra- manas of the Dharma should master their own theories well. If they win in the debate we shall venerate the buddha-dharma; otherwise we will slaughter the Buddhist monks.”

Then Manoratha debated with the heretics and defeated ninety-nine of the opponents, who fled in retreat. He slighted the last antagonist with contempt and talked with him fluently. When he came to the subject of fire and smoke, the king and the heretic said aloud, “The sastra master Manoratha has made a faulty statement. It is common sense that smoke precedes fire.”

Although Manoratha wished to explain his viewpoint no one would listen to his argumentation.

Ashamed of being insulted in public, he bit off his tongue and wrote a letter to his disciple Vasubandhu, saying, “Among groups supported by factions one cannot hold a great principle in competition, and in an assembly of ignorant people there is no way to argue for the right theory.” He died after having written these words.

Not long afterward, King Vikramaditya lost his kingdom and was succeeded by another king who adored and respected people of eminence and wisdom. Wishing to rehabilitate his teacher’s good name, Vasubandhu Bodhisattva came to the new king and said to him, “Your Majesty rules the kingdom with your saintly virtues and you render support to all living beings. My late teacher Manoratha was learned in abstruse and profound theories but the previous king held a grudge against him and besmirched his good name in public. As I have studied under his instruction I wish to avenge the wrong done to my teacher.”

The king, knowing that Manoratha had been a wise man and appreciating Vasubandhu’s upright character, summoned all the heretics who had debated with Manoratha to a meeting. Vasubandhu then reiterated what his teacher had expounded and all the heretics were defeated and withdrew.

Going to the northeast for more than fifty li from the monastery built by King Kaniska, I crossed a large river and reached the city of Puskaravati, which is fourteen or fifteen li in circuit. It is well populated and the lanes and alleys are connected with each other. Outside the west gate of the city there is a deva temple, in which the deva image is austere in appearance and often works miracles.

To the east of the city there is a stupa built by King Asoka. It marks the place where the four past buddhas preached the Dharma. Ancient saints and sages coming from Central India to subdue divine beings and teach human mortals at this place were very numerous. It was at this site that the sastra master Vasumitra (Shiyou in Chinese, formerly transcribed erroneously as Hexumiduo) composed the Abhidharma- prakarana-pdda-sdstra.

Four or five li to the north of the city there is an old monastery whose buildings are in desolation, with a few resident monks who are followers of Hinayana teachings. This is the place where the sastra master Dharmatrata (known as Fajiu in Chinese and erroneously transcribed as Damoduoluo in olden times) composed the Abhidharmatdbhidharma-hrdaya-sdstra.

Beside the monastery there is a stupa several hundred feet high built by King Asoka. The wood carvings and stone sculptures are quite different from work done by human artisans. Formerly, when Sakya Buddha was a king, he practiced the way of the bodhisattva at this place and gave alms tirelessly to all living beings according to their wishes. He was the king of this land for one thousand lives, and it was at this auspicious place where he surrendered his eyes in one thousand lives.

Not far east of where Sakya Buddha forsook his eyes there are two stone stupas, both more than one hundred feet high. The one on the right was erected by Brahma and the one on the left by Indra, and both are beautifully decorated with wonderful jewels and gems. After the demise of the Tathagata the gems turned into stone. Although the foundations have sunk the stupas still stand high and lofty.

More than fifty li to the northwest of the stupas built by Brahma and Indra 881b there is a stupa that marks the place where Sakya Tathagata converted the goddess Hariti to prevent her from doing harm to people. Thus it became the custom of the country to pray to the goddess for offspring.

More than fifty li to the north of the place where Hariti was converted, there is a stupa built at the spot where Syamaka Bodhisattva (formerly transcribed incorrectly as Shanmo Bodhisattva) gathered fruit to offer to his blind parents in fulfillment of his filial duty, and he met the king who was hunting and who accidentally hit him with a poisoned arrow. Indra, moved by Syamaka’s mind of sincerity, dressed the wound with medicine and his virtuous deed inspired the gods, who restored him to life very quickly.

Going to the southeast for more than two hundred li from the place where Syamaka Bodhisattva was injured, I reached the city of Varsa. To the north of the city there is a stupa built at the place where Prince Sudana (“Good Tooth”) said farewell to his countrymen at the city gate when he was banished from the city, and apologized to the people for having given his father’s elephant as a gift to a brahman. In the monastery beside the stupa there are more than fifty monks, all of whom are followers of the Hinayana teachings. It was at this place that the sastra master Isvara (“Self-existence”) composed the Abhidharmadipa-sastra.

Outside the east gate of Varsa there is a monastery with more than fifty monks, all of whom are followers of the Mahayana teachings. There is a stupa built by King Asoka. Formerly, when Prince Sudana was living in exile at Dandaloka Mountain (formerly known as Tante Mountain erroneously), a brahman begged for his sons and wife and then sold them at this place.

At a place more than twenty li to the northeast from Varsa one reaches Dandaloka Mountain. On the ridge there is a stupa built by King Asoka to mark the place where Prince Sudana once lived in seclusion. Not far away there is another stupa, built at the spot where the prince gave away his sons and wife to a brahman. The brahman beat the prince’s sons and wife until their blood ran to the ground and stained the earth. Even now the grass and plants still retain a reddish hue. The cave on the cliff was the place where the prince and his wife practiced meditation. The branches of the trees in the valley droop like curtains, and the prince used to roam about here. Nearby is a stone hermitage that was the abode of an ancient rsi (sagely anchorite).

At more than one hundred li to the northwest from the hermitage one crosses over a small hill and arrives at a large mountain. On the south of the mountain there is a monastery, in which lived a few monks who studied Mahayana teachings. The stupa beside it was built by King Asoka at the place where the rsi Unicom once lived. This rsi was ensnared by a lustful woman and lost his supernatural powers. The lustful woman then rode on his shoulders and returned to the city.

At more than fifty li to the northeast from Varsa one reaches a lofty mountain, on which there is a bluish stone image of Bhimadevi, wife of Mahesvara. The local people said that this image of the goddess existed naturally. It showed many marvels and many people came to give prayers. In all parts of India people, both noble and common, who wish to pray for blessedness flock to this place from far and near. Those who wish to see the physical form of the goddess may get a vision of her after fasting for seven days with a sincere and concentrated mind, and in most cases their wishes will be fulfilled.

At the foot of the mountain there is a temple for Mahesvara in which the ash-smearing heretics perform ceremonies.

Going for a hundred fifty li to the southeast from the Bhimadevi temple I reached the city of Udakhand, which is more than twenty li in circuit, bordering the Indus River in the south. The inhabitants are rich and happy. Precious goods pile up high and most of the rare and valuable things of different places are collected here.

Going for more than twenty li to the northwest from Udakhand I reached the city of Salatura, the birthplace of the rsi Panini, author of the Sabda-vidya-sastra.

At the beginning of antiquity the written language was rich and extensive in vocabulary, but with the passage of the kalpa of destruction the world became empty, and afterward the long-lived deities descended to the earth to guide human beings. Thereafter, literary documents were produced, and thence forth the source of literature became a torrential flood. Brahma and Indra wrote model compositions as the time required, and the rsis of each of the heretical systems formed their own words. The people studied what was taught by their predecessors and emulated what was handed down; but the efforts of the students were wasted because it was difficult for them to master everything in detail.

At the time when the human life span was a hundred years, the rsi Panini was born with innate knowledge of wide scope. Feeling pity at the shallowness of learning in his time, and wishing to expunge what was superficial and false and delete what was superfluous, he traveled about to make inquiries into the way of learning. He met with Mahesvara and told the deity of his intention. Mahesvara said, “How grand it is! I shall render you assistance.” The rsi withdrew after hearing these words and concentrated his mind to ponder the matter. He collected all words and composed a text of one thousand stanzas, each stanza consisting of thirty-two syllables. In this book he made a thorough study of the written and spoken language of both ancient and modem times, and offered it to the king in a sealed envelope.

The king treasured it very much and ordered that all the people of the country should learn the text; one who could recite it fluently by heart would be rewarded with a thousand gold coins. Thus this text was transmitted from teacher to pupil and became prevalent at that time. Henceforth the brahmans in this city are great scholars of high talent with knowledge of wide scope.

In the city of Salatura there is a stupa built at the place where an arhat converted a disciple of Panini.

Five hundred years after the demise of the Tathagata a great arhat came from Kasmira to this place in the course of his journey. When he saw a brahman teacher beating a schoolboy, he asked the brahman, “Why are you chastising the child?”

The brahman said, “I asked him to learn the Sabdcividya-sastra but he has not made progress with the passage of time.”

The arhat smiled amiably and the old brahman said, “A sramana should be compassionate and have sympathy for all living beings. But you are now smiling and I would like to know why.”

The arhat said in reply, “It is not easy for me to tell you, for fear that it might cause you deep doubt. Have you ever heard about the rsi Panini, who composed the Sabda-vidya-sastra for the instruction of posterity?”

The brahman said, “He was a scion of this city. Out of admiration for his virtue his disciples have made an image of him, which is still in existence.”

The arhat said, “This son of yours is [a reincarnation of] that rsi. On account of his rich knowledge he took delight in studying worldly books, discussing only the heretical theories and never researching the truth. He wasted his spirit and wisdom and is still involved in the wheel of rebirth. By virtue of his surplus good deeds he has been reborn as your beloved son. But he simply wasted his energy studying the diction and language of worldly books How can this be the same as the Tathagata’s holy teachings, which give rise to bliss and wisdom in a mysterious way?

“In olden times there was a decayed tree by the shore of the South Sea, and five hundred bats lived in the holes of the tree. Once a caravan of merchants stayed under the tree. As the season was windy and chilly and the merchants were hungry and cold, they piled up firewood and built a fire under the tree. The smoke and flames gradually began to bum fiercely and set the decayed tree on fire. One of the merchants recited the Abhidharma pitaka after midnight, and the bats, even though scorched by the heat, so loved to listen to the recitation of the Dharma that they would not leave the place; they disregarded the intense heat and died in the tree. According to their karmic force they were reborn as human beings and renounced their homes to learn and practice [the Buddhist teachings]. As they had heard the recitation of the Dharma they were clever and intelligent and realized sainthood; thus they became fields of blessedness for the world.

“Recently King Kaniska and Venerable Parsva summoned five hundred holy persons in Kasmfra to compile the Vibhasa-sastra, and these five hundred holy persons are the five hundred bats that lived in that decayed tree.

Although I am an unworthy person I was one of them. From this we may see that there is such a great difference between the superior and the inferior, the virtuous and the vicious, as that between those that fly high in the air and those that crouch down on the ground. Permit your beloved son to become a monk, for the merits of becoming a monk are indescribable in words.”

After having spoken these words the arhat performed miracles and disappeared all of a sudden.

The brahman cherished a deep feeling of awe and faith and exclaimed sadhu (“excellent”) for a long time. He related everything to the people of the neighborhood and permitted his son to become a monk to learn and practice [the Buddhist teachings]. He then gained faith and honored the Triple Gem, and his countrymen have accepted his edification with more and more earnestness up to this day.

Going from Udakhand to the north over mountains and across rivers for more than six hundred li, I reached the country of Udyana. (This means “park,” as it was a pleasure garden of a previous wheel king. Formerly it was transcribed as Wuchang or Wutu, both erroneously. It is in the domain of North India.)

End of Fascicle II of The Great Tang Dynasty

Record of the Western Regions

MUA THỈNH KINH SÁCH PHẬT HỌC

DO NXB LIÊN PHẬT HỘI PHÁT HÀNH

Mua sách qua Amazon sẽ được gửi đến tận nhà - trên toàn nước Mỹ, Canada, Âu châu và Úc châu.

Quý vị đang truy cập từ IP 216.73.216.157 và chưa ghi danh hoặc đăng nhập trên máy tính này. Nếu là thành viên, quý vị chỉ cần đăng nhập một lần duy nhất trên thiết bị truy cập, bằng email và mật khẩu đã chọn.

Chúng tôi khuyến khích việc ghi danh thành viên ,để thuận tiện trong việc chia sẻ thông tin, chia sẻ kinh nghiệm sống giữa các thành viên, đồng thời quý vị cũng sẽ nhận được sự hỗ trợ kỹ thuật từ Ban Quản Trị trong quá trình sử dụng website này.

Việc ghi danh là hoàn toàn miễn phí và tự nguyện.

Ghi danh hoặc đăng nhập

... ...

Trang chủ

Trang chủ