Mất tiền không đáng gọi là mất; mất danh dự là mất một phần đời; chỉ có mất niềm tin là mất hết tất cả.Ngạn ngữ Nga

Nếu tiền bạc không được dùng để phục vụ cho bạn, nó sẽ trở thành ông chủ. Những kẻ tham lam không sở hữu tài sản, vì có thể nói là tài sản sở hữu họ. (If money be not thy servant, it will be thy master. The covetous man cannot so properly be said to possess wealth, as that may be said to possess him. )Francis Bacon

Hãy đặt hết tâm ý vào ngay cả những việc làm nhỏ nhặt nhất của bạn. Đó là bí quyết để thành công. (Put your heart, mind, and soul into even your smallest acts. This is the secret of success.)Swami Sivananda

Mục đích của cuộc sống là sống có mục đích.Sưu tầm

Giặc phiền não thường luôn rình rập giết hại người, độc hại hơn kẻ oán thù. Sao còn ham ngủ mà chẳng chịu tỉnh thức?Kinh Lời dạy cuối cùng

Yêu thương và từ bi là thiết yếu chứ không phải những điều xa xỉ. Không có những phẩm tính này thì nhân loại không thể nào tồn tại. (Love and compassion are necessities, not luxuries. Without them humanity cannot survive.)Đức Đạt-lai Lạt-ma XIV

Hạnh phúc giống như một nụ hôn. Bạn phải chia sẻ với một ai đó mới có thể tận hưởng được nó. (Happiness is like a kiss. You must share it to enjoy it.)Bernard Meltzer

Cỏ làm hại ruộng vườn, si làm hại người đời. Bố thí người ly si, do vậy được quả lớn.Kinh Pháp Cú (Kệ số 358)

Phán đoán chính xác có được từ kinh nghiệm, nhưng kinh nghiệm thường có được từ phán đoán sai lầm. (Good judgment comes from experience, and often experience comes from bad judgment. )Rita Mae Brown

Nếu bạn không thích một sự việc, hãy thay đổi nó; nếu không thể thay đổi sự việc, hãy thay đổi cách nghĩ của bạn về nó. (If you don’t like something change it; if you can’t change it, change the way you think about it. )Mary Engelbreit

Nếu muốn người khác được hạnh phúc, hãy thực tập từ bi. Nếu muốn chính mình được hạnh phúc, hãy thực tập từ bi.Đức Đạt-lai Lạt-ma XIV

Trang chủ »» Danh mục »» TỦ SÁCH RỘNG MỞ TÂM HỒN »» The Art of Living »» INTRODUCTION »»

The Art of Living

»» INTRODUCTION

Xem Mục lục

Xem Mục lục  Vietnamese || Đối chiếu song ngữ

Vietnamese || Đối chiếu song ngữ

- none

- »» INTRODUCTION

- Chapter 1. THE SEARCH

- Chapter 2. THE STARTING POINT

- Chapter 3. THE IMMEDIATE CAUSE

- Chapter 4. THE ROOT OF THE PROBLEM

- Chapter 5. THE TRAINING OF MORAL CONDUCT

- Chapter 6. THE TRAINING OF CONCENTRATION

- Chapter 7. THE TRAINING OF WISDOM

- Chapter 8. AWARENESS AND EQUANIMITY

- Chapter 9. THE GOAL

- Chapter 10. THE ART OF LIVING

- Appendix A. THE IMPORTANCE OF VEDANĀ IN THE TEACHING OF THE BUDDHA

- Appendix B. PASSAGE ON VEDANĀ FROM THE SUTTAS

Suppose you had simply heard that such an opportunity existed, and that people like yourself were not only willing but eager to spend their free time in this way. How would you describe their activity? Navel-gazing, you might say, or contemplation; escapism or spiritual retreat; self-intoxication or self-searching; introversion or introspection. Whether the connotation is negative or positive, the common impression of meditation is that it is a withdrawal from the world. Of course there are techniques that function in this way. But meditation need not be an escape. It can also be a means to encounter the world in order to understand it and ourselves.

Every human being is conditioned to assume that the real world is outside, that the way to live life is by contact with an external reality, by seeking input, physical and mental, from without. Most of us have never considered severing outward contacts in order to see what happens inside. The idea of doing so probably sounds like choosing to spend hours staring at the test pattern on a television screen. We would rather explore the far side of the moon or the bottom of the ocean than the hidden depths within ourselves.

But in fact the universe exists for each of us only when we experience it with body and mind. It is never elsewhere, it is always here and now. By exploring the here-and-now of ourselves we can explore the world. Unless we investigate the world within we can never know reality—we will only know our beliefs about it, or our intellectual conceptions of it. By observing ourselves, however, we can come to know reality directly and can learn to deal with it in a positive, creative way.

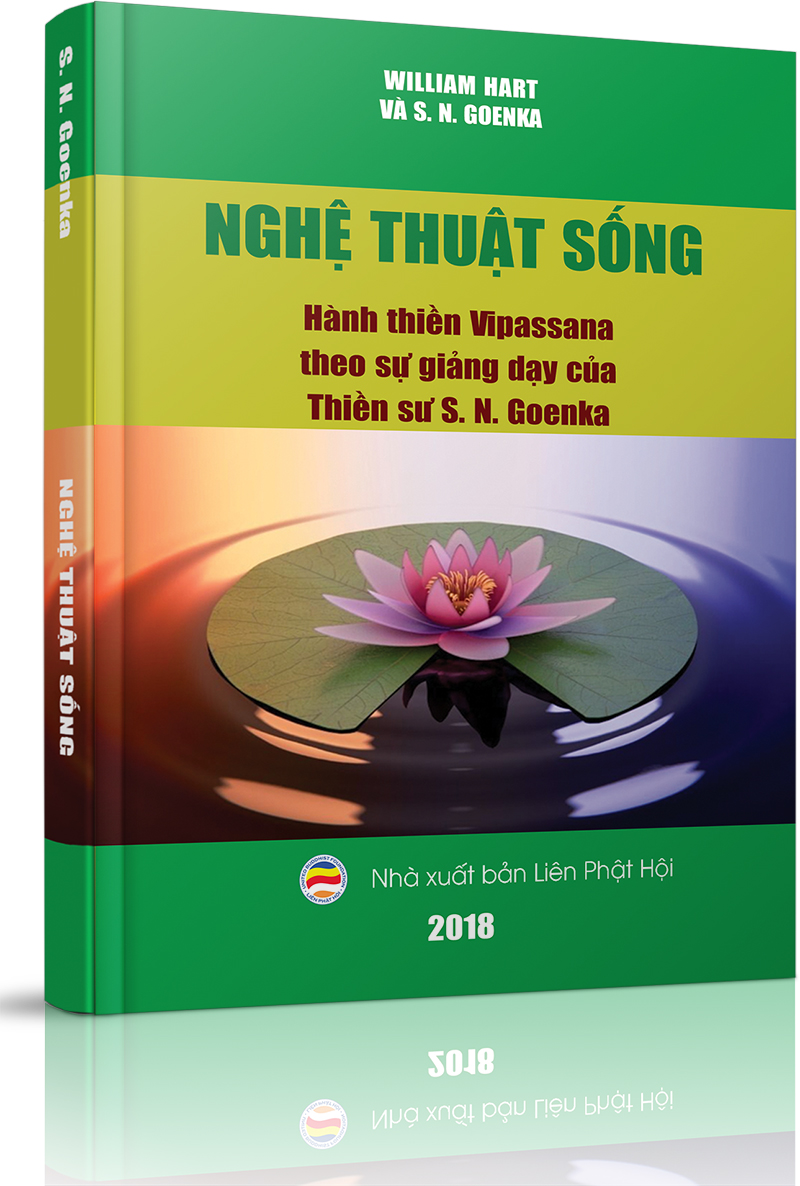

One method of exploring the inner world is Vipassana meditation as taught by S. N. Goenka. This is a practical way to examine the reality of one's own body and mind, to uncover and solve whatever problems lie hidden there, to develop unused potential, and to channel it for one's own good and the good of others.

Vipassanā means “insight” in the ancient Pāli language of India. It is the essence of the teaching of the Buddha, the actual experience of the truths of which he spoke. The Buddha himself attained that experience by the practice of meditation, and therefore meditation is what he primarily taught. His words are records of his experiences in meditation, as well as detailed instructions on how to practice in order to reach the goal he had attained, the experience of truth.

This much is widely accepted, but the problem remains of how to understand and follow the instructions given by the Buddha. While his words have been preserved in texts of recognized authenticity, the interpretation of the Buddha’s meditation instructions is difficult without the context of a living practice.

But if a technique exists that has been maintained for unknown generations, that offers the very results described by the Buddha, and if it conforms precisely to his instructions and elucidates points in them that have long seemed obscure, then that technique is surely worth investigating. Vipassana is such a method. It is a technique extraordinary in its simplicity, its lack of all dogma, and above all in the results it offers.

Vipassana meditation is taught in courses of ten days, open to anyone who sincerely wishes to learn the technique and who is fit to do so physically and mentally. During the ten days, participants remain within the area of the course site, having no contact with the outside world. They refrain from reading and writing, and suspend any religious or other practices, working exactly according to the instructions given. For the entire period of the course they follow a basic code of morality which includes celibacy and abstention from all intoxicants. They also maintain silence among themselves for the first nine days of the course, although they are free to discuss meditation problems with the teacher and material problems with the management.

During the first three and a half days the participants practice an exercise of mental concentration. This is preparatory to the technique of Vipassana proper, which is introduced on the fourth day of the course. Further steps within the practice are introduced each day, so that by the end of the course the entire technique has been presented in outline. On the tenth day silence ends, and meditators make the transition back to a more extroverted way of life. The course concludes on the morning of the eleventh day.

The experience of ten days is likely to contain a number of surprises for the meditator. The first is that meditation is hard work! The popular idea that it is a kind of inactivity or relaxation is soon found to be a misconception. Continual application is needed to direct the mental processes consciously in a particular way. The instructions are to work with full effort yet without any tension, but until one learns how to do this, the exercise can be frustrating or even exhausting.

Another surprise is that, to begin with, the insights gained by self- observation are not likely to be all pleasant and blissful. Normally we are very selective in our view of ourselves. When we look into a mirror we are careful to strike the most flattering pose, the most pleasing expression. In the same way we each have a mental image of ourselves which emphasizes admirable qualities, minimizes defects, and omits some sides of our character altogether. We see the image that we wish to see, not the reality. But Vipassana meditation is a technique for observing reality from every angle. Instead of a carefully edited self-image, the meditator confronts the whole uncensored truth. Certain aspects of it are bound to be hard to accept.

At times it may seem that instead of finding inner peace one has found nothing but agitation by meditating. Everything about the course may seem unworkable, unacceptable: the heavy timetable, the facilities, the discipline, the instructions and advice of the teacher, the technique itself.

Another surprise, however, is that the difficulties pass away. At a certain point meditators learn to make effortless efforts, to maintain a relaxed alertness, a detached involvement. Instead of struggling, they become engrossed in the practice. Now inadequacies of the facilities seem unimportant, the discipline becomes a helpful support, the hours pass quickly, unnoticed. The mind becomes as calm as a mountain lake at dawn, perfectly mirroring its surroundings and at the same time revealing its depths to those who look more closely. When this clarity comes, every moment is full of affirmation, beauty, and peace.

Thus the meditator discovers that the technique actually works. Each step in turn may seem an enormous leap, and yet one finds one can do it. At the end of ten days it becomes clear how long a journey it has been from the beginning of the course. The meditator has undergone a process analogous to a surgical operation, to lancing a pus-filled wound. Cutting open the lesion and pressing on it to remove the pus is painful, but unless this is done the wound can never heal. Once the pus is removed, one is free of it and of the suffering it caused, and can regain full health. Similarly, by passing through a ten-day course, the meditator relieves the mind of some of its tensions, and enjoys greater mental health. The process of Vipassana has worked deep changes within, changes that persist after the end of the course. The meditator finds that whatever mental strength was gained during the course, whatever was learned, can be applied in daily life for one’s own benefit and for the good of others. Life becomes more harmonious, fruitful, and happy.

The technique taught by S. N. Goenka is that which he learned from his teacher, the late Sayagyi U Ba Khin of Burma, who was taught Vipassana by Saya U Thet, a well-known teacher of meditation in Burma in the first half of this century. In turn, Saya U Thet was a pupil of Ledi Sayadaw, a famous Burmese scholar-monk of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Further back there is no record of the names of the teachers of this technique, but it is believed by those who practise it that Ledi Sayadaw learned Vipassana meditation from traditional teachers who had preserved it through generations since ancient times, when the teaching of the Buddha was first introduced into Burma.

Certainly the technique agrees with the instructions of the Buddha on meditation, with the simplest, most literal meaning of his words. And most important, it provides results that are good, personal, tangible, and immediate.

This book is not a do-it-yourself manual for the practice of Vipassana meditation, and people who use it this way proceed entirely at their own risk. The technique should be learned only in a course where there is a proper environment to support the meditator and a properly trained guide. Meditation is a serious matter, especially the Vipassana technique, which deals with the depths of the mind. It should never be approached lightly or casually. If reading this book inspires you to try Vipassana, you can contact the addresses listed at the back to find out when and where courses are given.

The purpose here is merely to give an outline of the Vipassana method as it is taught by S. N. Goenka, in the hope that this will widen the understanding of the Buddha’s teachings and of the meditation technique that is their essence.

Swimology

Once a young professor was making a sea voyage. He was a highly educated man with a long tail of letters after his name, but he had little experience of life. In the crew of the ship on which he was travelling was an illiterate old sailor. Every evening the sailor would visit the cabin of the young professor to listen to him hold forth on many different subjects. He was very impressed with the learning of the young man.

One evening as the sailor was about to leave the cabin after several hours of conversation, the professor asked, “Old man, have you studied geology?”

“What is that, sir?”

“The science of the earth.”

“No, sir, I have never been to any school or college. I have never studied anything.”

“Old man, you have wasted a quarter of your life.”

With a long face the old sailor went away. “If such a learned person says so, certainly it must be true,” he thought. “I have wasted a quarter of my life!”

Next evening again as the sailor was about to leave the cabin, the professor asked him, “Old man, have you studied oceanography?”

“What is that, sir?”

“The science of the sea.”

“No, sir, I have never studied anything.”

“Old man, you have wasted half your life.”

With a still longer face the sailor went away: “I have wasted half my life; this learned man says so.”

Next evening once again the young professor questioned the old sailor: “Old man, have you studied meteorology?”

“What is that, sir? I have never even heard of it.”

“Why, the science of the wind, the rain, the weather.”

“No, sir. As I told you, I have never been to any school. I have never studied anything.”

“You have not studied the science of the earth on which you live; you have not studied the science of the sea on which you earn your livelihood; you have not studied the science of the weather which you encounter every day? Old man, you have wasted three quarters of your life.”

The old sailor was very unhappy: “This learned man says that I have wasted three quarters of my life! Certainly I must have wasted three quarters of my life.”

The next day it was the turn of the old sailor. He came running to the cabin of the young man and cried, “Professor sir, have you studied swimology?”

“Swimology? What do you mean?”

“Can you swim, sir?”

“No, I don't know how to swim.”

“Professor sir, you have wasted all your life! The ship has struck a rock and is sinking. Those who can swim may reach the nearby shore, but those who cannot swim will drown. I am so sorry, professor sir, you have surely lost your life.”

You may study all the “ologies” of the world, but if you do not learn swimology, all your studies are useless. You may read and write books on swimming, you may debate on its subtle theoretical aspects, but how will that help you if you refuse to enter the water yourself? You must learn how to swim.

MUA THỈNH KINH SÁCH PHẬT HỌC

DO NXB LIÊN PHẬT HỘI PHÁT HÀNH

Mua sách qua Amazon sẽ được gửi đến tận nhà - trên toàn nước Mỹ, Canada, Âu châu và Úc châu.

Quý vị đang truy cập từ IP 216.73.216.44, 147.243.245.55 và chưa ghi danh hoặc đăng nhập trên máy tính này. Nếu là thành viên, quý vị chỉ cần đăng nhập một lần duy nhất trên thiết bị truy cập, bằng email và mật khẩu đã chọn.

Chúng tôi khuyến khích việc ghi danh thành viên ,để thuận tiện trong việc chia sẻ thông tin, chia sẻ kinh nghiệm sống giữa các thành viên, đồng thời quý vị cũng sẽ nhận được sự hỗ trợ kỹ thuật từ Ban Quản Trị trong quá trình sử dụng website này.

Việc ghi danh là hoàn toàn miễn phí và tự nguyện.

Ghi danh hoặc đăng nhập

... ...

Trang chủ

Trang chủ